Using profit to repay debt, expand or invest off farm

Author: Bernie Munro (Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited) | Date: 07 Sep 2016

Take home messages

• Tax minimisation versus wealth creation (short term versus longer term strategies).• What form is the profit and when do you take it?

• Assets spread and liquidity.

• Regular and consistent discussion with everyone at the table.

Background

What is profit, how is it identified or measured and how do operations use this information to make proactive decisions are all questions business owners need to consider Typically profit, ‘the excess of income over expenditure’ can be held within a business in a number of forms; it may be cash, grain, livestock or capital gain in land. We typically see the relationship of cash profits leading to taxation being payable, but again this depends very heavily on the vehicle or type of entity within which you are doing business. Each operation is different by way of structure and each type of structure has their positive and negative attributes.

Many farming operations largely focus on the production which drives cash flow to cover costs and potentially arrive with a surplus. The challenge for many is to identify these potential surpluses early, in order to adequately plan and implement the strategy for its expenditure. Sadly for many operations, understanding the performance of the business is based upon the completion of BAS returns aligned to tax obligations.

It is interesting to hear farm business owners say ‘we are making money, but we have no cash’. Probably more disappointing is that when operators do stop to consider their planning, they are torn across multiple reports constructed for differing purposes and become frustrated. Even more concerning is farm businesses basing their actions on saving tax without a true and correct basis for this decision.

For consistency businesses should avail themselves of ‘management reports’ created solely for the purpose of understanding the cash flow outcomes as a result of normal trading. When this is reviewed on a monthly basis it can go a long way to increasing the owners’ awareness of the strength of their business.

Firstly it will provide a clearer picture when considering returns and profitability and also the impact of inventory sales or retention. For example, a lot of effort can be invested in holding inventory to minimize taxation only to impact the ultimate returns from the sale of these outputs. Additionally, many operations can get confused as they hold crop inventories and sales in or out of reporting periods which confuses decisions on a ‘year in, year out basis’.

Ideally the ‘balanced’ operation will consider their needs, which are highly driven by cash flow to identify the best use of surplus positions. Unfortunately, given the seasonality of farming operations and the realisation of cash flow across the year, many are squeezed into shorter term positions and long term strategic decisions are not the priority. For example, pre purchase of inputs (chemicals, fertiliser, repairs and maintenance and interest) to manage their tax is often a decision that is addressed. This can prove to be beneficial but they are short term in nature. I am not however surprised by the flurry of expenditure that occurs every year which is driven solely by the purpose of not realizing a profit and therefore not delivering a taxable income.

All businesses engage the services of professionals to assist them in the running of their business. The scope of this engagement however can vary greatly from shoebox accounting through to highly specific analysis and advice on every aspect of an operation’s function. The challenge for many businesses is how to utilise this advice to set strategies for the business across the short, medium and longer terms.

Whether the advice tabled is sought through your accountant, agricultural and or financial adviser or as a component of the discussions with your financier, the key is ensuring that it is timely in nature, contains sufficient detail regarding assumptions and analysis and is in line with the strategy of your business. The information is only one component of the process. Unless all of the advice providers are around the same table then the context of the advice they provide, may face competing priorities and be difficult to deliver in reality.

For example, personal decisions based on succession, retirement, wealth creation and or schooling may not in fact be practical or achievable when compared with the actual operations of a business. Issues relating to cash availability or equity of a farming operation often impact heavily on the actual ability to take, change or maintain any course of action. This is further compounded by the fact that many operations have the majority of their assets tied up in the farm by way of land, machinery and stock on hand. In these cases liquidity becomes a major issue as whilst assets abound, cash and cash flow are normally tight, stifling or inhibiting the ability to make decisions.

The key is to ensure that those involved in the business (owners) and those that advise the business are clear and inclusive on the advice they provide and they provide their advice with some awareness of the greater business goals. Importantly, this discussion between all those involved allows for planning to take place which considers the short term (3- 6 months) medium term (2-5yrs) and long term (10+ yrs) goals to be identified and documented. In completing this activity, communication takes place that enables clarity regarding decisions on profit to be taken which are more considered and allow for input on tax planning, asset diversification and liquidity whilst being tied to the personal needs of the operation. The ideal is to have consistent planning which is well communicated and reviewed.

If for example you expect to acquire the neighbouring property in three years then you need to consider whether this is a ‘reality’ when you consider your current or expected debt position. In the cycle of asset returns, is acquisition of property the most appropriate decision? Have you considered what is happening around you, in other businesses such as yours?

The average annual total farm return (operating and capital gain) for mixed farms in NSW over the last 25 years has been 9.01 per cent (Eves, 2014).

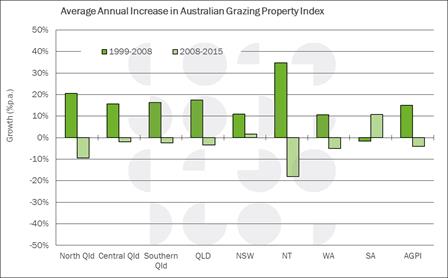

Farming assets have historically provided returns by way of capital gain and if we consider an index of Australian grazing properties prepared by Fuller (2016) on national property sales, the data exhibits compound growth of 4.7 per cent between the years 1980 to 2015. The danger in relying on these gains is the volatility that can be experienced across shorter terms. For example, if we consider movements in time bands 1980 – 1988 (+14.2%), 1988 – 1999 (-3.8%), 1999 – 2008 (+15.0%) and 2008 – 2015 (-4.0%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Average annual increase in Australian grazing property index during 1999-2008 (left hand column) and 2008-2015 (right hand column) time bands for different regions of Australia.

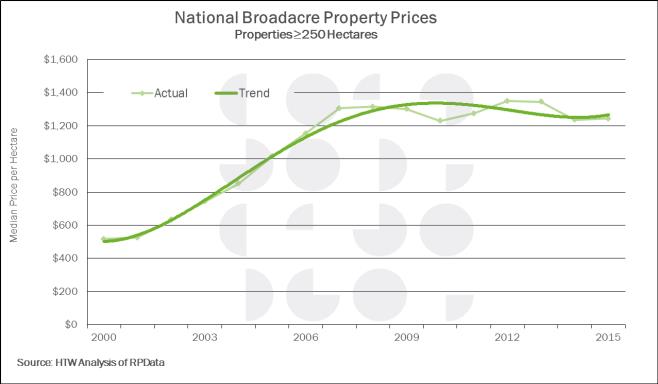

When considering broadacre property prices and trends, the growth on properties above 250ha has trended with less volatility when considered on a national basis (Figure 2).

Figure 2: National broadacre property prices ($/ha) for properties greater than 250 hectares from 2000-2015 (Source: HTW Analysis of RPData).

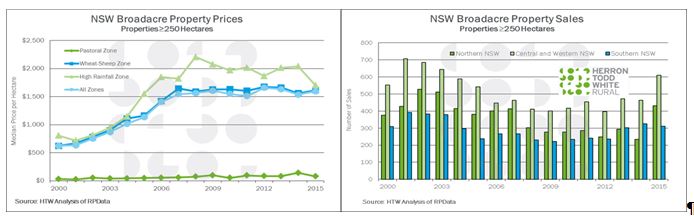

However, if we consider smaller regional trends the impact of supply and demand become more apparent. Sales last year (2015) increased by 34 per cent or an additional 236,000 hectares with all regions noting increased volumes. The NSW North West sales data did reduce in 2014 due to larger size of assets and lower $ per hectare (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Regional trends in property prices for NSW NorthWest (Source: HTW RPData).

Some comfort can be gained from the longer term trend that indicates an increase in landed asset values can be achieved. The purchase of additional farming country may be prudent but the most important consideration may well relate to liquidity of the asset if it is required to be sold. Similar principles apply to off farm investments. However, as has been evidenced from the commercial property market of recent times, asset volatility is the key. In the commercial property space, valuations are based upon tenancy and tenor or time of the lease that may be involved.

Asset growth is either funded by profit or debt. However, debt does form the basis of most acquisitions, leveraged off the existing farming asset. This can utilise existing equity or a ‘lazy balance sheet’ to increase assets but should be undertaken in a measured way.

The ability to fund debt from the market has been possible over the longer term and investors have been confident in taking position within the agribusiness space. The contrast has been a tightening in capital for utilisation within the commercial property segment of the marketplace, further complicated with an oversupply of commercial assets coming to the market with reduced or vacant tenancy.

The cost of this capital (debt) also has a considerable amount of volatility and is the focus of many conversations. Significant attention is directed towards interest rates and whether they are too high. I would prefer people to consider the return on the asset against the cost of the capital to own it.

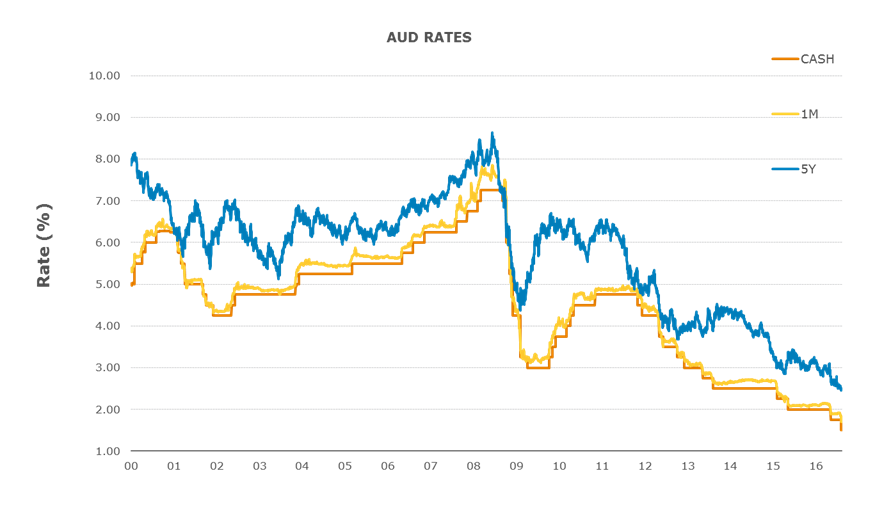

Figure 4: Interest rates (%) for the Australian market from 2000 to 2016 (Source: ANZ Treasury).

Figure 4 shows the base cost of funds from the commercial bill market from 2000 - 2016. Figure 4 does not take into account liquidity costs and risk margins that are associated with the actual cost of finance. The current market conditions are demonstrating historical ‘lows’ in terms of base costs. The average cost of funds (excluding liquidity and risk) between 2000 and 2016 for 90 day commercial bills (90d bank bill swap bid rate (BBSY)) is 4.69 per cent in comparison at the time of writing (1st September 2016) the 90d BBSY was 1.78 per cent. To put this into context, the current base funding cost is approximately 38% of the historical 16 year average.

I do see many businesses holding back in their decision to take fixed rate positions in the belief that interest rates will go lower. Future reductions may be seen, but waiting to see the bottom of the market is difficult because we only know the market has bottomed after the interest rates rise.

It is imperative that all businesses consider their cost of funds across their whole debt picture by identifying their ‘average cost’ of funding across all of their positions both fixed and variable. The prudent business will consider their funding by taking into consideration the tenor or term and may have multiple fixed positions to ensure that these tranches of debt do not mature into the market at the same time. Alignment of debt against multiple terms allows for some protection against market anomalies. This may look like variable, three or five year fixed terms. These terms allow for short term profit realization and debt payback, medium term funding which may allow for profits to enable payback following years three and four and core ongoing debt out five years, respectively. Do not be afraid to review your fixed rate positions across their terms to understand the potential benefits from breaking and resetting new positions to take advantage of market pricing and external pressures.

Conclusion

The information required to make effective decisions around ‘What to do with profit - repay debt, expand or invest off farm?’ is freely available and the people that can assist you with these decisions are plentiful.

The main challenge is having the providers of the inputs around the same table to ensure that the decision process is one that in reality can occur as the content and context of the information provided can have competing outcomes.

Unless you balance your personal needs with those of the business and have a plan which is consistently reviewed and reset, then in essence you may well be making decisions that are based on the short term or even worse on emotion.

Longer term strategies that are appropriately considered and which provide incremental wealth creation can have a very big impact on the ultimate outcome for retirement, succession or even liquidity. If we base our decisions on shorter terms in a reactionary sense, then we can increase the risks or volatility that we could encounter, which limits our ability to act.

Lastly, to hold a greater mix of investments both on and off farm can provide some flexibility and liquidity that can be utilised in times of changing personal circumstances. As the old saying goes ‘it pays not to hold all of your eggs in one basket’.

References and useful resources

Eves, Chris (2014). The Analysis of NSW Rural Property Investment Returns: 1990-2014. QLD University of Technology.

Fuller, Scott (2016) Presentation to NSW Farmers Association based on RP Data of property sales. Heron Todd White.

Farm Policy Journal Vol 13 No 2 Winter Quarter 2016 Australian Farm Institute – Understanding the Value of Agricultural Land

Contact details

Bernie Munro

Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited.

1/8 White Street Tamworth NSW 2340

0407171567

Bernard.munro@anz.com

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK