Background

There are many conflicting needs in a farm business, as with any business. Expenses such as chemicals, fertiliser, repairs, wages, new equipment, education costs and interest all exist. It is often a challenge to determine what to do with profits assuming they are available. Should we reduce our debt that has been increasing over the last 10 years due to bad seasons and prices? Should we purchase that new tractor that will make the business more efficient? Should we spend money before the end of June to ‘save’ tax? Or should we invest some money off-farm for our retirement which is a long way off, or to provide something for our children who decide they are not coming home to the farm, or to educate our children. Addressing these questions are some of the highest priority that a farm business owner can make, aside from production decisions.

The vast majority of Australian farm businesses have the majority of their capital tied up in land, plant and stock. This has been a sound investment strategy for many years, with capital gain on land being reasonable and operating returns, at least for the better producers, being comparable with other opportunities. However, this does not provide diversification when it comes to funds for a rainy day, in the case of droughts and floods, or to fund retirement and succession events.

By starting early and building off-farm wealth in a conservative and consistent fashion, farm businesses will be better placed to weather the ups and downs of our industry, retire independently of the business and better cater for the family members that decide to pursue other opportunities.

Discussion

We have seen the financial results of the ‘Local Farm’ and will use this as the basis of answering some key questions: what to do with profits, how to manage debt, the role of off-farm investment and the tax considerations of each of these decisions.

The example ‘Local Farm’ is profitable, which is a good starting point as not all farms are profitable. It has a moderate gearing level by today’s standards and would appear to be able to withstand some adverse seasons/prices without risking the entire business. We have assumed for the purpose of this exercise that the numbers provided are consistent over a long time frame (20 years) which is never the case, but allowing for good years and bad years, this is the average.

By way of quick education, tax is calculated on net profit after interest but before capital and personal expenditure (non deductible). I will not get into accounting lingo but this is important if we are playing with some of these numbers. The ‘Local Farm’ does have equipment finance payments of $150,000 per annum which are not normally fully deductible, but again for the purpose of this exercise we will assume they are, and that they remain consistent as the farmer upgrades machinery over time.

Different operating structures have different tax rates/treatments, but again we will keep this simple. A tax rate of 25 per cent has been applied in this case.

Tax minimisation is a process whereby an individual or a business legally reduces their overall tax burden to its lowest possible level. However, the objective needs to be to find the optimum level of tax payable rather than pure tax minimisation. The optimum level is determined by your short and long term needs and your tolerance to risk (something most farmers are fairly used to).

Tax deferral is the postponement of an imminent tax liability to a later date. This is generally only effective as a short term strategy; e.g. from one financial year to the next. Farm management deposits are an excellent tool for tax deferral and your adviser can give you the details on these.

By all means minimise your tax, but don’t spend $10 to reduce your tax by $3. What you do with net profit after tax is the question.

The first key for all farm businesses is to sit down around the kitchen table and work out your priorities for the short, medium and long term. I have found that breaking this down into quarterly, yearly and even five and 10 year plans brings clarity to what it is that you want to do. Once you have agreed on these plans, it makes it easier to then look at the profit and decide what to do with it! For example, if the business owners of the ‘Local Farm’ want to purchase a neighbouring property in three to five years, then they will need to ensure they are in a strong position to do this via cash and debt funding. If they need to educate three children starting in eight years time, how can this be done? All of these strategies need to be clearly thought out, and will have different cash flow and tax consequences. Your advisers can help you through this process.

So once you have come up with your list of plans, you can then allocate profits (and potential profits), debt or even equity to these plans. We have just been through around 20 years of relatively liquid credit conditions in Australia. Bank funding, apart from a bit of tightness through the Global Financial Crisis, has been readily available for the most part, and at mostly low rates historically. This can create a false sense of security for borrowers, where we have had increasing land prices and low interest rates and easy credit, allowing those with high gearing levels to build wealth via capital growth in excess of the cost of the funding. Wealth is only created if debt is employed to provide a return greater than its cost.

However, these conditions may not always persist. If we look at the estimated rural debt market in Australia at present, the total debt is around $60 billion. Sounds like a big number, but consider that the housing debt in Australia is $1.579 billion and the credit card debt alone is $48 billion! Warren Buffett once said “When you combine ignorance and leverage, you get some pretty interesting results.”

These numbers probably suggest that the rural debt is not excessive, but everything is relative. If for example global financial conditions worsened, and given that the Australian banks secure around 50 per cent of their funds from overseas, then the ability to borrow money in Australia, even for sound farming businesses, may become much more difficult at some point.

We are also in the middle of experiencing the lowest borrowing rates on all types of debt but again, this will not last forever. If you assume that around 70 per cent of rural debt in Australia is unhedged (that is, variable rate) then at current interest rates averages of around five per cent this is an annual interest bill for the variable portion of $2.1 billion. If rates move to six per cent, the interest bill rises to $2.5 billion. At 8.5 per cent the bill is $3.57 billion and if we go back to the late 80s with rates of 18 per cent the bill would be $7.56 billion! The point here is that one of the biggest risks to agriculture is the rising rates on a high level of debt. This is a key consideration when deciding what to do with your profits. If our ‘Local Farm’ did not have any fixed rate debt, and rates went to 8.5 per cent from the current five per cent, then interest costs would become $208,250 and cash surplus would become a cash deficit of $41,813.

Figure 1 shows the Reserve Bank cash rate (cash), 90 day bank bill rate (3M), three year fixed rate (3Y) and five year fixed rate (5Y) all without customer margins.

Figure 1: Reserve Bank cash rate (cash), 90 day bank bill rate (3M), three year fixed rate (3Y) and five year fixed rate (5Y) all without customer margins. (Source: ANZ Bank)

Hopefully this adds some clarity to the decision around whether to pay some debt off, or to ensure your interest rate risk is managed. Debt reduction can be great as:

- It gives you a good return of your current debt interest rate.

- It creates a financial reserve (equity or undrawn debt).

- It allows you to make decisions without as much stress.

Paying debt off does require you to pay tax. I don’t think there is a way around this, but certainly consult with your accountant or adviser. Principal debt reduction comes from after tax cash surplus. You do not get a tax deduction for paying debt back. Our ‘Local Farm’ therefore has a total of $183,937 of cash surplus after tax is paid to allocate to a range of decisions. The $100,000 that has been allocated to capital expenditure must be weighted against the other goals of the business. If the entire cash surplus was allocated to debt reduction, the total debt would be paid off in around 10 years, and the interest saved would be $556,674!!

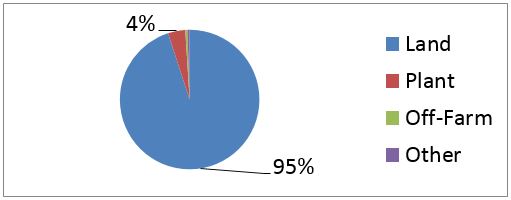

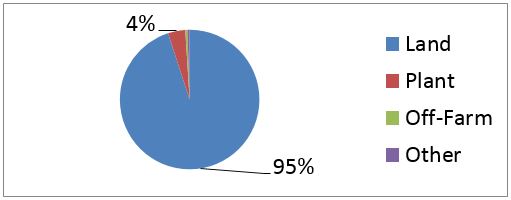

However, the reality is that there will likely be other priorities that need to be funded over the coming 10 years and longer. Something that I am passionate about is investing off-farm. I have met with dozens of farming families who are grappling with how to allocate capital to retiring partners, to siblings not returning to the farm, or to deal with an emergency, usually when time is not on their side. Figure 2 represents what I presently think the average farm balance sheet looks like.

Figure 2: Average farm balance sheet.

Note that the percentages for off-farm and other do not even register (i.e. less than one per cent)! I am generalising here, but the point is that most farm businesses have the majority of their capital invested in one class of asset. The good thing is that this has been a strongly performing asset class over many years. The average annual total farm return (operating and capital gain) for mixed farms in NSW over the last 25 years has been 9.01 per cent (Eves, 2014). If you are a strong performer, the returns will be better that this. So by having all your eggs in one basket, you have not underperformed. However, when it comes to risk and the previously identified issue of liquidity for other capital requirements, this is where the problems lie.

If we can get farm businesses to start early with planning, get some good (appropriate) advice, and build some off-farm wealth using the power of compounding over time, the eventual decisions around retiring independently of the farm, educating children, paying out other family members or even expanding into other ventures will be more easily made.

We have done some sample numbers using the projected cash surplus of our ‘Local Farm’ to show the power of starting early and reinvesting the income from an off farm investment, and comparing this to paying down debt. The difference is not dramatic, but again the key is that building the off farm investment builds buffering and options into the business. A number of scenarios were modelled. In all cases we have used a 20 year timeframe, with Farmer Joe being 47 years old in year 1:

Scenario 1: Paying down debt – cash available after capital expenditure and discretionary drawings was applied to debt reduction each year

Scenario 2: Contributing cash surplus to an off farm investment and reinvesting any income from this investment into the off farm investment.

Scenario 3: As per Scenario 2 but with additional $100,000 starting balance to come from inheritance, borrowed funds or sale of surplus equipment!

Scenario 4: As per Scenario 3 but with additional $50,000 per annum from capital expenditure budget.

The results of each scenario are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Net wealth generated from the different scenarios 1-4.

|

Net Wealth |

$ Different to 1 |

$ Off Farm |

% Off Farm |

|---|

| Scenario 1 |

$ 33,356,663 |

$ - |

$ - |

0% |

|---|

| Scenario 2 |

$ 33,914,226 |

$ 557,563 |

$ 1,832,514 |

5% |

|---|

| Scenario 3 |

$ 34,308,511 |

$ 951,848 |

$ 2,226,799 |

6% |

|---|

| Scenario 4 |

$ 36,023,697 |

$ 2,667,035 |

$ 3,941,986 |

10% |

|---|

Now consider the effect if our ‘Local Farm’ had started investing off-farm earlier, given that even in these scenarios the percentage allocation to off farm is still relatively low (the farm keeps increasing in value every year).

The keys to this strategy of off-farm investment include the following:

-

Start early, even with a small amount.

-

Add to it on a regular basis (every month is good – compounding is the eighth wonder of the world).

-

Keep focused on your long term goals.

-

Diversify – don’t have all your eggs in one basket.

-

Get some great advice – it will cost you but it will be worth it.

-

Do not withdraw.

-

Start with a lump sum (or add a lump sum) where possible.

-

Stick to the plan.

Conclusion

The decision around how to allocate farm cash surplus funds is one of the most strategic and important in long term wealth creation in a farm business. It has tax consequences, risk consequences and ultimately personal consequences as well. It needs to continually reference your long term strategies and be flexible in changing circumstances.

Off farm investments should form part of this strategy. A spread of investments, apart from land and machinery, offers flexibility in decision making around future investments, retirement planning, succession planning and disaster recovery planning. Start this journey early and be consistent. Compounding is an amazing trait.

The rural debt picture needs to be seen in context of a prolonged period of relatively easy credit conditions, low interest rates and rising land prices. There may be a day when loans are not as easy to obtain, interest rates are rising, property prices are falling or a combination of these factors. Being aware of the impact of these factors on your business and what your parachute option is are critical to long term business survival and wealth creation. Build in some buffering by keeping debt levels at a manageable level and hedge interest rates where appropriate. Remember, interest is a cost of production of any business, so again get some advice to ensure you are paying a competitive rate, but also that the conditions of your loan are reasonable.

References

Eves, Chris 2014. The Analysis of NSW Rural Property Investment Returns: 1990-2014, QLD University of Technology.

Farm Policy Journal Vol 13 No 2 Winter Quarter 2016 Australian Farm Institute – Understanding the Value of Agricultural Land

ANZ Bank Treasury – Interest Rate Graphs

Contact details:

James Smith

North West Agrifinance and North West Wealth Management

442-450 Goonoo Goonoo Road, Tamworth NSW 2340

02 67624244; 0408 565196