Identification detection management and implications of Russian Wheat Aphid

Author: Melina Miles, Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Toowoomba | Date: 21 Jul 2016

Take home messages

- Do not assume aphids in cereals are just the usual oat and corn aphid. In the event of a Russian wheat aphid (RWA) infestation, early detection in spring is critical to prevent yield loss.

- Multiple aphid species may occur in the same crop.

- Conditions suitable for the usual cereal aphid species will also be suitable for RWA. Aphid populations typically build rapidly in late July and August.

- Familiarise yourself with the symptoms of RWA infection (white streaks, reddening, leaf rolling). These may be the first things you notice in a crop.

- Prophylactic spraying will not reduce the likelihood of RWA infestations, and may increase the likelihood by killing off beneficials.

- Report suspect aphid incidence to NSW DPI, or QDAF depending on location – contact details provided in the paper. Until confirmed as present, RWA is a notifiable pest in these states.

Introduction

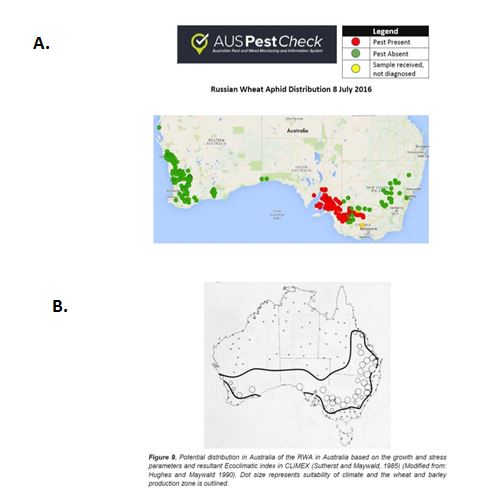

Russian wheat aphid (RWA) (Diuraphis noxia) was identified from wheat crops in the mid-North of South Australia in May 2016. On 8 June 2016, the National Management Group (made up of all state and the federal governments, Grain Producers Australia and Plant Health Australia) determined that it was not technically feasible to eradicate RWA from Australia. Subsequently, RWA has been confirmed from numerous locations across SA and Victoria. The maps show A) the distribution at 8 July 2016 (Plant Health Australia Biosecurity Portal), and B) the potential distribution of RWA in Australian grain production based on modelling climatic suitability (Hughes and Maywald 1990). This modelling suggests that all Australian grain production regions are suitable for this pest. RWA has a large number of grass hosts, on which it can survive, including over summer. Sorghum is not known to be a host.

Figure 1. (A) The distribution of RWA at 8 July 2016 (Plant Health Australia Biosecurity Portal) and (B) the potential distribution of RWA in Australian grain production based on modelling climatic suitability.

RWA as a pest in the Northern grains region

RWA is considered a high priority pest by the grains industry because of its potential to cause significant yield losses in wheat and barley if not well managed. Triticale and rye are also susceptible to crop loss, but oats are considered relatively tolerant.

Although RWA is more damaging to cereals that the aphid species we already have in Australia, the susceptibility of Australian varieties is unknown. While potential yield losses of 60+% are reported overseas where RWA were not controlled, international experience with RWA has been that in seasons following initial outbreaks, yield losses are generally lower as growers become better equipped to detect and manage infestations, and natural enemies establish and contribute to the suppression of populations.

It is inevitable that RWA will establish in the northern grains region, but we don’t know when we will start to see it in crops. It may be this spring, or it may not be for several seasons. It is likely that RWA movement will occur in late spring and early summer, as winter hosts start to die off, and will be facilitated by wind.

It remains to be seen whether RWA over-summer on grass hosts within the cropping landscape. If so, early sown winter cereals will be at high risk from RWA infestation because of proximity to summer hosts and the suitability of the relatively warm autumn conditions in the northern region for aphid build up. In the short term, until tolerant/resistant varieties are available, seed dressings are an option worth considering for 2017 planting to minimise the risk of crop loss in autumn. <

In the 2016 season, it is important that crops are monitored regularly and more thoroughly than they might usually be checked.

RWA identification and distinguishing it from other aphid species

Table 1. RWA identification and distinguishing it from other aphid species

|

|

Russian wheat aphid |

Rose grain aphid |

Oat aphid |

Corn aphid |

|

(***=key features) |

(GRDC Crop Aphids Backpocket Guide) |

|

|

Photo: R. Daniels |

|

Colour*** |

Bright green |

Green, yellow-green with darker green stripe down midline of back |

Green to dark green-black. Base of abdomen rusty red |

Green to dark green. Base of siphuncles with red patches |

|

Body |

Up to 2mm long |

Up to 3mm long |

Pear shaped, up to 2mm long |

more rectangular than rounded |

|

(tail) |

Protruding, double*** |

Protruding, single |

Visible, single |

Visible, single |

|

(exhaust pipes) |

None visible*** |

Obvious |

Obvious, dark-tipped |

Visible, short |

|

Antennae |

Short with dark tips |

Almost the length of the body, with dark tips |

Long |

Short, dark |

Aphid identification resources:

- GRDC Crop Aphid Backpocket Guide

- I Spy – Insects of Southern Australian Broadacre Farming Systems Identification Manual

Leaf symptoms caused by RWA infestations

RWA induce striking symptoms in wheat and barley, unlike the oat and corn aphid which produce no obvious symptoms. Plant damage is in response to direct aphid feeding, so only the leaves and/or tillers infested show symptoms, which usually appear within a week of infestation.

1. White streaking of the leaves. Some varieties show reddening.

Figure 2. White and red streaking of the leaves.

2. Rolled leaves. RWA colonies shelter inside the rolled leaves.

Figure 3. Rolled leaves

3. Infestation of plants up to head emergence can result in rolling of the flag leaf, resulting in the head being trapped in the boot.

Figure 4. Infestation of plants up to head emergence can result in rolling of the flag leaf.

Some of these symptoms are similar to those caused by wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV) and phenoxy damage in cereals – close examination of symptomatic plants to determine the presence of RWA is recommended.

If RWA are detected in crops in NSW or Qld, notify the relevant authority. Until the first confirmed detections in these states, RWA is a notifiable pest. No detections confirmed at 20 July, 2016.

Table 2. RWA reporting information.

|

Jurisdiction |

Reporting information |

|

New South Wales |

Exotic Plant Pest Hotline 1800 084 881 or reports are requested using the online RWA Reporting Tool |

|

Queensland |

Reports request to Biosecurity Queensland on 13 25 23 or email photos of symptoms/aphids to plantpestdiagnostics@daf.qld.gov.au. |

|

National |

Exotic Plant Pest Hotline 1800 084 881 – calls to the Hotline are transferred to contact points in each jurisdiction |

Monitoring, thresholds and control options for RWA in spring 2016

Research in the US and in South Africa in the 1990s, following the arrival of RWA, established sampling protocols and economic thresholds. These overseas recommendations are provided as guidance in the absence of local data at this time.

Spring is a critical time to be alert to the presence of RWA. Conditions are generally suitable for the rapid build-up of aphid populations, and wheat and barley are most susceptible to yield loss when RWA infestations are present between Zadocks 30 and 59.

The priority with RWA management during spring is to control populations to:

- prevent loss of photosynthetic capacity of the flag, flag-1 and flag-2 leaves as a result of chloroplast death (white streaking), and leaf rolling caused by direct RWA feeding, and

- avoid the curling of the flag leaf that can trap the head as it emerges

Like other aphid species, RWA densities are higher on stressed plants. It is worth inspecting any areas of stressed plants specifically for RWA. Also check for RWA on grass weeds and volunteers.

Provisional thresholds recommended in South Australia for RWA are 10% of tillers infested (aphids present) from Z30-59. For younger crops, a threshold of 20% of plants/tillers is suggested. These recommendations are based on overseas thresholds which were formulated some years ago and may not be current for costs of control, grain prices and yields.

A simple calculation of the cost of 10% yield loss caused by RWA (not accounting for any possible compensation) shows it would be considerably more than the cost of applying an insecticide (in crops with a potential yield greater than 2 t/ha). For the northern region, I propose the use a threshold of 5% infested tillers for crops with a yield potential over 2 t/ha. Crops expected to yield 2 t/ha or less, should use the 10% threshold. [Based on grain price of $180-240/t and cost of control around $30/ha].

Clearly validation of economic thresholds is a priority area for research.

Suggested strategies

Sample tillers and score the presence of aphids.Each tiller is scored as infested (or not), and the level of field infestation is calculated as a percentage of sampled tillers. For example, 100 tillers sampled from across the field; 35 tillers had RWA present; therefore the field has an infestation rate of 35%. A tiller-based sampling protocol is simpler and more reliable than counting aphid numbers, which can be very variable between tillers and very time consuming to do on whole plants.

Sample tillers randomly from across the field.It is not known whether RWA infestations will display the edge effect often seen with other aphids (densities are highest around field edges where the aphids have moved in from nearby hosts, or been concentrated by movement on prevailing winds). A random sampling approach provides the best chance of encountering a patchy pest like RWA.

If aphids require treatment, use the least disruptive option available. Pirimicarb is effective and will not kill beneficial insects that will then be able to eat aphids that might survive the treatment. Chlorpyrifos and pirimicarb are available for use under permit (PER81133) for RWA, and both are reportedly effective against RWA. RWA is not known to have any resistance to insecticides. There is currently some uncertainty around the effectiveness of the registered rate of Transform ® (50-100 mL/ha 240 g/L sulfoxaflor for cereal aphid control) for RWA. Dow Agrosciences is undertaking trial work to clarify the situation. Judicious insecticide use will ensure that aphid populations are not ‘flared’ by killing off natural enemies that might otherwise supress infestations to sub-threshold levels; and avoid unnecessary cost from applying insecticide that is not required.

Consider beneficials. In South Australia and Victoria, where RWA are widespread, the majority of fields have infestations well below economic threshold, and have not been treated with insecticide. Cool, wet winter conditions have suppressed populations, and there is evidence of natural enemy (beneficial) activity. Ladybeetles, lacewings, hoverflies and parasitoids have all been recorded attacking RWA in Australia.

Resources

- GRDC Crop Aphid Backpocket Guide

- Plant Health Australia Biosecurity Portal (RWA distribution map, factsheets) (https://portal.biosecurityportal.org.au/rwa/pages/home.aspx)

- The Beatsheet. Northern region newsletter. QDAF. (www.thebeatsheet.com.au)

- Pestfacts SA . PIRSA/SARDI newsletter with updates on RWA and other pests. (http://pir.sa.gov.au/research/services/reports_and_newsletters/pestfacts_newsletter)

- Pestfacts south-eastern. Cesar. Newsletter for the southern region (Vic and Sth NSW). (http://cesaraustralia.com/sustainable-agriculture/pestfacts-south-eastern/)

Hughes RD & Maywald GF. 1990. Forecasting the favourableness of the Australian environment for the Russian wheat aphid, Diuraphis noxia (Homoptera: Aphididae), and its potential impact on Australian wheat yields. Bulletin of Entomological Research 80: 165-175.

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC, the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

Contact details

Dr Melina Miles

Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

203 Tor St, Toowoomba.

Melina.miles@daf.qld.gov.au

Mobile: 0407113306

Office: 07 46881369

GRDC Project Code: DAQ00196,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK