Introduction

“The key task of farm management is making choices between alternatives. Farm management analysis is about analysing those choices (and) encompasses considering alternative actions under risky and uncertain circumstances” Malcolm, Makeham and Wright, The Farming Game, 2005.

The choice of enterprises within a farm system remains a complex decision with a range of possible scenarios. There is generally no best bet system; differences in climate, soil type, market access, labour and management all contribute to the need for land managers to negotiate a system which fits their individual needs. A general outcome being sought from the farming system is profit maximisation at an acceptable level of risk.

There remain, however, some core characteristics of farming systems which enable them to be successful over a period of time. These include:

-

Appropriate level of income diversification. Virtually all cropping systems in South Australia involve some level of diversification. The traditional approach has been to include livestock although most farm systems in more favoured cropping locations have moved away from livestock. These areas tend to have a more diversified range of crop options than lower rainfall systems.

-

Adoption of right rotations, along with attention to detail. “Right rotations pay- they don’t cost”. This catch cry from the Right Rotations initiative in the 1980s continues to be relevant. Appropriate crop sequencing involves decisions around weed, disease and nutrition implications along with other considerations such as herbicide residues, carry-over of water from previous crops, etc. There is also no substitute for good agronomy and/or livestock husbandry.

-

Understanding and acknowledging comparative advantage. This applies both to the business location and the technical and personal characteristics of business managers. Some crops are just not suitable to be grown in certain areas, and some people just should not run livestock! Understanding and working with variations in land capability across farms is important.

-

Meeting market requirements. Our mixed farming systems in SA have traditionally produced grain and livestock products which generally have had good demand and acceptance on world markets. The caveat here is that even though market acceptance is good, difficulties can arise when supply and demand get out of balance resulting in poor prices which test farm business profitability.

We can look at how recent changes are impacting on each of these characteristics particularly with reference to the financial and risk aspects.

Income diversification

Cropping

There has been subtle but significant change in crop diversity over the past decade. Traditionally, virtually all rotations in SA were cereal based, with wheat largely king. However, recently we have seen the emergence of the concept of wheat as a break crop to more valuable alternatives. Examples of this are canola on Lower Eyre Peninsula and lentils on Yorke Peninsula. Integral to this evolution has been the adoption of new and/or cheaper technologies such as herbicide tolerant varieties and cheaper fungicides.

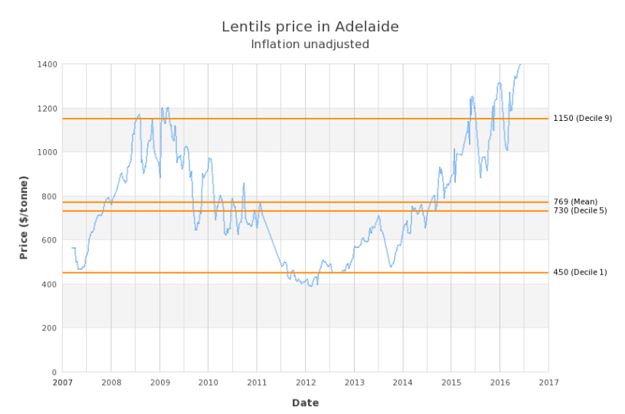

The unintended consequence of the success and subsequent expansion in these crops has been the upward pressure it has placed on land and land leasing values. Examples are prime Yorke Peninsula land approaching $7000/ha with lease values up to $500/ha. In these locations, it is very difficult to justify current land acquisition costs on anything other than the continued success of these high value alternative crops. What could potentially impact on this success? The agronomics seem to be working well, so potentially price could be the issue. Current (August, 2016) pricing of lentils around $800/tonne remain above Decile 5 levels (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Historic lentil pricing (10 years delivered Adelaide)

(Source:

Grain and Graze).

In the case of lentils, the high levels of past profitability demand that they need to be continued to be included in the rotation at a high level. In most cases, and even where high lease prices are being paid, the risks are being balanced by other business’s strengths, such as ‘old money’.

Livestock

The ley farming system in southern Australia (e.g. the wheat/ sheep system) has been traditionally based on crops (usually cereals) rotating with some sort of self-regenerating, usually leguminous pasture. These systems remain common in lower rainfall cropping environments, although there has been a trend towards annual sowing of pastures rather than relying on self-regeneration. In more favoured cropping locations, livestock have become a rare commodity.

There have been many studies done on crop/livestock interaction and there remains a degree of polarisation in the value of livestock inclusion in farming systems. Where livestock are well adapted to an environment and particularly in lower rainfall cropping systems, many farmers still regard them as an important tool for risk management. However, even in these regions, there are also a significant number who have removed livestock from their system, presumably due to concerns with compromises which livestock bring to the system. Modelling suggests that synergies for the farming system between crop and livestock are wide ranging and occur over a range of cropping intensities, although it should be noted that modelling in this area is complicated and the results are very dependent on assumptions adopted.

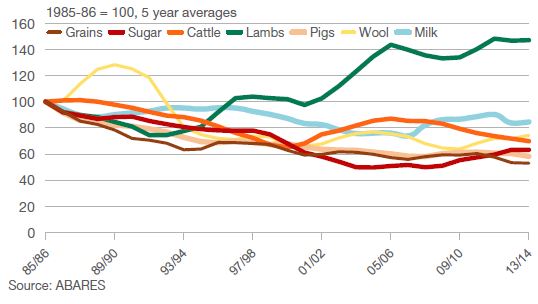

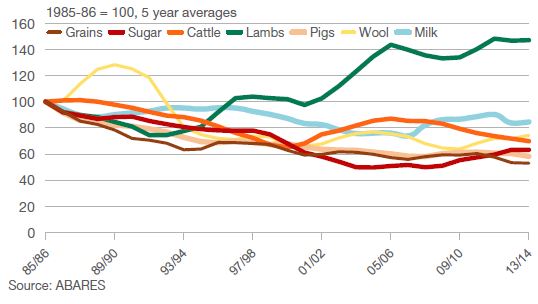

The significant recent change in crop/livestock economics has been the change in output pricing levels. Figure 2 compares real (inflation adjusted) prices for several commodities over the past 30 years. Most commodities have seen a general decline in real value, with the exception of lamb pricing which has climbed in the presence of fundamental changes in the world demand for meat. Currently, a prime lamb can be sold for as much or more than a tonne of cereal grain and is (arguably) easier and cheaper to produce.

Figure 2: Historic real commodity prices (5 year average) showing the growth in the value of lambs compared with other commodities including grains (Source: ABARES, MLA).

The long awaited recent rise in beef prices adds weight to the value now being gained from livestock enterprises on mixed farms. And, of course, price is only a part of the profitability picture. High costs (chemicals, fertiliser, machinery, etc.) associated with high input cropping farms have been regularly identified as contributing to high debt exposure, higher risk and reduced profitability. So the case for an increased emphasis on livestock in a mixed farming system seems to have been enhanced in recent years.

Also a noteworthy innovation is the ‘Grain and Graze’ technique of choosing to ‘harvest’ crop biomass with either a machine, livestock or a combination of both. While this has yet to become widespread in SA, there are clearly opportunities to change our approach in this area.

For more information see:

The important caveat on the use of livestock for financial risk management is the implementation of a systems approach to maximise their beneficial uses and reduce the antagonistic impacts. Benefits include the production of ‘free’ nitrogen from well managed pastures and integrated weed management. Farmers also have well defined exit strategies for livestock during dry or drought periods; these might include confinement feeding land ownership or agistment in more favoured areas (including negotiating long-term arrangements), use of trading stock, etc.

Crop sequencing (rotations) and good agronomy

Use of break crops

With the exception of favoured cropping regions with alternative crop choices, intensive cereal based rotations have been the norm as producers have responded to cost pressures by attempting to grow more product, but avoiding other crops seen as higher risk.

However, the recent GRDC funded Low Rainfall Crop Sequencing Project (DAS00119) has shown that well managed break crops can be profitable even in regions which traditionally did not favour these crops. In addition, the research showed that when break phases were incorporated, increased profitability of up to $100 per hectare per year could be achieved over a four-year period compared with cropping continuous wheat. The key to increasing profitability was having at least one profitable break crop option that manages agronomic constraints, and therefore, increases the production of subsequent crops. Wheat yield benefits were commonly 1–2t/ha over 2-3 seasons following the break phase. For more information see:

Flexible rotations

Another area of debate is the value or otherwise of increasing the flexibility of enterprise selection between years. As an example, farming businesses in the lower rainfall districts make a greater portion of their profit in a few good seasons. Maximising the value of the good years and reducing the downside in poor years is particularly important. It follows that flexibility to respond can have many advantages. However, while there are gains in flexibility, there are also costs and some advocate a less responsive, fixed approach. So debate lies in two areas:

-

The effectiveness of trigger points in changing decisions and improving profits e.g. crop area, crop inputs, livestock strategies, etc.

-

The cost of reduced flexibility if long-term planning horizons are adopted.

There are clearly successful operators in both camps so it is difficult to advocate either way.

Good agronomy

There have been substantial advances in farming systems which is reflected in the increase in the water use efficiency of farm systems which has been observed across cropping regions. Summer weed control, precision agriculture, improved varieties and better weed and disease control packages are examples. The downside is that these advances almost invariably come at the cost of higher inputs. The requirement then is for a fundamental understanding of marginal costs versus marginal returns. Leading operators have a shrewd understanding of the marginal cost/ marginal return debate. This manifests itself in their ability to maintain/ improve productivity with lower input costs and subsequent gross margin benefits.

Comparative advantage

As outlined above, there has been a significant recent move towards break crops in areas which would have traditionally relied on cereal cropping. Crops such as lentils, field peas and chickpeas are showing increased adoption. Recent very good prices have been a significant driver of adoption but improved varieties and better agronomy has also been important in allowing these crops to be successful in environments which would traditionally have not favoured these crops.

Precision agriculture is allowing operators to better identify poorer performing areas of their properties with the aim of adjusting the landscape use to more profitable enterprises e.g. replacing poorly productive cropping areas with pasture for livestock.

Meeting market requirements

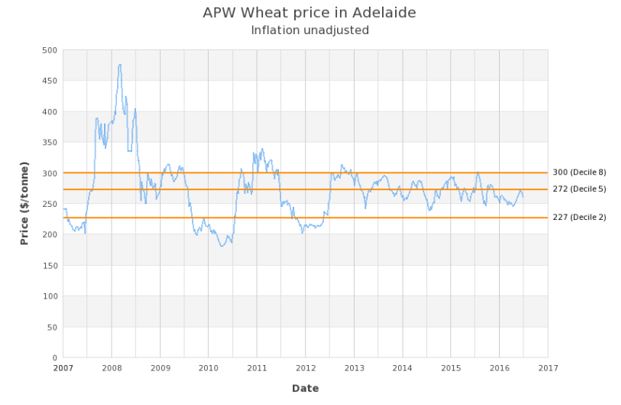

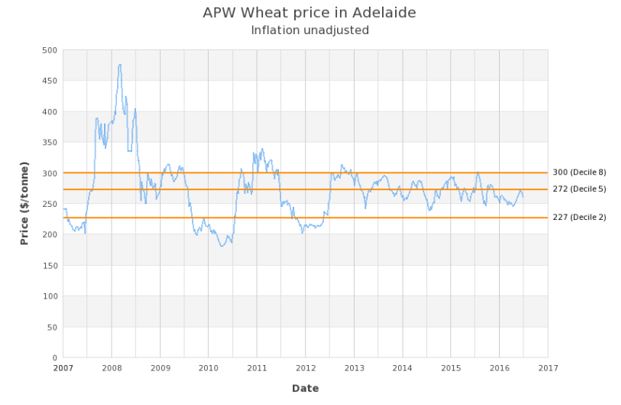

Recent declines in cereal prices have focussed attention on the ability of other cereal grain exporters to supply wheat into our traditional markets at very competitive prices. Current (August, 2016) APW wheat forward price for the 2016/17 harvest at $235/tonne is just above the 10 year Decile 2 price level (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Historic wheat pricing (10 years delivered Adelaide) (Source:

Grain and Graze).

I would argue that there would be very few wheat growing businesses in SA which would have full costs of production for wheat at or below $235/tonne. At these prices, wheat growing businesses are relying on above average yields or support from other sectors of their business to maintain profitability. This is a dangerous position if it continues into the future.

Tools and techniques for decision support in enterprise selection

Simple gross margin analysis

Nothing beats good records and a historical display of on-farm gross margins for individual crops as an aid for future enterprise selection. There are a number of very good products available for this purpose; seek advice if unsure.

Comparative gross margins can provide a good insight into the profitability of alternative enterprises particularly if combined with a sensitivity analysis relating to varying yields and prices. The obvious weakness of gross margin analysis needs to be recognised and understood. A recent very useful innovation in 2016 was the Excel based editable version of the Rural Solutions Farm Gross Margin Guide which allows very quick and easy gross margin comparisons for all major crops in SA. Available as a download form GRDC, PIRSA and SAGIT websites

Farm Gross Margin Guide.

More complex analysis using Excel add-on tool @Risk

The value of the @Risk program is that it can allow the treatment of multiple risks (e.g. climate and price). Farmer feed-back from use of such programs has been very good. They satisfy the requirement that the Decision Support System inform farmer’s intuition rather than provide optimum solutions. The downside is the need for a skilled operator to interpret the individual farmer’s situation to deliver robust simulations.

Conclusion

Farming system and enterprise selection to meet the goals of producing profitable outcomes at acceptable levels of risk is an ongoing challenge which requires a high level of understanding of all aspects of the physical and financial environment. It is dangerous to be specific; each circumstance will be different and what is good for one will not fit others. Being prepared to adapt and change seems to be the highest priority. A commitment to building human capital through training and education will go a long way in developing the necessary skills to address the important issues.

Contact details

Barry Mudge