The impact on Australian agriculture of Britain leaving the European Union

Author: Mick Keogh (Australian Farm Institute) | Date: 10 Aug 2016

Introduction

On Thursday 23rd of June, 2016, the citizens of the United Kingdom (UK) voted in a referendum which asked whether the UK should continue as a member of the European Union (EU), or leave. The resulting vote was 52 per cent to 48 per cent in favour of the UK leaving the EU and the government of the UK has stated it will give effect to that decision.

The EU is an economic and political partnership involving 28 European countries. It began after World War Two to foster economic co-operation, with the idea that countries which trade together are more likely to avoid going to war with each other. It has since grown to become a ‘single market’ allowing goods and people to move around, basically as if the member states were one country.

For the UK to leave the EU it has to invoke an Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty (the founding document of the EU) which gives the two sides two years to agree to the terms of the split. The new UK Prime Minister has said she will not kick-off this process before the end of 2016. This means that there will not be a clear idea of what kind of deal the UK will seek from the EU, on trade and immigration, until at least mid-2017. It is likely that subsequent negotiations will extend well beyond that time, and it could be up to five years before the separation is in effect.

While the potential terms of a UK exit from the EU remain quite unclear, it is reasonable to assume that there will be three major implications of this decision which have potential implications for Australian agriculture. These are;

- Agricultural trade between EU nations and the UK will no longer be free of any tariffs or restrictions,

- the movement of people (especially workers) between the UK and the EU will face increased restrictions, and;

- the large subsidy that UK farmers currently receive from the EU each year will cease, but may be at least partly replaced with subsidies from the UK Government.

The remainder of this paper examines each of these issues in more detail, before finally analysing what the implications of this change may be for Australian agriculture.

Implications for agricultural trade

The UK has long been a net importer of agricultural products, as can be observed in Figures 1, 2 and 3. The value of agricultural imports by the UK increased dramatically in the immediate aftermath of World War Two as international trade resumed and the UK economy underwent recovery. UK agricultural imports again grew rapidly from 1973 as The UK’s entry to the EU encouraged imports from other EU nations. A third spike in UK agricultural imports occurred in the aftermath of the major Foot and Mouth Disease outbreaks in the early 2000s, when large numbers of UK livestock were destroyed and strict regulations were imposed on the UK livestock industries.

Figure 1: Trends in UK agricultural trade (1936-2011).

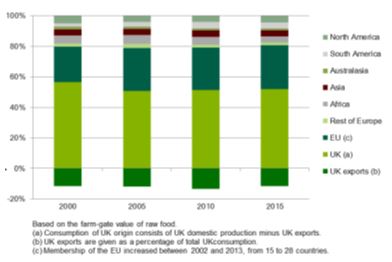

Figure 2: Origins of food consumed in the UK. (Source: DEFRA, 2015).

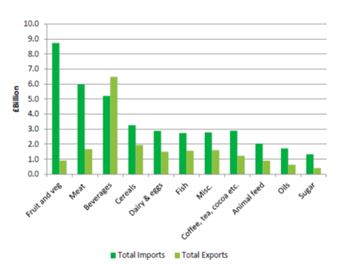

Figure 3: UK trade in different food groups. (Source: DEFRA, 2015).

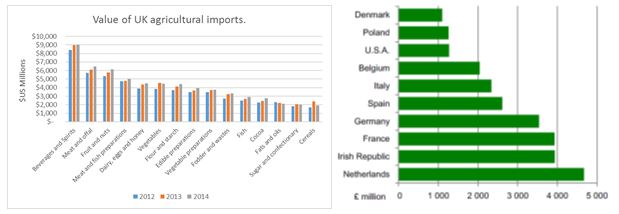

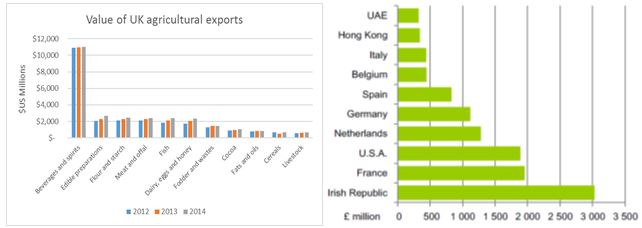

Major UK agricultural and food imports include wine and spirits, meat, fruit and vegetables and a wide range of semi-processed and processed foods. As can be observed from Figure 4, UK agricultural imports are dominated by products sourced from EU nations; hardly surprising given the proximity of the UK to mainland Europe, and the free trading environment that exists between the UK and EU nations.

Figure 4: Value and source of UK agricultural imports.

The UK is a significant exporter of a number of agricultural and food products; specifically whisky, lamb and dairy products. More than two thirds of UK agriculture and food exports are destined for EU nations.

Figure 5: Value and destination of UK agricultural exports.

The UK was one of Australia’s major markets for agricultural exports during the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth centuries. At the end of the second world war, the UK imported one third of all Australian agricultural exports, including 80 per cent of all beef exports and 90 per cent of all butter exports (Pollard, 2000). During the 1960s, the USA, Japan and Korea grew in importance as export markets, followed more recently by the emergence of the Middle East and Asia as major markets.

The UK joined the European Union in 1973 which resulted in tariffs and quotas being applied to Australian agricultural exports destined for the UK, and by the mid-1980s, the UK was taking less than two per cent of Australian rural exports. At that time, the major markets for Australian agricultural exports were Japan (21%), the Middle East (15%), North America (12%), the EU (11%), Eastern Europe (9%), South East Asia (9%) and China (5%).

By 2015, Australia’s agricultural exports were predominantly destined for North Asia (including Japan, Korea and China) which collectively accounted for more than 40 per cent of total exports of which 20 per cent was China alone, followed by South-East Asia (20%), the Americas (14%), the Middle East (7%) and Europe including the UK (5%).

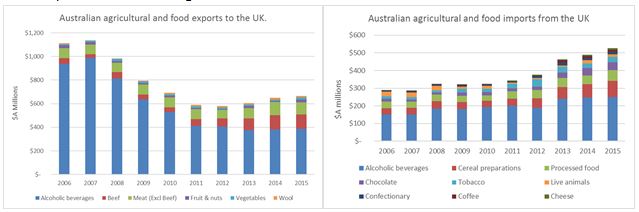

Australian agricultural and food exports to the UK in 2015 accounted for around 1.5 per cent of Australia’s total agriculture and food exports. Principal among these were wine, lamb and beef. Of note over recent years there has been the significant decline in the value of Australian wine exports to the UK, as other ‘new world’ suppliers such as New Zealand, Argentina and the US have become more prominent in export wine markets. In contrast, Australian beef exports to the UK have been growing as a result of both higher beef prices and some increases in quota access under EU agricultural trade arrangements.

Australia also imports agricultural and food products from the UK; predominantly alcoholic beverages (whisky) and a variety of processed foods. Australian agricultural and food imports from the UK have been increasing over recent years in line with the general growth in the value of food imports to Australia, especially over the period of relatively high Australian dollar exchange rates as a consequence of the mining boom.

Figure 6: Australia’s agriculture and food trade with the UK (major products).

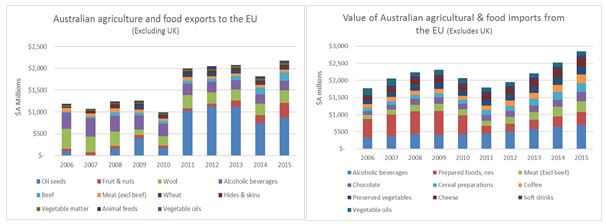

Australia also has significant two-way agricultural trade with the EU as is evident from Figure 7. Principal Australian exports to the EU include canola (as a consequence of demand driven by the EU biofuels mandate), wine, fruit and nuts, wool and beef. Total Australian food and agriculture exports to the EU (excluding the UK) were valued at approximately $A 2.3 billion in 2015 and have been relatively static over recent years. Australia’s agriculture and food imports from the EU were valued at approximately $A3.8 billion in 2015, and consisted predominantly of wine and processed foods, as well as canned vegetables (tomatoes from Italy) and pigmeat sourced from Denmark and the Netherlands.

Figure 7: Australia’s agriculture and food trade with the EU (major products).

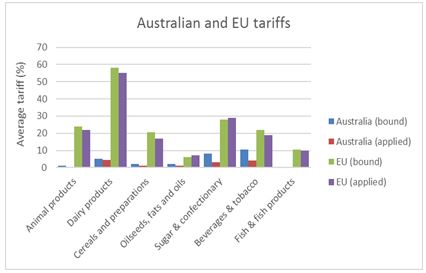

Australia has an agriculture and food trade deficit with the EU, part of the explanation for which is the restrictions that are applied by the EU to agriculture and food imports from Australia. Figure 8 displays the tariffs that are applied to imports of agricultural products by Australia and the EU respectively. Applied tariffs are those that are estimated to be currently applied, whilst bound tariffs are the maximum tariffs each trading partner is legally able to apply under World Trade Organisation (WTO) agreements on a Most Favoured Nation (MFN) basis. (Source: Hussey & Tideman, 2013). The graph highlights the significant disparity between the tariffs faced by Australian agricultural imports into the EU, and EU agricultural imports into Australia.

Over all agricultural products, Australia import tariffs average 1.2 per cent, while EU tariffs average in excess of 12 per cent.

Figure 8: Bound and applied tariffs on trade in agriculture and food products.

Australia’s red meat exports also face quota restrictions in the EU market. Australia’s red meat exporters have exclusive access to:

- 7,150 tonnes of high quality beef quota at an ad valorem tariff rate of 20 per cent, and;

- 19,186 tonnes of sheepmeat and goatmeat quota at a zero tariff rate.

In addition, there are also two global red meat quotas, administered by the EU, that provide Australian exporters with additional access on a first-come-first-served basis. These are a:

- 48,200 tonnes of high quality grain fed beef quota at a zero tariff rate, and;

- 200 tonnes of sheepmeat and goatmeat quota at a zero tariff rate.

The latter quotas are accessible by exporters from any nation, and are not exclusive to Australia.

Against this agricultural trade background, the potential implications of Brexit for both the UK and Australia remain somewhat unclear. On a very simple analysis, the UK would no longer be a member of the EU, and agricultural exports from the UK to the EU (predominantly whisky and lamb) would therefore presumably face the same tariff rates that Australian agricultural imports to the EU face. This could result in a reduction in the value of UK agricultural exports to the EU, and a diversion of these exports to other markets.

The UK, meanwhile, would have greater autonomy in being able to set tariff rates on agricultural imports, and could conceivably increase tariffs on agricultural imports from the EU to a level equivalent to current EU agricultural tariffs. This would effectively increase the price of EU agricultural exports to the UK, with the potential result being a loss of market share by EU agricultural exporters, and a possible increase in UK agricultural production (due to increasing agricultural commodity prices), or at least an increase in UK agricultural imports from non-EU sources such as Australia.

This is probably an overly simplistic analysis however, as the impact of potential future changes in agricultural tariffs and market access arrangements can be negated or magnified by changes in exchange rates, such as have already been observed in response to the Brexit decision. The exchange rate of the British Pound has depreciated against most major currencies including the Euro in the wake of the Brexit decision. This has the effect of making imports to the UK more expensive, and exports from the UK more competitive in international markets. This will likely result in higher agricultural commodity prices in the UK relative to the price of imported products, and hence may stimulate increased farm production in the UK and a reduction in net agricultural imports.

From an Australian and New Zealand perspective (ignoring exchange rate fluctuations), the potential opportunities that are likely to emerge as a consequence of the Brexit decision are fairly limited. There may be increased opportunities for Australian exports of beef and wine to the UK (depending on how much of the current EU beef import quota is transferred to the UK), but this will depend largely upon decisions that the UK makes about the tariff regime that will be adopted post-EU membership. Bulk Australian agricultural commodities such as grains are generally not competitive in European markets due to the impact of freight costs, although Australia does export a small volume of specialised wheat to the EU. Higher value products, including red meat, wine and some horticultural products, can be competitively exported from Australia to the EU or the UK, however Brexit is more likely to result in a shift in market destinations (for example more Australian beef to the UK and less to the EU) rather than an overall increase in demand.

Compounding these issues is the question of whether or not it is possible to reliably increase the volume of agricultural production in Australia in the event that Brexit does stimulate increased demand from Britain for non-EU agricultural and food exports. The current trend in Australia of a declining beef and dairy cow herd will not be easily reversed without a sustained price increase, and Australia’s grain and oilseeds output are always more dependent on seasonal conditions than on prices. Even if the UK transferred all of its current demand for agricultural imports to Australia, it is doubtful if the extra would be sufficient to stimulate increased Australian production.

A further unknown in relation to the potential impact on Australian agriculture of Brexit is future decisions by governments about agricultural trade. Australia has already initiated preliminary discussions with the EU about an Australia-EU free trade agreement, and it seems likely that if such an agreement eventuates, there will be some downward movement in the level of agricultural tariffs imposed on agricultural imports by the EU. In the past, such changes have tended to be offset by increases in technical trade barriers (for example biosecurity and safety testing protocols) meaning that the nett impact is difficult to estimate. From an Australian agricultural perspective, it would also be advantageous to initiate trade negotiations with the UK, although that nation represents a much smaller market than the EU.

Compounding factors in relation to the impact of Brexit on both the UK and ultimately Australia are the impact of issues such as the future availability of labour for UK agriculture, and the future of farm subsidies in a post-Brexit era. These are discussed in the following sections.

UK agricultural workforce implications

One of the contentious issues that some consider was an important factor in the Brexit decision was the freedom of movement within the EU for workers (and those claiming refugee status). There was a strong view that the presence of eastern European workers in the UK and the threat of a ‘flood’ of those seeking refugee status created resentment which encouraged a stronger ‘leave’ vote in the recent referendum, and this was particularly evident in regions of Britain other than the London metropolitan region.

However, for the UK agriculture sector the availability of overseas (i.e. non-UK born) workers has been particularly important. The National Farmers Union (NFU, 2015) estimates that over the past five years, between five and six percent of all workers in the UK agricultural sector have been visiting workers from EU countries, and that these workers have been particularly important for farms producing seasonal commodities such as fruit and vegetables and associated vegetable processing businesses.

While the UK has been a member of the EU, these workers (predominantly from nations in Eastern Europe) have been able to freely move to the UK for casual employment during harvest seasons, and then travel to other parts of the EU as regional harvest seasons occur. Part of the rationale for the decision by the UK to exit the EU was that it would enable the UK to control the movement of people across it borders. Presumably this would mean that in the post-EU era, the UK could enact regulations that would allow the free movement of seasonal workers into the UK, but would prevent the movement of other persons; including those claiming refugee status. However, policies governing the cross-border movement of people are often based on mutual agreements between nations, and moves by the UK to restrict movement of people across it borders would likely trigger a policy response from the EU which could disadvantage the UK.

While any changes that would restrict the seasonal availability of workers in UK agriculture could have a negative impact on farm businesses, it is also the case that non-EU nations such as Norway and Switzerland have negotiated agreements with the EU that provide rights of free movement throughout the EU for citizens of those nations. It seems possible that a similar agreement could be negotiated for the UK, and hence labour availability may not be a major issue for UK agriculture in the post-Brexit era.

UK farm subsidies after Brexit

One of the more challenging issues facing UK farmers as a likely consequence of Brexit is that they will no longer receive the generous EU agricultural subsidies that are associated with EU membership.

Under the current EU Common Agriculture Policy (CAP) the average farmer in England and Wales receives direct subsidies of £235 and £179 per hectare ($A412 and $A314) each year. There are also payments available under agri-environmental and other schemes, with the total EU payments to UK farmers exceeding £2.8 billion ($A4.9 billion) in 2015. It is estimated that these payments are equivalent to 55 per cent of the total income from farming generated in the UK (NFU, 2015) each year.

What arrangements might be put in place to substitute for all or part of these payments by the UK Government in the post-EU era are very unclear. In 2014, the UK’s net contribution to the EU was £9.8bn, which is around 1.5 per cent of total UK public expenditure and equivalent to almost 0.7 per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP) (NFU, 2015). In theory, when the UK leaves the EU, these payments will no longer need to be made and therefore some of this funding could be utilised to replace existing EU CAP payments to UK farmers with equivalent farm subsidies paid for by UK taxpayers. However, in the event that the UK subsequently negotiates some form of trading agreement with the EU post-Brexit, then if the pattern established by Norway and Switzerland is applied, the UK will be required to make some contribution to the EU budget in return for specific market access arrangements. Some estimates put the potential future required contribution to the EU budget by the UK at 60 per cent of current levels. If this is the case, then the savings available to the UK Government as a consequence of Brexit may actually be less than the total current value of UK CAP payments.

The UK Government has long been a critic of the CAP, arguing that it should be transformed into some form of risk management or insurance system, rather than the current system of direct payments. If this view prevails, then it is likely that UK farm subsidy levels will be reduced in the future. This obviously has implications for UK agriculture, given that it is widely acknowledged that UK agriculture is not internationally competitive, and would decline significantly in the event that subsidies were removed. This would mean additional opportunities for competitive agricultural exporters such as Australia, although the nature of UK agricultural imports (predominantly fruit and vegetables, pork and poultry meats and wine) means that Australian would only gain small additional benefits from a reduction in UK farm subsidies.

Conclusions

The proposed exit of the UK from the EU has many uncertainties associated with it, especially in relation to the timing of the breakup, and the future UK-EU arrangements that may be put in place in advance of the split occurring. Nevertheless, it seems likely that the UK’s dependence on agricultural imports from the EU will be reduced due to likely trade barriers, and this will open up opportunities for other nations to export agricultural products to the UK. However, the UK currently accounts for only approximately 1.5 per cent of Australian agricultural exports, and it seems unlikely that even in the post-Brexit era, this will increase to any great degree.

There are, however, some wider implications of Brexit and similar protectionist and isolationist sentiments evident in the current political landscape of the USA and Europe. These suggest that the trend over the past decade of reducing international barriers for agricultural trade may have reached its limits, and that further progress in reducing global agricultural trade barriers will be difficult to achieve. For example, both main contenders in the current US Presidential contest have expressed outright opposition to the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement, indicating that the likelihood of this agreement being implemented is now remote.

For farmers in Australia and New Zealand who have long advocated for the removal of agricultural trade barriers, it may be time to take stock of the undoubted progress that has been made in recent years, and to focus on ensuring that the benefits of recently negotiated trade agreements are not eroded by the adoption of non-tariff trade restrictions. It will also be important to ensure that the protectionist and isolationist sentiments evident in these global developments do not go unchallenged.

References

Pollard, J, 2000. One Hundred Years of Australian Agriculture. Feature Article, Australian Year Book, 2000. Australian Bureau of Statistics.

DEFRA, 2015. Agriculture in the United Kingdom. Published by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Government of the United Kingdom.

NFU, 2015. UK farming’s relationship with the EU. Published by the National Farmers Union of the UK. Agriculture House, Stoneleigh Park, Stoneleigh, CV8 2TZ

Hussey, K & Tideman, C. 2013. Opportunities for Australian agriculture from an EU-Oz FTA: perceptions from Australian industry. Fenner School of Environment and Society, ANU, Canberra.

Contact details

Mick Keoghkeoghm@farminstitute.org.au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK