Supply chain evolution and the grain marketing process

Author: Brad Knight (GeoCommodities) | Date: 27 Jun 2018

Take home messages

- Narrowing, fragmented supply chains are changing the nature of price competition making the choice of where to store grain at the first point more important.

- On-farm storage profitability is very good (compared to other investments) and relatively low risk when done correctly.

- In time, on-farm grain has the potential to achieve a similar status to bulk handling grain with technological development and improved practices.

- The grain marketing process is dynamic and understanding the elements of the process helps continual improvement.

Introduction

This paper is less economic, more qualitative in regards to discussion and analysis of how the supply chain is currently evolving. Most importantly, the awareness of supply chain trends is critical to enable farmers to best position their business for grain marketing into the future. The supply chain while basic in nature is incredibly complex with lots of different stakeholders in the market. Compounding this are the numerous ‘streams’ that grain can flow down even if they are ultimately ending up in the same spot, and that each of these can often have its own supply and demand dynamics.

Supply chain trends

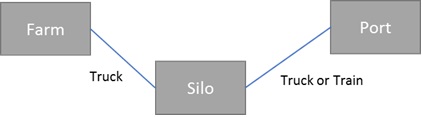

To provide context, a basic outline of the export supply chain is provided in Figure 1 which shows the links between farms, silos and export ports and the freight mechanism to transfer between each of them. Other supply chains include farm to end user (direct or via storage) and farm to packer (direct or via storage) and from the packer to port (via road or rail transport).

Figure 1. Basic export supply chain.

Supply chain efficiency is not about getting a premium but about being competitive (being able to make sales), so at any point in time you will not be able to see the difference between an inefficient and efficient supply chain. What adds complexity is that the supply chain cannot be analysed in a vacuum and there is always a complex array of supply and demand matters across each leg of the supply chain that makes analysis difficult. The timing of the pricing decisions across the supply chain are not always made in a chronological order. The following example demonstrates the extended view of the supply chain and in doing so highlights the complexities of running economic analyses on the supply chain.

Example of complexity within a supply chain

If we take for example, an end user bidding for grain and buying directly from growers at a competitive price for grain. To meet the end user’s strategy, they decide to purchase a large volume from a grain trader as they were not able to buy enough from growers at that time (the traders’ offer became cheaper than the growers’ offer). Consequently, the best bid in the market into the same destination now may be from a grain trader.

The trader buying may not necessarily be the one who has just sold, the end user may have purchased from another trader four months earlier and is now deciding to call that grain in. That trader then has the decision to execute stock they already own or buy new grain from someone else to deliver to the end user. Further to that, the trader may not actually own any stock in the right spot, and therefore, they now must determine where they can access it from? Grain stock bought for that market two months earlier may have already been used for a different order or now works better delivered somewhere else due to a change in freight spreads.

There are certainly ways that it can get even more complicated than this and grain trading is not a new process, but this example at least paints a picture of the complexity of the process and farm businesses are closer than ever before to this side of the market due to competition. Within a very simple end to end supply chain there can be many different market participants on either side of the market. Mix hundreds of these simple supply chains together and suddenly you can see why traders exist to profit from opportunities if markets move out of line with each other.

One of the main trades is price spreading between ‘track-’ (Bulk Handling Company (BCH) site grain) and ‘delivered-’ markets as each is governed by their own supply and demand fundamentals. While they are of course related to each other, it is the job of the market to ensure they do not get too far out of line in the long run. The ‘track’ market refers to grain in possession of major bulk handlers that is ticketed and when priced at port (or track level) there is a known set of gazetted location differentials (governed by Grain Trade Australia (GTA)) which are used to price that grain back to an upcountry site.

More and more grain is trading as rail site only major bulk handlers as this makes it more tradeable in terms of paper, and it is this paper trade that enables many market participants to be involved which could not exist if the crop was only traded once (from farm gate to local consumer or exporter). This competition for grain is vital to drive competitive pricing to the local site or farm gate. The downside is it complicates supply chains and does make price discovery and transacting potentially more labour intensive for the grower.

The major trend in recent years in the supply chain has been a narrowing of focus by grain buyers (exporters and traders) to be competitive in certain supply chains rather than them all. A term for this is fragmentation where there is increased competition across supply chains rather than within them. Major BHC asset holders in Victoria are increasingly competitive in their own assets rather than other traders’ assets (even though they are actively allowed to purchase in other BHCs). Further to this, there are no major bulk handling facilities or ports which are not operated by a business with a grain trading division. Those that don’t own assets are also more competitive in some supply chains than others and this trend seems to be growing as they look to remain competitive against other supply chain owners. They are increasingly looking towards farm and private networks.

As market drivers change which one is offering the best price will vary. Price competitiveness will depend on which buyer and supply chain is most aggressive at the time of sale. It is not just bulk handling assets that this applies to, but also packers and ports – this season has seen some very strong competition from several traders with container packing assets. These traders have efficiency gains through their investments and have been able to share some of this (i.e. pay growers more) to get throughput. This is a great example where competition is helping the price as without competition supply chain efficiencies are mostly kept by the innovator/investor and not passed onto the grower.

In the future, it will become a lot harder to compare ‘apples with apples’ at an aggregated level and having the right grain in the right spot will become harder to achieve as it is not always obvious which supply chain will be most competitive for certain grades and timing. To counter this, storage choices and investments by growers need to maintain as much flexibility as possible and growers should look to reduce upfront supply chain costs – once grain has started to move down a certain stream of the supply chain its costly to change its path.

Analysing on-farm storage profitability – theory and reality

There are numerous tools and resources available to help assess the economics of on-farm grain storage. One such resource is the GRDC funded Stored Grain resource. The basics of assessing on-farm storage profitability is measuring net profits per year versus initial investment (return on investment). Calculating the net profit is easy also – benefits less the costs. The costs are simple to determine as long as you don’t forget to include them all such as labour and monitoring costs (amongst others) and you must account somehow for any sunk costs (i.e. those investments already made or to be made that are required by on-farm storage, for example; augers).

The harder part of the calculation are the benefits in a financial sense of on-farm storage, as these are two-fold, cost savings and gains made (but compared to what). Furthermore, some of the savings are risk free every year (for example, freight savings, reduced ongoing carry costs of monthly warehousing) while other benefits of on-farm storage such as blending, improved segregations and avoiding quality downgrades due to speedier harvest are not guaranteed to happen every year. Anecdotally though, at least one year in three on-farm storage offers a major gain or cost saving through improved segregations (avoiding discounts at bulk handling sites) and blending opportunities.

One key message in this analysis is that any price gains post- harvest cannot be included in the economic analysis, especially when comparing on-farm storage investment to utilising bulk handling sites. This is because market improvements are felt in all storage systems if the underlying grain market improves. There may be some differences in timing and potential mismatch of grain location and demand (for example, domestic demand finds it harder to buy in BHC sites compared to on-farm) but the underlying market improvement is still felt in all systems.

Using actual data obtained from GeoCommodities between 2013 and 2018, trades of the major wheat grades ASW1, APW1 and H2 on a delivered buyer/ex-farm basis and in the bulk handling system were analysed. All sales in the bulk handling system were converted to an equivalent track price using GTA location differentials and ex-farm/delivered sales were marked to a delivered Melbourne (West side) price. All trades were collated on a monthly basis and the difference between Melbourne/Geelong track sales and delivered Melbourne prices for the same grades were compared.

The results are shown in Table 1 and while they do show some variability, overall the average price spread of $14.34 (Delivered Melbourne over track) is approaching full BHC storage and handling costs of around $17-18/metric tonne (MT). Actual road freight costs can vary around GTA location differentials but assuming they average similar to this figure of $14.34/MT, this figure can be used in working out the benefit/value of on-farm storage. Another assumption made in this analysis was track sales were averaged across all site types – rail and road only, large BHC and smaller BHC.

In reality, there is often large differences in sites depending on this rail/road status and buyer competition, so when an individual grower’s site preferences are known a similar analysis should be conducted if using the same decision-making framework.

Table 1. Delivered Melbourne versus Track Melbourne/Geelong prices for the major grades: APW1, ASW1 and H2 combined.

Season | Del Melb over Track Melb/Geel ($/MT) |

|---|---|

13/14 | 13.44 |

14/15 | 13.20 |

15/16 | 17.18 |

16/17 | 14.48 |

17/18 | 13.38 |

Overall Average | 14.34 |

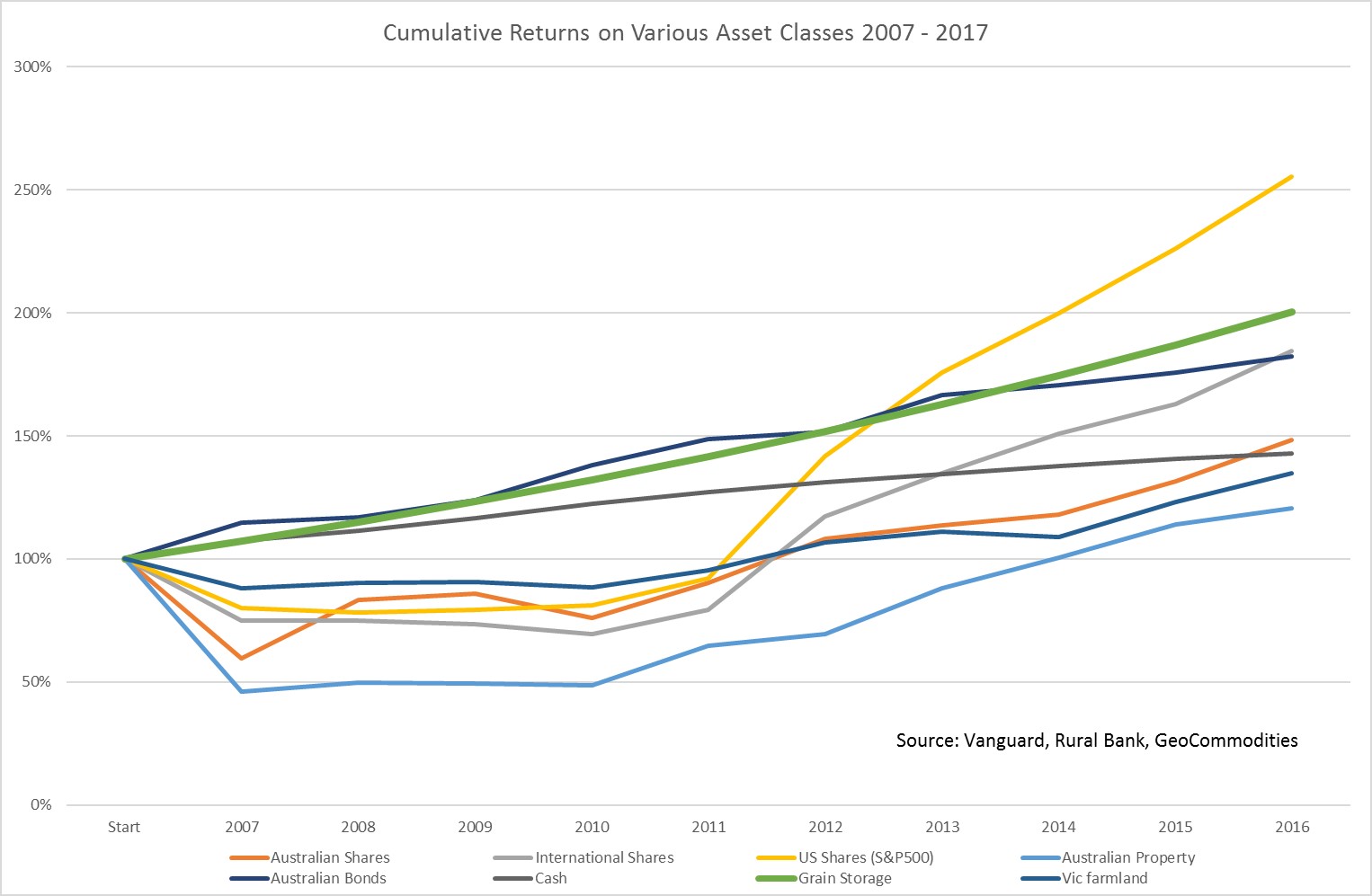

Calculation of the investment return on grain storage (Table 2, Figure 2) indicates farm storage is a very good investment. To generate an annual return, some assumptions were made around freight savings to home storage versus local BHC and a modest blending benefit (averaged out over several years across all tonnes). In terms of costs, variable costs of $3/MT (including treatment and monitoring and silo repairs and maintenance) and depreciation of $7.50/MT per year over the life of the asset. The analysis does not take into consideration tax implications (good or bad) and has deliberately left out the opportunity cost of the capital.

Table 2. Investment return of on-farm storage.

Season | All 2013-2018 ($/mt) |

|---|---|

Freight saving | 5.00 |

Blending | 2.00 |

Farm gate price vs depot price | 14.34 |

Gross Return | 21.07 |

Variable Costs | 3.00 |

Depreciation | 7.50 |

Net return | 10.57 |

Asset cost | 150.00 |

Return | 7.04% |

Figure 2 demonstrates that investment in on-farm storage compounding at around 7% per year will turn $1 in 2007 into $2 in 2017, beaten in this example only by the US share market in the same period. Australian property is well down in comparison but deserves a mention because it is a victim of the data telling a story – the years preceding 2007 had very strong growth but a correction in the housing market in 2007 saw prices drop dramatically not giving them a good start in this specific 10-year period.

Comparing returns from on-farm grain storage to other asset classes puts the investment in context and given the relatively low risk nature of on-farm storage, it compares very favourably not only against riskier assets but also conservative assets as well.

Figure 2. Cumulative returns by calendar year of different asset classes (Source: Vanguard, Rural Bank, GeoCommodities).

Weighing up on-farm storage versus bulk handler storage

While it is easy to do some basic maths, and show in theory that on-farm storage should allow some cuts in costs, it is obviously more complicated than that. One of the major stepping stones to adoption of on-farm storage is designing an on-farm strategy that dovetails in with existing fixed costs, labour and management that will be able to optimise outcomes. Further to this there are just some things that the BHC system can do better and some things grain on-farm can do better (Table 3) – note these are anecdotal guides only and vary from company to company and farm to farm.

Table 3. Performance of on-farm storage compared to bulk handling companies (BHC).

| Category | On-farm storage | Smaller BHC | Large BHC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stock swapping | Poor | Poor | Very good |

| All weather access | Average | Average | Poor |

| Carry indefinitely | Poor | Very good | Excellent |

| Hygiene credibility | Average | Good | Excellent |

| Hygiene performance | Good | Excellent | Excellent |

| Quality credibility | Average | Very good | Excellent |

| Quality control | Very good | Excellent | Excellent |

| Weekend and after hours access | Excellent | Average | Poor |

| Traceability to farm/paddock | Very good | Poor | Poor |

| Inventory finance | Poor | Average | Excellent |

To continue to take market share from BHC sites and maintain prices spreads or even drive the premium in ex-farm / delivered markets, on-farm storage needs to match BHC sites positives and think of innovative ways to deliver some of the clear benefits that BHCs have over on-farm storage.

Additionally, on-farm grain storage mustn’t do anything that loses any edge over BHC grain. Quality focus and professionalism is paramount and it is likely technology and systems are improving to help manage smaller farm based setups. Furthermore, farm businesses can have several roles in the supply chain; from seller to storage and handler and potentially logistics which can all be rolled up in one package. This can reduce flexibility at times but also provides some benefits depending on the customer.

The final comment is around future proofing the storage investment. This involves choosing the right storage for the situation and being able to have flexibility in treatment options into the future. Scrutiny on chemical usages both post and pre-harvest is going to increase rather than decrease. For example, the ever-improving maximum residue level (MRL) detection equipment and pre-harvest chemical applications. This is also not about getting a premium, it’s about avoiding a discount or finding a market in the long run. Customers assume that food and feedstuffs are safe as baseline, and it’s the definition of safe that continues to change.

Key aspects of the grain marketing process and important considerations

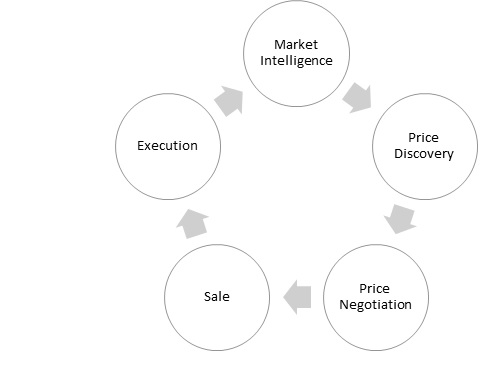

Figure 3 outlines a simple model for the grain market process. The most important feature is that it is a dynamic process that continues to develop and never ends; as one deal closes and another one opens.

Figure 3. Simple diagram of the grain marketing process.

Market intelligence

Market intelligence refers to the concept of establishing whether the present is the time to ‘play the game’ or not, depending on where the market has come from and the view looking forward. By researching the market and gathering intel a decision is being made about whether the current market situation is the right one to act in.

Further to this, it must be assumed that the market is efficient in that everything that is known today is priced into the market. This is especially important for the main commodities like cereals and oilseeds where very liquid global futures markets trade daily and give markets their lead.

There’s no beating the market by knowing information it doesn’t so the next option in market intel is gathering appropriate content from consistent sources. Appropriate meaning the information has enough depth to suit requirements and matches the timeframe in which a selling decision needs to be made. Limited information in the right context is much more valuable than lots of information that might be out of context.

Finally, understand the difference between local and offshore market influences and don’t mix them up. Occasionally, local Australian price drivers will be impacting global values as Australia is a major exporter of wheat but in most cases local and offshore factors move independently of one another so both need to be monitored

Price discovery

Once the decision to ‘play the game’ has been made, gathering information about what prices are available is the next step. Growers have never been better informed of market and price data than now with technology continuing to improve this. Market reports, online market places, social media and live pricing is increasing the accessibility of trade data. Technology will continue to revolutionise price understanding and reduce the variability in pricing day to day between different market participants.

The latter is very important to consider, as trade data showing grade, tonnes and price doesn’t always tell the full story and there will still be some variability in pricing due to the terms of the deal (payment terms is a good example). Further to this, as markets become more live they will be more responsive to changes in other markets day to day (for example, the FX markets and intra day offshore markets), so trade prices within a day could vary.

A trait of successful grain sellers is that they worry more about if selling is the right thing to do based on information available at the time (market intel), rather than the exact price achieved.

Price negotiation

Central to improvements in price discovery is the concept of bid and offer. Traditionally grain growers have been used to seeing the bid side of the market and seeking out the best bid each day. On the opposite side of the market is the offer side, which relates to what someone is willing to sell at. Quite often it is the grain sellers meeting the bid with their offer but as technology and price transparency has improved, more sellers are able to approach the market from the offer side and increasingly buyers are accepting of this practice.

This practice does push more responsibility back onto the seller, to do good market research and price discovery to know where to place the offer. However, it does have the rewards of achieving prices above bids. Further to this, understanding market sentiment becomes much more important because knowing when to hit a bid or offer at a higher price is important if the market is moving in a certain direction (i.e. in a falling market selling at the bid is often a better result than offering above and not getting a trade, only to see prices continue to weaken through the day or next day).

Market behaviour is changing more for grain in bulk handlers and differently due to the nature of how it is evolving for grain on-farm or even in private storages. Here the negotiations become as much about terms and quality of execution. The buyer wants a relationship of this nature more than a price. They want the benefits of flexible storage, accessibility or specific quality control that may only be available from smaller segregated storages.

The demand for farm grain versus BHC grain can be inconsistent due to the fluid nature of the underlying markets. Sometimes in the BHC system it is advantageous for the buyer to be able to separate the pricing and execution functions. Negotiating with a storage and logistics provider who also happens to be the owner of the grain can sometimes complicate negotiations and reduce execution flexibility for the buyer. Over time it is likely that products and technology will be developed that may enable these functions to be more separated even for on-farm grain.

Sale

Offer, acceptance and consideration– that’s all it takes to make a sale! These three components form the basis of a contract. Naturally there is a lot more to selling grain than this though. The overarching component missing from this classic contract law statement is terms.

The consideration (price) for a certain quality (bin grade) is the main focus of many market participants market intel gathering, but there are many more important aspects of the terms which must be considered and put into context around price and quality. The main additional components of the terms other than price are tonnes, bin grade and quality, location and delivery period. Other components include payment terms, carry’s, tolerance, conveyance (buyers/sellers call/option) and contract terms and conditions governing the trade. It is only once all terms are agreed upon that price can actually be negotiated.

Once the key components of any contract are agreed upon it is vital to check documentation associated with the sale. This includes the contract itself to make sure all is as agreed and then any associated documentation.

Execution

As the line between trader, grower and supply chain narrows so does the responsibility of seller and buyer to act in terms of reference of the trade. Contracts written often include a clause that states a specific tonnage and tolerance percentage, and delivery at a time nominated by the buyer (buyers call). This is done to assist buyers; however, they are difficult for growers to adhere to. Buyers are increasingly holding growers to contractual obligations.

Useful resources

- The cost of Australia's bulk grain export supply chains full report

- GRDC Update Paper: Grain storage get the system and the economics right

- Asset Class Tool

- 2017 Australian Farmland Values

Contact details

Brad Knight

GeoCommodities

bknight@geocommodities.com.au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK