Density and nitrogen timing effects on productivity of early sown wheat in Western Australia

Author: Zaicou-Kunesch, C; Curry, J; Shackley, B and Trainor, G | Date: 26 Feb 2019

Key Messages

- Four field trials in 2018 assessed the influence of plant density, nitrogen timing and grazing on yield and quality of three long maturing wheat varieties sown early April in Western Australia.

- Based on yield, Forrest and Longsword wheat varieties are more suitable for the early sowing opportunities in April than growing a mid winter (ie EGA Wedgetail) earlier.

- If there are establishment issues sowing in early April, there is generally no penalty if establishment is down to 50 plants/m². Some varietal specific responses were observed although these responses were also driven by nitrogen timing.

- For early April sown crops, delaying nitrogen application until stem elongation improved yields at Esperance, Katanning and Yuna.

- Grazing did reduce yields by up to 0.9t/ha depending on environment and variety choice, but could be achieved with minimal yield loss for some varieties and environments.

Aims

To test the following hypotheses:

1. Low plant density will not reduce yield of early April sown wheat

2. Delayed nitrogen application will not affect grain yield

3. Agronomy can offset yield reductions from grazing wheat sown in early April

Background

Early April sowing in Western Australia can provide opportunities for grazing and grain production. However to put this research in context, sowing crops early needs to be matched with rainfall and temperature so that maximum growth can be attained. Winter wheats have a vernalisation requirement that will delay stem elongation and head development until conditions are favourable. Grazing during tillering can delay stem elongation and flowering time and grazing after stem elongation can reduce head numbers and grain yield. These experiments evaluate how low plant density, timing of nitrogen application and grazing can affect the yield of winter and long maturing spring wheats in Western Australia.

Method

The effects of plant density, nitrogen timing, and grazing on the yield and grain quality of three long maturing wheat varieties was assessed in four experiments sown between the 10th and 13th April 2018. The experiments were located at Yuna, Muresk, Katanning and Gibson in Western Australia. The varieties tested were EGA WedgetailA, ForrestA and LongswordA (Table 1).

Table 1: Characteristics of wheat varieties included in the 2018 trials.

Variety

| Classification

| Maturity

| Maturity traits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Vernalisation | Photoperiod | BVP | |||

ForrestA | ASW | Long spring | Nil | Very high | High |

LongswordA | Feed | Fast winter | High | Nil | High |

EGA WedgetailA | APW | Mid winter | High | Nil | Very high |

There was stored moisture from summer rains (Table 2) however due to dry conditions at seeding and to ensure that germination occurred shortly after seeding, 20mm of water was applied prior to or immediately following seeding via a mobile irrigator at all locations except Gibson. At both Yuna and Muresk the irrigation was applied the day prior to seeding in a one-pass operation. 6mm applied prior to and after seeding supplying a total of 12mm.

Table 2: Rainfall (mm) for the four trial sites recorded at closest DPIRD weather stations in 2018.

Site | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Rain | Rain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Yuna | 73 | 21 | 5 | 11 | 44 | 38 | 88 | 55 | 6 | 13 | 99 | 275* |

Muresk | 89 | 11 | 1 | 7 | 47 | 53 | 98 | 91 | 9 | 31 | 102 | 355* |

Katanning | 37 | 10 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 48 | 55 | 45 | 10 | 28 | 64 | 238* |

Gibson | 5 | 117 | 26 | 3 | 23 | 47 | 47 | 139 | 48 | 26 | 148 | 333 |

*: April rain does not include irrigation at seeding but irrigation included in the GSR

The experiments consisted of small plots (10-12m long x 1.54m wide) sown in three or six banks, with three replicates per treatment. All trials were sown into canola stubble and all experiments received approximately 11N, 12K, 11P and 7S (treated with Uniform® except Yuna for which 25K was top-dressed in place of banded K) banded below the seed which was treated with Emerge®. Plant density treatments targeted an establishment of either 50 or 150 plants/m2. At the low density, 41 - 60 plants/m2 was achieved. At the higher density, 150 plants/m2 was achieved at Katanning and Gibson but only 100plants/m2 was achieved at Muresk and Yuna. Nitrogen treatments (200kg/ha urea, 46% N) were top-dressed at seeding or at Z31 for each variety. The grazed treatments were a mechanical treatment with a rotating string ‘whipper snipper’ to 10cm plant height before Z30 at Muresk, Katanning and Gibson and at Z31 at Yuna (Table 3).

Table 3 Date of grazing and post emergence nitrogen application (200kg/ha Urea)

Date of grazing | Date of post em. N (200kg/ha urea) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Location | Forrest | Longsword | EGA Wedgetail | Forrest | Longsword | EGA Wedgetail |

Yuna | 5-Jun | 20-Jun | 10-Jul | 5-Jun | 20-Jun | 10-Jul |

Muresk | 7-Jun | 15-Jun | 29-Jun | 13-Jun | 19-Jun | 14-Aug |

Katanning | 1-Jun | 29-Jun | 5-Jul | 8-Jun | 5-Jul | 10-Jul |

Gibson | 31-May | 29-Jun | 11-Jul | 7-Jun | 11-Jul | 20-Jul |

Results

Variety and grazing influenced wheat grain yield at each of the four locations in Western Australia (Table 4). There was a variety by nitrogen interactions at three of the four locations.

Table 4 Significance of variety, plant density at seeding, nitrogen timing and grazing on grain yield at four locations in 2018**.

Factor | Yuna | Muresk | Katanning | Gibson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Variety | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Density | n.s. | n.s. | 0.05 | n.s. |

Nitrogen | n.s. | n.s. | <0.001 | 0.01 |

Grazing | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

Variety.Density | 0.01 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

Variety.Nitrogen | <0.001 | 0.05 | <0.001 | n.s. |

Variety.Grazing | n.s. | 0.05 | n.s. | 0.01 |

Density.Grazing | n.s. | 0.05 | n.s. | n.s. |

Variety.Density.Nitrogen | 0.05 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

** treatment interactions with not significant difference at any site have been removed from the table.

Variety choice

At Yuna, the mid maturing winter wheat, EGA Wedgetail, had a significantly lower yield than Longsword (winter wheat) and Forrest (a long spring wheat) (Table 5). Variety choice along with sowing time are important factors to reduce frost risk in Katanning which had the lowest rainfall (238mm) of all sites. Longsword, was the lowest yielding wheat variety (0.56t/ha) at Katanning due to frost in September. At Muresk and Gibson, Longsword was the highest yielding variety, followed by EGA Wedgetail and then Forrest at Muresk; and Forrest then EGA Wedgetail at Gibson. Based on yield, Forrest and Longsword will be more suitable for the early sowing opportunities while EGA Wedgetail will produce lower yields but has flowering later than Longsword when considering frost as a risk to production.

Table 5 Main effect of variety (un-grazed) on grain yields* (t/ha) at four locations in 2018

Yield (t/ha) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Location | Forrest | Longsword | EGA Wedgetail | LSD |

Yuna | 3.06 | 3.17 | 2.35 | 0.12 |

Muresk | 3.48 | 4.38 | 3.90 | 0.17 |

Katanning | 2.02 | 0.56 | 2.10 | 0.14 |

Gibson | 4.81 | 5.05 | 4.32 | 0.21 |

*: Grain yield average of density and nitrogen treatment

Will low plant densities affect production of early sown wheat

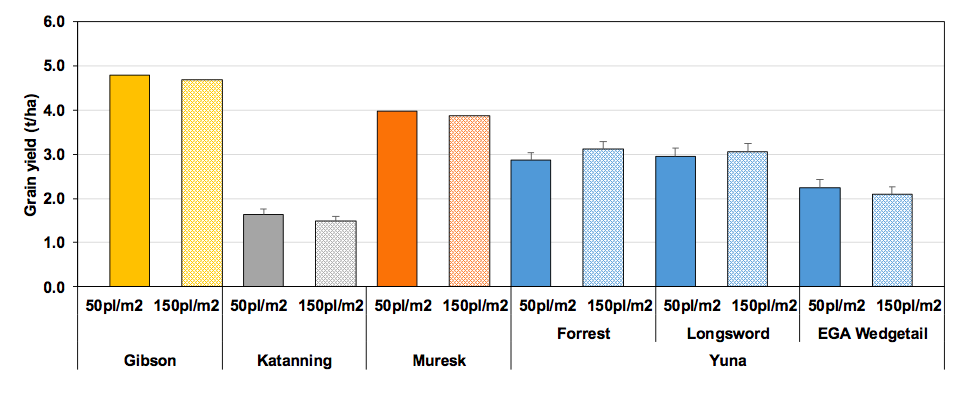

Plant density did not influence the yield of wheat sown in early April at Muresk or Esperance (Figure 1). At Katanning, yields were low due to frost and low rainfall, and there was a small but significant decline in yield at the higher plant density. At Yuna there was a variety by density by nitrogen interaction on yield. Forrest’s yields were lowest at the low density and when nitrogen was applied at seeding (averaged for grazing) (Figure 1 and 2). In contrast, EGA Wedgetail’s yields were the highest at the same density and nitrogen combination.

Figure 1 Effect of plant density on grain yield of wheat varieties at three locations in 2018

Will delayed nitrogen application affect production and quality of early sown wheat crops

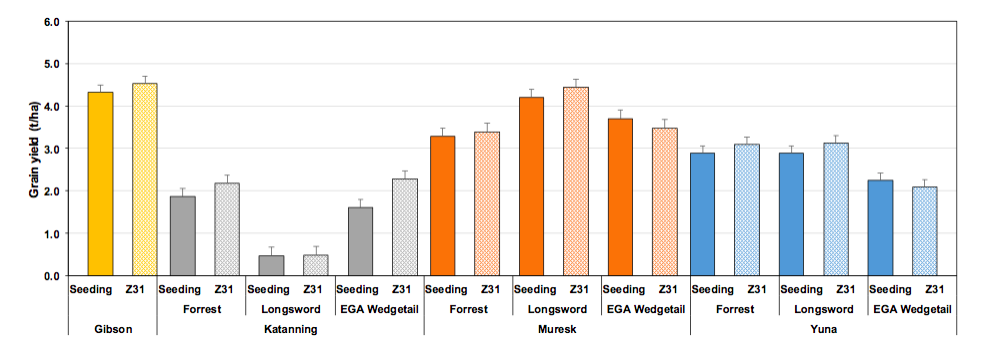

There were interactions between variety and nitrogen timing on grain yield at three of the four locations. At Yuna, there was a yield improvement with delayed nitrogen on Forrest and Longsword wheats, but not for EGA Wedgetail with nitrogen applied in late July (Figure 2). At Muresk, delayed nitrogen did not affect the yield of Forrest, increased the yield of Longsword and decreased the yield of EGA Wedgetail. A possible potassium or sulphur deficiency observed in-crop could have been a result of high rainfall and a soil pH of 4.6 at 10-20cm leading to leaching or reduced uptake. The in-crop application of sulphate of potash in August may not have been effective at improving uptake of the nitrogen for some varieties, particularly EGA Wedgetail due to the timing of nitrogen application. At Katanning, EGA Wedgetail and Forrest yields increased with the delayed nitrogen application. Longsword was frosted and there was no difference in the yield. At Esperance, yields (averaged for variety, density and grazing) improved with the delayed nitrogen until stem elongation (Figure 2). For early April sown crops, delaying nitrogen application until stem elongation is a strategy that improved yields at Esperance, Katanning and Yuna (except the frosted Longsword at Katanning or EGA Wedgetail at Yuna). Additional benefits in delaying N are probable increases in grain protein, and a better ability to match N inputs with the season’s potential.

Figure 2 Effect of nitrogen timing on wheat variety yields at four locations

Can agronomy offset yield reductions from grazing wheat sown in early April

April sowing can provide a grazing opportunity in mixed farming systems. EGA Wedgetail produce more dry matter by stem elongation than the other varieties at each locations (Table 6). The treatments were sampled at stem elongation and the trend was for an increase in biomass when nitrogen was applied at seeding for EGA Wedgetail at Yuna and Gibson, and Longsword at Gibson (Table 6). Biomass at stem elongation did not differ for the other varieties.

Table 6 Dry matter (kg/ha) at stem elongation of the wheat varieties prior to grazing at different plant densities and nitrogen application

Dry matter (kg/ha) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Location | Yuna | Muresk* | Gibson* | ||||

Variety | Urea applied Density (200kg/ha) plants/m2 | 50 pl/m2 | 150 pl/m2 | 50 pl/m2 | 150 pl/m2 | 50 pl/m2 | 150 pl/m2 |

Forrest | At Seeding | 283 | 302 | 222 | 512 | 412 | 399 |

Nil urea at sampling | 219 | 311 | 376 | 430 | 357 | 441 | |

Longsword | Seeding | 753 | 703 | 782 | 1114 | 1946 | 1734 |

Nil urea at sampling | 597 | 767 | 813 | 791 | 929 | 1217 | |

EGA Wedgetail | Seeding | 1977 | 1859 | 1019 | 1399 | 2485 | 2007 |

Nil urea at sampling | 1254 | 1616 | 892 | 1252 | 1608 | 1231 | |

LSD (V x density x N) | 93 | 12.8%CV | |||||

* Data not analysed at time of print.

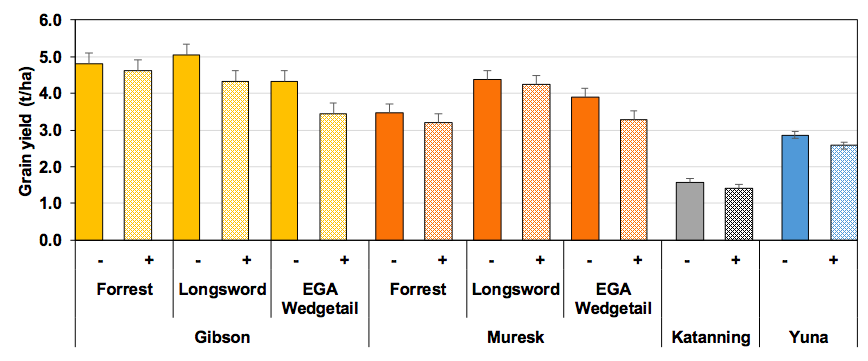

Varieties responded differently to grazing at Muresk and Esperance. At Esperance, Longsword and EGA Wedgetail yields declined significantly (0.73t/ha and 0.89 t/ha respectively) following grazing, but grazing did not affect the yield of Forrest (Figure 3). At Muresk EGA Wedgetail and Forrest yields declined by 0.62t/ha and 0.28t/ha respectively following grazing but grazing did not significantly affect Longsword yields (Figure 3).

There was no variety by grazing interaction on yield at Katanning and Yuna. However, the main effect of grazing at Z31 was a yield reduction of 0.29t/ha to 2.57t/ha at Yuna (average for variety, nitrogen and density). At Katanning the main effect of grazing was a yield reduction of 0.16t/ha to 1.4t/ha when grazing occurred before stem elongation, however the frost occurred at the site which influenced yields of Longsword.

Higher densities did offset yield reductions from grazing at Muresk but not the other locations. A low plant densities (averaged across variety and nitrogen treatment), yields declined by 0.5t/ha from 3.98t/ha in the un-grazed treatment to 3.48t/ha in the grazed treatment. In comparison, at high plant density, yields declined by 0.19t/ha from 3.86t/ha in the un-grazed treatments to 3.67t/ha in the grazed treatments.

Figure 3 Effect of grazing (-:ungrazed and +: grazed) on grain yield of wheat varieties sown in 2018.

Conclusion

Some growers seed wheat in early April following late March and early April rainfall events. There can be risks of crop failure if moisture and heat stress affects establishment and growth or weeds are not adequately controlled. Research into early April sowing opportunities in Western Australia have focused on variety selection. There is still a need for high yielding wheat varieties for early sowing and sowing wheat at the right time is one of the most important means of maximising grain yield (Shackley etal 2019, Hunt etal 2015). However early sowing with a low cost agronomy package could provide an opportunity to increase production however rotation choices, weed management and erosion risks need to be considered. Studies assessing grazing in Western Australia have focused on the southern districts with May sown crops (Curtis and Whissen 2014).

Four field trials in 2018 assessed the influence of plant density, nitrogen timing and grazing, on the yield and quality of three long maturing wheat varieties sown in the 2nd week of April 2018. The experiments were located at Yuna, Muresk, Katanning and Gibson. This research follows on from similar studies on the east coast (led by Dr James Hunt, La Trobe University). Based on yield, Forrest and Longsword wheat varieties are more suitable for the early sowing opportunities in April than growing a mid winter (ie EGA Wedgetail) earlier. If there are establishment issues sowing in early April, there is generally no penalty if establishment is down to 50 plants/m². Some varietal specific responses were observed although these responses were also driven by nitrogen timing. For early April sown crops, delaying nitrogen application until stem elongation improved yields at Esperance, Katanning and Yuna. Grazing did reduce yields by up to 0.9t/ha depending on environment and variety choice, but could be achieved with minimal yield loss for some varieties and environments. Appropriate variety choice for the environment is more important than the plant density or nitrogen timing strategies tested.

References

Curtin S. and Whissen B. (2014) Delaying wheat flowering time through grazing to avoid frost damage (Part 1: Time of cutting) Crop Updates 2014 Perth,

Hunt J., Fletcher A., Trevaskis B., Byrne J., Rheinheimer B., Devlin R., Jenkinson R. and Lamond M. (2015) Opportunities for early sowing of wheat in WA. Crop Updates 2015 Perth

Shackley B., Zaicou-Kunesch C., Curry J. and Nicol D. (2019) Which wheats for when? GRDC Research Updates 2019, Perth.

Acknowledgments

The research undertaken as part of this project is possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and GRDC investment. The author would like to thank them for their continued support. The research is co-funded with DPRID. Sincere thanks to the Brooks family and Muresk Institute for the provision of land and irrigation water at Yuna and Muresk respectively. Also to the Geraldton, Northam, Katanning and Esperance Field Support Units for the management of trials and to Melanie Kupsch, Bruce Haig, Rod Bowey and Helen Cooper for technical support.

GRDC Project Number: DAW00249 - Tactical wheat agronomy for the west

GRDC Project Code: DAW00249,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK