Earning community trust in agriculture

Author: Deanna Lush (AgCommunicators) | Date: 12 Feb 2019

Take home messages

- A farmer’s freedom to operate is enabled by an industry’s social licence, defined as the privilege of operating with minimal formalised restrictions based on maintaining community trust.

- Shared values are three to five times more important than demonstrated technical ability or science in building trust.

- An individual’s level of trust is determined by three things – influential others, competence and confidence (values).

- Transparency is a basic consumer expectation and essential in building trust with those who are sceptical of the motives and practices of the food and agriculture industry.

- The agriculture sector must upskill farmers in engagement and leading with shared values to build trust rather than providing more science and data which, while important, will not win the hearts and minds of the general public.

Background

Social licence, right-to-farm, freedom to operate, trust in agriculture — it goes by many names, but at its centre is a group of Australians who are uncertain whether they can still trust farmers to produce food in a way that is best for people, animals and the planet.

My first encounter with efforts to build trust in agriculture was in 2011 when I won a scholarship to attend the International Federation of Agricultural Journalists annual conference in Ontario, Canada. At that event, I was introduced to the work of Farm & Food Care (FFC) — an agricultural outreach organisation with a mandate to provide credible information on food and farming and to introduce the people producing their nation’s food.

After following FFC’s work for five years, and similar organisations such as the US Center for Food Integrity (US CFI), Animal Ag Alliance, US Farmers and Ranchers Alliance and the American Farm Bureau Federation, I was fortunate to receive a Churchill Fellowship to research how to build trust in agriculture. This enabled me to travel through the US, UK and Canada, in 2017 to speak with 47 organisations with activity in the area.

Through the Churchill experience, I found Australia to be lagging behind its international counterparts in five core areas:

- The understanding across the industry of the need to build public trust and the risks to industry of not planning ahead and being proactive.

- Establishing industry-supported organisations with the sole role of building public trust and engagement in agriculture.

- Developing a national strategy and steering committee in which stakeholders in the food system determine where and how to engage in trust-building activities and learn lessons from each other in the strategies that are most successful.

- Building and supporting industry voices through training and provision of strategies and tactics to help them engage with consumers on the industry’s behalf.

- Adequately funding efforts to build trust and ensuring that the level of funding matches the risk to industry if trust is lost.

My full Churchill Report is available on the Churchill Trust website. This paper is based on my winning the Australian Farm Institute John Ralph Essay, published in late 2018, named ‘The right to farm versus the right to choose: society is having the final say’. The full version is available from the AFI website.

Discussion

The Australian agricultural industry has long grappled with its right to farm. The agriculture sector as a whole is pushing back against a plethora of issues. Mining companies want access to high value agricultural land, activists do not want animals to be used for any purpose (least of all agriculture), the urban sprawl of cities is pushing into traditional farming lands, and bureaucratic pushes to change legislation or impose regulation can make it harder to farm in the way which best suits farmers.

The experience of these issues, or similar, is making farmers feel marginalised. They are farmers all day, every day for 365 days of the year. They have no control over how much money they make due to the variability of the seasons, and then they are often criticised for how they farm by people who have limited experience of the industry. It is understandable farmers might feel angry, frustrated or even not proud about what they do.

Farmers feel the impacts of an industry that is misunderstood through increases in regulation. Unnecessary regulation affects competitiveness, which then affects profitability. If farmers are not profitable, then they are not going to continue farming, which means not feeding people, not contributing to the nation’s economy nor supporting rural and regional communities. This trend is not unique to Australia and similar problems are faced in many nations overseas. The resourcefulness of farmers is to be admired — they tend to put their heads down and get on with the job, rarely complaining or seeking accolades. At the same time, they do not talk enough about what they do. As city dwellers have increasingly outsourced food production, they have become far removed from agriculture and are largely unaware about common farm practices and what is important to the food production system. Incorrect perceptions are compounded by misinformation campaigns on many aspects of food production by activism organisations.

With an increasing gap between city and country and increasing scrutiny of farming, it is not a question of whether society should determine the right to farm — society is alreadydetermining

the right to farm. The agriculture industry needs to realise the major role society is playing, accept that this reality is not going away, and then understand how to work with and take advantage of the situation, if and where possible.

This essay draws on the findings of my Churchill Fellowship report into this topic, published early in 2018 following travel to the US, UK and Canada, and further learnings acquired since its publication. I have had the opportunity to discuss these issues with numerous commodity groups, government representatives and businesses in Australia and to gather a broad overview while chairing a National Farmers’ Federation Committee working to develop a cross-commodity approach to trust in agriculture.

It’s a matter of trust

The right to farm focuses on the ability of farmers to undertake lawful agricultural practices without conflict or interference, but how do farmers obtain that right and maintain it?

At the heart of this issue is farmers’ freedom to operate, defined by the United States Center for Food Integrity (US CFI) as the ability for farmers to do what they do best with minimal outside interference (US CFI, 2017). This is enabled by an industry’s social licence, defined as the privilege of operating with minimal formalised restrictions based on maintaining public trust. So when the issue is stripped back to its core, the right to farm is tied to social licence and building and maintaining community trust.

Trust is the issue of 2018. It is an issue for churches, finance and banking entities, schools and community organisations – many institutions and industries are grappling with how to build trust, or if they have eroded trust, how to rebuild it. Roy Morgan Australia Chief Executive Officer Michele

Levine has said: “Trust requires a leadership to embrace and exhibit ethics … not just to plan how to behave, but to believe it. Deeply.” (AICD, 2018).

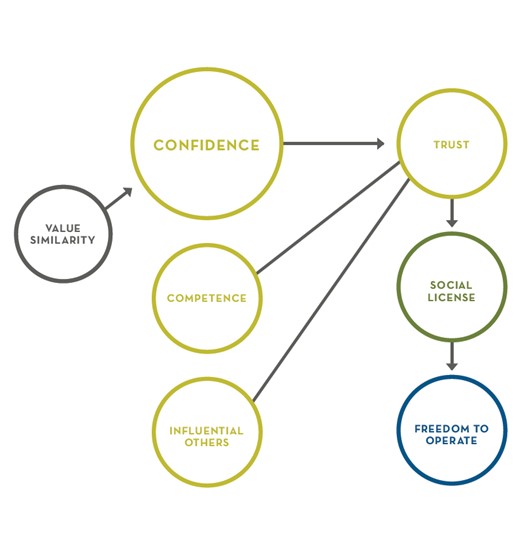

The CFI’s peer-reviewed model (US CFI, 2017), first published in the December 2009 edition of the journal Rural Sociology (Figure 1), found that an individual’s level of trust is determined by three things:

- Influential others, meaning the opinions of those in two circles – family, friends and social circles as well as credentialled others such as doctors, dietitians or veterinarians.

- Competence, which relates to science and technical capacity.

- Confidence or the perception of shared values.

Figure 1. The research-based ‘Trust Model’ developed by the US Center for Food Integrity and Iowa State University.

After surveying 6000 US consumers over three years, the CFI found shared values are three to five times more important than demonstrated technical ability or science in building trust (US CFI, 2017). Traditionally, Australian agriculture’s approach to building trust has been embedded in science and data, that is, “give people more science and data and they will come to our side of the argument”. But if they do not, we give them more research, more science and the cycle repeats. The equation of ‘science and data’ as the priority has been backwards for years because what consumers really want to know is “Can I still count on you to do what is right”.

CFI research has found that to build trust, the industry needs to lead with shared values. Many consumer questions are based on whether practices are ethically grounded (Figure 2) and so based on values such as compassion, responsibility, respect, fairness and truth (Arnot, 2018). Traditional approaches to building trust have given people information about science and economics to increase their knowledge, but have done little to influence how they feel and what they believe. The CFI believes that is where a better connection needs to be made. The debate is not focused on knowledge but rather “whether we should be doing what we’re doing”, which is a conversation about values and ethics.

The US experience is that the ‘shared values’ approach helps farmers respond in a strategic way, rather than visceral (Arnot, 2018). The key lies in giving farmers the tools for that values-based communication and then supporting them in that journey, building their skills and

confidence. The CFI observes that the community likes farmers, but they are not sure they like farming or industry. Farmers who become engaged in leading with shared values feel empowered because they are able to be part of the dialogue.

Figure 2. Value similarity – how feelings and beliefs through ethics contribute to sustainable systems, developed by the US CFI.

The international context

Internationally, there is significantly more work being undertaken to protect the right of farmers to farm through building trust and relationships with non-ag audiences than there is currently in Australia. Canada has value chain roundtables for all its agricultural commodities, where stakeholders meet regularly to discuss a range of issues, such as trade or food safety. Trust in agriculture has been added to these roundtable discussions to keep the issue front of mind for all stakeholders and to chart a way forward in building and maintaining trust.

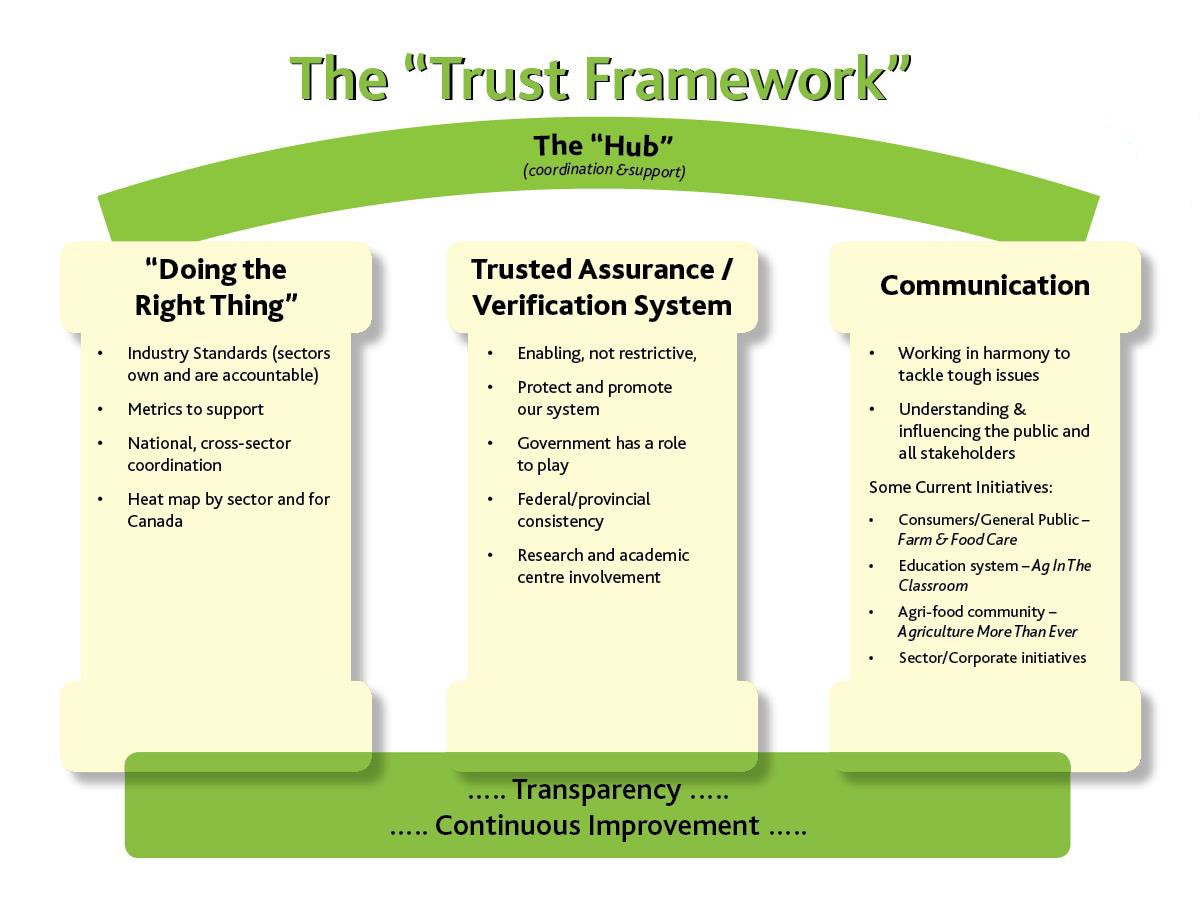

The Canadian Centre for Food Integrity and its partners are pioneering the concept of ’the journey to build public trust’. Chair Kim McConnell says it is a long-term project, but the framework is simple, describing it as a house with three pillars, two foundations and one roof (Figure 3).

The three pillars are:

- Do the right thing. This involves all the players along the value chain agreeing what the right thing to do is, and then putting a procedure in place to ensure all participants abide by it.

- Develop a trusted assurance system. Listen to what the consumer thinks is important and put in place national certifications. Ensure the government, research and academics all fill their roles.

- Communicate it. Put a communications system in place that involves everybody – individuals, corporations and associations. McConnell says a particular industry talking about how great it is does not have much credibility, which is where cross-commodity advocacy organisations fit it well because they speak more on behalf of the industry to the public and all stakeholders and add credibility.

The two foundations are:

- Transparency.

- Continuous improvement.

The roof, or hub, is:

- Learn from one another and provide coordination and support. What lessons can be learnt from other industries? What lessons can the beef industry’s approach to public trust hold for the grains or seafood industries, and vice versa? There are likely to be some similarities and differences that are worth discussing.

Figure 3. The Trust Framework adopted by the Canadian Public Trust Steering Committee.

McConnell says Canada is striving for a system that says ‘we’re efficient, we’re sustainable and we take great care in what we’re doing’. He believes there must be substance to the claim so that farmers can say it with confidence.

In 2018, many of the roundtables established sub-committees to specifically carry forward actions in building trust. Canada is supporting a National Manager for its trust-building process, who is working between all the industries and organisations to share knowledge and insights into what is working across sectors (Grahn, 2018). In Australia, the discussion about the importance of food production can often be one-sided and attempted in a very reactive state, such as following an announcement of a policy that is anti-agriculture or launch of a new activism campaign. In contrast, the US Farmers and Ranchers Alliance (USFRA) is focused on fostering a two-way exchange. Former CEO Randy Krotz said one of the USFRA’s most successful initiatives had been to change the language and the tone of the discussion to make it a dialogue instead of a one-way conversation (2017). He described the USFRA’s ‘Conversation Movement’:

“Consumers are having conversations about food production, but the voices of farmers and ranchers are frequently left out of the discussion. By creating a dialogue with consumers, farmers and ranchers have an opportunity to teach consumers about how food is grown and raised. Why is this important? The people producing the food are the most qualified to tell the story. Through engagement and conversation, farmers and ranchers can reach customers with stories and data that illustrate modern agriculture, continuous production and business improvements. In the end, we are all united by our compassion and love of food and land.”

One of the recommendations of my Churchill Fellowship report is that the industry needs a national network of well trained and prepared spokespeople across all agricultural commodities (Lush, 2018). Investing in building credible spokespeople and equipping them with the knowledge of how to engage with non-agricultural audiences is one of the most immediate ways organisations can act to build trust. Training needs to go beyond one-day media training workshops to engage our current and future spokespeople in a more meaningful and long-term way, using shared values as the foundation. All people in agriculture have networks in both agricultural and non-agricultural areas, so if building trust starts with relationship and shared values, then this is low-hanging fruit for the entire industry.

Farmers mustbe part of the conversation. When they are not, that is where many of the sector’s issues originate. Agriculture is not well understood outside its own echo chamber and everyone in the industry needs to deeply consider the role they can play in bridging the rural-urban divide. US CFI CEO Charlie Arnot says that if we are not in the conversation, we should assume that another perspective will prevail (US CFI, 2017).

It’s about transparency

The right to farm argument all boils down to trust. Consumers are asking farmers — “Can I rely on you to do what is right?”

In his recent book, Size matters: why we love to hate big food (2018), Charlie Arnot outlines that the food system – which clearly includes farmers – must bear its share of responsibility for the current lack of consumer trust. For society to be accepting of potential changes that could improve diets, health and sustainability, the food system must be transparent and consistently worthy of trust.

Transparency is no longer optional, it is now a basic consumer expectation and essential in building trust with those who are sceptical of the motives and practices of the food sector (Arnot, 2018). Transparency is the best way for farmers, food companies, restaurants and retailers to demonstrate they share consumer values on important issues such as food safety, the impact of diet on health, animal care and protecting the environment. Trust generated by transparency will provide farmers, food companies, restaurants and retailers with the social licence needed to succeed in times of both calm and crisis. According to the US CFI (2017), a commitment to greater transparency includes considering:

- Motivations — acting ethically.

- Disclosure — openly sharing good information and bad.

- Stakeholder participation — engaging and being responsive.

- Relevance — providing information that stakeholders care about.

- Clarity — providing information that is easy to understand.

- Credibility — a record of operating with integrity.

- Accuracy — be truthful, reliable and complete.

Research into the drivers of trust and distrust in Australia support these CFI findings. Trust in 2018 is driven by good customer service, honesty, ethical behaviour/integrity, reliability, transparency, social conscience, quality, long history and customer focus. Distrust is driven by greed, self-interest, putting profits before customers, deceit, and unethical behaviour (AICD, 2018).

Arnot says transparency can be terrifying or liberating, depending on your perspective. Farmers and industry may be in for a rude shock if they hope that no-one will discover what is really going on behind the farm gate. The current era of radical transparency means everyone with a mobile phone can publish video on social media. On the other hand, a commitment to greater transparency to demonstrate shared values with customers and other stakeholders will be rewarded with increased trust, enhanced social licence and freedom to operate.

He warns that farmers and industry must be prepared for one of two things to happen with increased transparency. The non-agricultural community will either have a greater appreciation that practices are consistent with their values and expectations, which reinforces trust, or they will discover practices that are inconsistent with their values and demand change. In either case, transparency drives alignment of community expectations and farming practice.

US CFI conversations about transparency centre on finding out whether people want more information about policies, practices, performance or verification. Practices are a reflection of farmers’ values in action and so interest in farm practices is high. The more transparent farmers are, the more people are able to give them the benefit of the doubt. Arnot says there is always a hesitancy and sometimes farm practice is not pretty, but people understand that and do not expect perfection, they expect authenticity.

Change goes both ways

In developing a culture of trust and transparency between the farm sector and consumers, there is real possibility that, even after being open and leading with shared values, an industry might be asked to change its practices. This means a previously legal farm or industry practice is no longer considered socially acceptable. The US CFI notes it is often not a question of whether we cancontinue a certain practice – the science often says we can – the question is about whether we should. This is a reality that not all Australian industries are planning for or handling well.

In her address to the National Press Club on 29 August 2018, National Farmers’ Federation President Fiona Simson outlined the need to find a balance between production of food and fibre and right to farm issues in which decisions are underpinned by evidence-based science and sensible policy. Referencing the environmental issues which farmers are currently facing, she said that since European settlement, farmers had been managing the environment to grow food and fibre. Her observation is that the community is now moving to place some obligations on farmers – some right and true, and some not – to take areas out of production, to lock up land because the community thinks that, for example, trees are more important than grasslands and grazing stock. She compared this with a supermarket being asked to remove three aisles of its offerings, which would have a clear impact on profitability. In the same way, locking up land would suddenly impact on what farmers do. So, she argued, if the community values environmental outcomes highly then we need to start putting a price on that and consider compensating farmers in some way. At the same time though, she said where found lacking, the industry should act to improve practices to meet community standards. There is too much to lose if we do not.

Building trust versus defending an interest

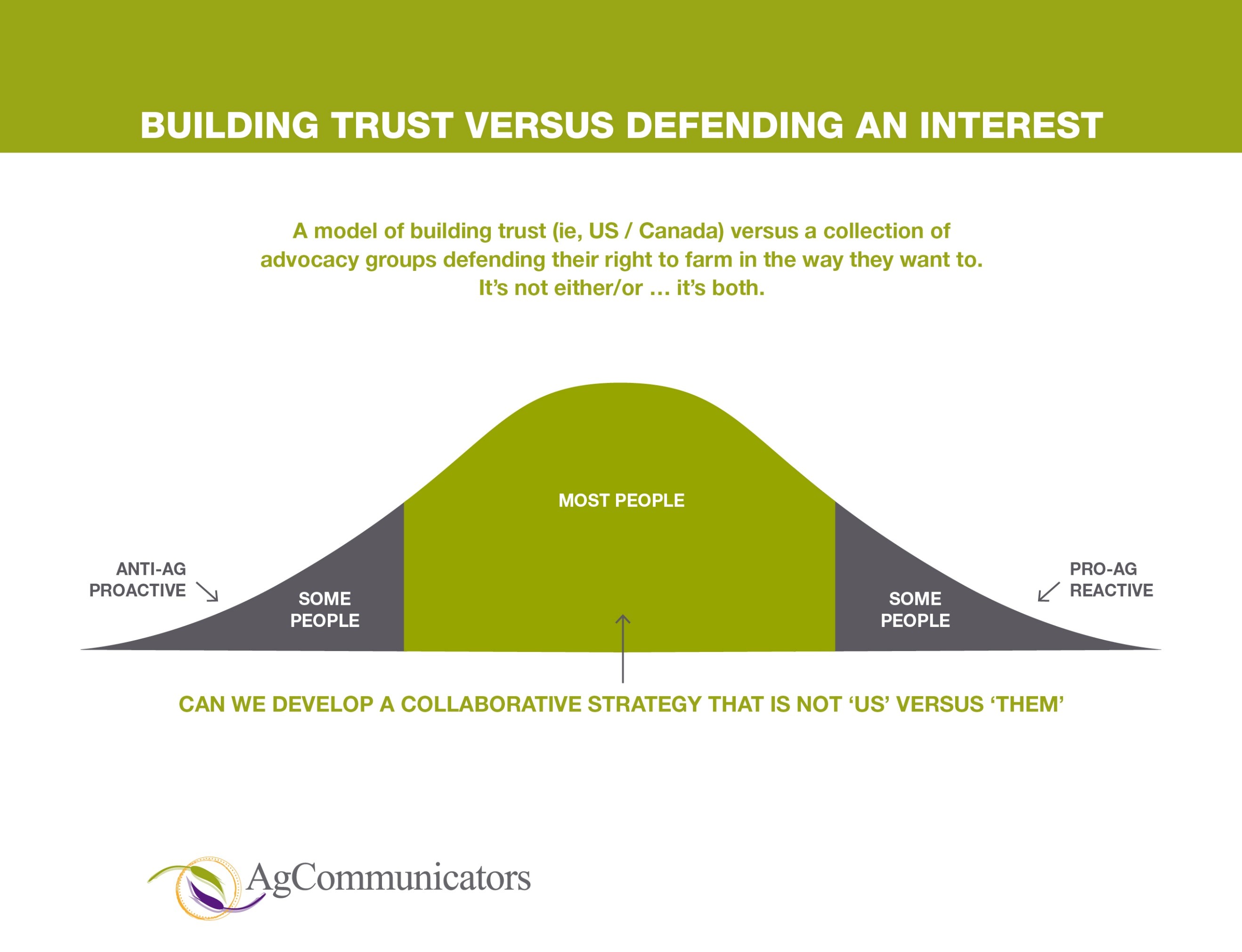

Following publication of my Churchill Fellowship, and considering the issues since, it is clear the Australian agriculture industry needs to consider where it engages in building trust. There are three distinct activities – defending an interest or a practice, general outreach/awareness and proactive trust-building strategies – the first two of which I have found are often confused for building trust (Figure 4).

Defending an interest or practice is very different to building trust. Defending an interest is lobbying

on behalf of members and advocating to politicians. Members of lobbying organisations have an expectation that those organisations will protect their interests against those who would seek to erode them. Recent examples of these issues include live export, genetically modified biotechnology, agricultural chemical use and a raft of animal husbandry practices.

Figure 4. A model which outlines the difference between defending an interest or practice and a long term commitment to build trust.

Outreach and awareness programs represent the middle ground, communicating positive ag messages or providing positive ag experiences. This is being achieved through tactical areas such as social and digital media, presence at public events, training of farmers to engage, use of earned media and influencing those who are driving conversations about food, identified through consumer sentiment research.

These first two areas are where much of the work in Australia is being undertaken. Australia has an extensive lobbying system which advocates to government and other decision-makers when right to farm issues are raised. In addition, Australia has a network of well-funded rural research and development corporations, many of which have outreach programs which promote the sustainable and ethical production of their commodity. These campaigns are separate to the marketing functions of these organisations, which seek to increase consumption of their commodity.

Building trust is a longer term, generational process. Arnot (2018) says building trust embraces the evolution of consumer expectations, access to unlimited information, demand for greater transparency and the growing interest by consumer facing brands. It is proactive, engaging and can encompass whole-of-food systems. When it engages the food system, this means it can leverage funds beyond farmer levy money – which is important in Australia given the draw on that funding source (Lush, 2018).

In the US and Canadian experiences, there was extensive activity in all three areas. Both countries have very active farm lobbies defending farmers’ interests. In addition, many of these organisations and groups focused on production have pooled their resources to create outreach and awareness programs and organisations, such as Farm and Food Care, the US Farmers and Ranchers Association and the Animal Agriculture Alliance. Then there were separate efforts focused on building trust, not defending a practice, which contributed to a balanced discussion about food and agriculture and worked to build relationships and understanding, mostly through the US CFI. Those which had pooled their resources recognised that consumers do not distinguish between beef, grain or dairy farmers – all farmers are viewed together as farmers. According to Arnot (2018), building trust requires champions who see the long-term value and understand the return on investment beyond their own organisation.

Regardless of the role each organisation might take, it is important to note there is no ‘either/or’ when it comes to defending an interest, outreach or building trust. All are needed and are valuable. There is so much work to do in building trust that it is a case of ‘every shoulder to the wheel’. The agriculture industry can spend a lot of time rebutting claims of the anti-ag lobby, or it can work together to develop a collaborative strategy that is not ‘us’ versus ‘them’ and seeks to target the silent majority, as outlined in Figure 5 (Lush, 2018). We do need to realise, however, that each approach is different and generates a different result.

Figure 5. A model which outlines the need to focus on a collaborative strategy to engage the majority, in contrast to defending the industry against anti-ag sentiment.

Conclusion

Farmers may believe they have a right to farm, but equally the market has a right not to buy their products (Arnot, 2018). Building trust is about aligning the values of food production with the values of the community, and it may require changes to industry or farm practices.

The debate over the right to farm will continue to take place on the ‘should we’ questions — what are the values, what are the ethics, should farmers and the food system be doing what they are doing? Since farmers do not have as much contact with consumers as others in the food system, an openness to the genuine questioning of their practices requires a huge mind shift. However, it is a mind shift that the industry urgently needs to tackle.

Agriculture as a whole must upskill farmers in engagement and leading with shared values to build trust rather than providing more science and data which, while important, will not win the hearts and minds of the general public.

If transparency is the key to building trust, maintaining a social licence and hence overcoming right to farm issues, we need to consider if agriculture is prepared for transparency. Are farmers and industry prepared to have the difficult conversations about potentially planning for a change in farm practices in future? Are farmers prepared to be called out by their own industry if practices do not align with community expectations, or if they breach standards that are in alignment with the community? Given the community trusts farmers and can relate to them through a values-based approach, are farmers prepared to invest their time and energy in engaging with non-ag audiences about farm practices to protect their freedom to operate?

The industry has spent enough time being caught flat-footed and defending the indefensible. It is time to look at a new approach and a new way of engaging. The sooner we recognise that society is

already deciding the right to farm and choose to be part of that conversation, having influence where we can, the better. The alternative is to stay our current course and see where the industry ends up.

Useful resources

Churchill Trust of Australia – www.churchilltrust.com.au (search for Deanna Lush under Fellows for Churchill report)

Australian Farm Institute – www.farminstitute.org.au

US Center for Food Integrity – www.foodintegrity.org

Farm and Food Care – www.farmfoodcare.org

US Farmers and Ranchers Alliance – www.fooddialogues.com

US National Corn Growers Association – www.findourcommonground.com

Animal Agriculture Alliance – www.animalagalliance.org

References

Arnot, C. 2018. An international perspective on building trust. Presentation to National Farmers’ Federation members and stakeholders, Friday 10 August 2018, Canberra, ACT.

Arnot, C. 2018. Size Matters: why we love to hate big food, Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, p. 92.

Australian Institute of Company Directors, 2018. Company Director – It’s a matter of trust. Volume 34, Issue 7, p. 20-23.

Grahn, M. 2018. Canadian Public Trust Steering Committee National Manager, personal communication, 3 August 2018, Australia.

Krotz, R. 2017. CEO, United States Farmers and Ranchers Alliance, personal communication, 16 October 2017, St Louis, United States.

Lush, D. 2018. Communication, education and engagement methods to improve understanding of agriculture, Churchill Fellowship, available online at https://www.churchilltrust.com.au/fellows/detail/4144/Deanna+Lush

Lush, D, 2018. Building trust in agriculture, Presentation to National Farmers’ Federation’s members and stakeholders, Friday 10 August 2018, Canberra, ACT.

McConnell, K. 2017. The Canadian Journey to Public Trust – update. 4 October 2017, viewed online at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56be29e022482ec146a7c5b8/t/584075a3d2b85768c5e64a4f/1480619439193/CWS-S35-McConnell.pdf

Simson, F. 2018. Address to the National Press Club, 29 August 2018. Viewed online https://iview.abc.net.au/show/national-press-club-address/series/0/video/NC1811C032S00

US Center for Food Integrity. 2017. CFI – Update, presentation and personal communication with US CFI Team during Churchill Fellowship, 18 October 2017, Kansas City, Missouri.

Contact details

Deanna Lush

AgCommunicators

99 Kensington Road, Norwood

0419 783 436

deanna.lush@agcommunicators.com.au

@deannalush

@AgCommunicators

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK