Optimised canola profitability — looking into key findings of four years of research

Author: Cameron Taylor (Birchip Cropping Group) and Rohan Brill (NSW DPI) | Date: 26 Feb 2019

Take home messages

- Selecting mid-fast canola hybrid varieties with flexible phenology in the Wimmera manages risk and captures great upside when seasonal conditions are favourable.

- Fast hybrids have performed well but avoid the temptation to plant these early if an early break eventuates.

- Selecting slow developing varieties comes with the added risk of requiring germinating rain in the first week of April or earlier in low to medium rainfall environments.

- The best return on investment in nitrogen (N) results from application to hybrids that flower at the optimum time for the environment.

Background

Understanding the phenological responses of a canola variety will guide sowing decisions to ensure flowering starts in the optimal window to maximise yield potential. Timing flowering to avoid the stresses of frost and disease (too early), and drought and heat (too late) will allow the favourable conditions required for canola to grow and produce a high yield potential. Research through the GRDC supported Optimised Canola Profitability Project (CSP00187) has been carried out in the Wimmera region from 2015 to 2018. Findings of this research, focusing on time of sowing, have shown that phenological differences are amplified when canola is sown before mid-April, meaning that there may be a matter of a few days difference in start of flowering between a fast and slow variety when sown in early May, but weeks for the same varieties sown in early April. Therefore, varieties should be chosen carefully, based on phenologyin the event of early sowing.

In 2017 and 2018, the Birchip Cropping Group (BCG) included N application rates (aimed at decile 3 and 9 seasons) to assess the response of varieties sown at different times (mid-April and early-May) This work found that open pollinated triazine tolerant (OP TT) varieties did not respond to the application of N as well as hybrid varieties due to the hybrid vigour setting more yield potential at the start of flowering (Brill and Taylor 2017).

Method

A replicated split plot design trial was sown at two times of sowing. Crop was established with drip irrigation in crop rows of 15mm on TOS 1 and 7.5mm on TOS 2 due to prior rainfall. Assessments carried out in the trial included establishment counts, normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), flowering dates, biomass at start of flowering, yield (from harvest cuts taken at varietal maturity), harvest index and grain quality. Nitrogen treatments were top-dressed as urea at either a low rate (targeting 1.4t/ha yield) or a high rate (targeting 5t/ha yield). The starting soil N was 68kg N/ha to 1m depth Nitrogen applications were applied with significant rainfall events predicted after application.

Table 1. Treatment outline in 2018 Longerenong trial Variety x Time of Sowing x Nitrogen treatment.

Variety | Phenology | Time of Sowing (TOS) | Nitrogen Application |

|---|---|---|---|

Diamond | Fast | TOS 1 (13 April) | Low rate @41.5kg urea/ha 5 June 2018 (Targeting 1.4t/ha yield) |

ATR Stingray | Fast | ||

44Y90 CL | Fast - mid | ||

ATR Bonito | Fast - mid | ||

45Y91 CL | Mid - slow | TOS 2 (8 May) | High rate @667.5kg urea/ha split application 5 June and 2 July (targeting 5t/ha yield) |

45Y25 RR | Mid - slow | ||

ATR Wahoo | Mid - slow | ||

ArcherA | Slow |

Results and discussion

2018 Wimmera trial results

Biomass

There was a general trend of greater biomass at flowering from all varieties sown on 8 May (TOS 2) compared to the 13 April sowing, except for Archer as there was a time of sowing by variety interaction (P=0.014). 45Y91 CL and 45Y25 RR, with their similar phenology, produced on average the same biomass in the respective sowing times. Diamond and ATR Stingray, also with similar phenology to each other, had a large difference in biomass at flowering, due to the hybrid vigour of Diamond. This trend was observed for 44Y90 vs. Bonito and Archer vs. Wahoo when comparing varieties with similar phenology. On average, the 8 May sowing time produced 0.7t/ha more biomass than the April sowing.

An interaction was also observed between varieties and N application rates, where all varieties showed on average greater biomass at flowering under the high N application. The high N treatments averaged 1.2t/ha more biomass at the start of flowering cutting timing. The later developing hybrid varieties 45Y91 CL, 45Y25 RR and Archer had the largest response to N and produced significantly more biomass at this timing than the other varieties in the trial (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mean of start of flowering biomass (t/ha) for varieties at different N application rates. Stats: P=0.009, LSD= 0.50 t/ha, CV 13.5%.

Yield

Yield was variable across treatments with an interaction found between varieties, time of sowing and N rate. 44Y90 CL at the early sowing topped the trial yields with 1.46t/ha, closely followed by 45Y91 CL and Diamond yielding 1.24t/ha and 1.21t/ha, respectively, all sown in the early April timing. As a fast hybrid variety, Diamond showed the most consistent yield across times of sowing and N rates (Table 2). Diamond has performed consistently well in the past three years of the trials (Table 4).

Table 2. Grain yield (t/ha) of varieties at different times of sowing (13 April, 8 May) and under different N application rates (high N, and low N) in 2018.

Variety | TOS 1 (13 April) | TOS 2 (8 May) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Low N | High N | Low N | High N | |

Diamond | 1.04 | 1.21 | 0.96 | 1.15 |

ATR Stingray | 0.64 | 0.97 | 0.85 | 0.42 |

44Y90 CL | 0.89 | 1.46 | 0.91 | 1.19 |

ATR Bonito | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.86 | 0.47 |

45Y91 CL | 0.76 | 1.24 | 0.83 | 0.35 |

45Y25 RR | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.31 |

ATR Wahoo | 0.61 | 0.27 | 0.59 | 0.16 |

Archer | 0.92 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.55 |

Sig. Diff. LSD (P=0.05) CV% | P<0.001 0.26 24.4 | |||

Research from 2017 found that OP TT varieties did not respond as well to N as hybrids (Brill and Taylor 2017). ATR Bonito and ATR Wahoo had a negative yield response to a high rate of N application in 2018, but ATR Stingray had a yield increase with a high rate of N application in the early time of sowing and a negative effect in the later sowing time. In general, TT varieties showed less of a response to N application than fast developing varieties and early sown mid developing varieties in 2018. 45Y25 RR, ATR Wahoo and Archer displayed a negative yield response to N application similar to the TT varieties.

The application of a high rate of N reduced the yield of some varieties. The effect was more evident with slower developing and OP TT varieties at the later sowing timing. This is likely due to the very high N levels causing canola to hay off in the 2018 seasonal conditions.

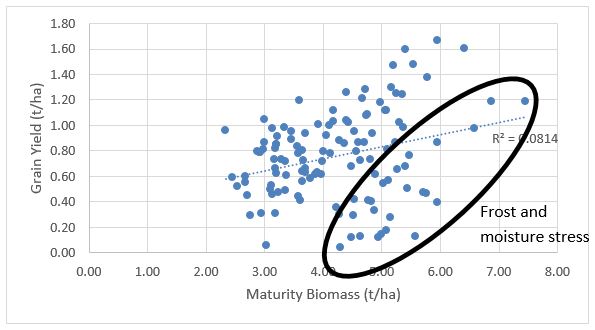

This theory is substantiated by biomass at maturity, where biomass did not always reflect final yield, unlike other seasons (Figure 2). ATR Wahoo, a later maturing variety, had greater biomass at maturity from high N application treatments, however, low N application treatments out-yielded at each time of sowing suggesting it may have hayed off early, limiting the ability to fill grain.

Figure 2. Maturity biomass (t/ha) and grain yield in 2018 at Longerenong. Black circled area represents the data points either affected by frost and/or moisture stress causing a ’haying off’effect.

Grain quality

Oil content was below 42% for all treatments with high N application reducing oil. The lowest oil content was found in the high rate of N treatments for Diamond and ATR Wahoo (Table 2). This is an expected trend as high N is known to have a negative impact on oil content (O’Brian and Street, 2017). All test weights were within the acceptable range for canola. ATR Stingray consistently averaged the highest test weight between times of sowing and N application rates.

Table 3. 2018 Longerenong Canola Phenology Trial: Mean oil (%) of varieties at different sowing times (15 April and 8 May) and under different N application rates (target decile 3 & 9).

Variety | TOS 1 (13 April) | TOS 2 (8 May) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Low N | High N | Low N | High N | |

Diamond | 40.9 | 34.4 | 38.9 | 33.1 |

ATR Stingray | 37.2 | 36.5 | 39.9 | 35.8 |

44Y90 CL | 40.7 | 37.7 | 41.2 | 39.0 |

ATR Bonito | 41.0 | 36.3 | 38.9 | 36.8 |

45Y91 CL | 40.2 | 36.6 | 39.7 | 38.5 |

45Y25 RR | 38.9 | 36.2 | 40.7 | 37.2 |

ATR Wahoo | 38.3 | 35.9 | 38.6 | 36.8 |

Archer | 40.1 | 34.5 | 38.6 | 33.5 |

Sig. Diff. LSD (P=0.05) CV% | P=0.016 1.8 3.2 | |||

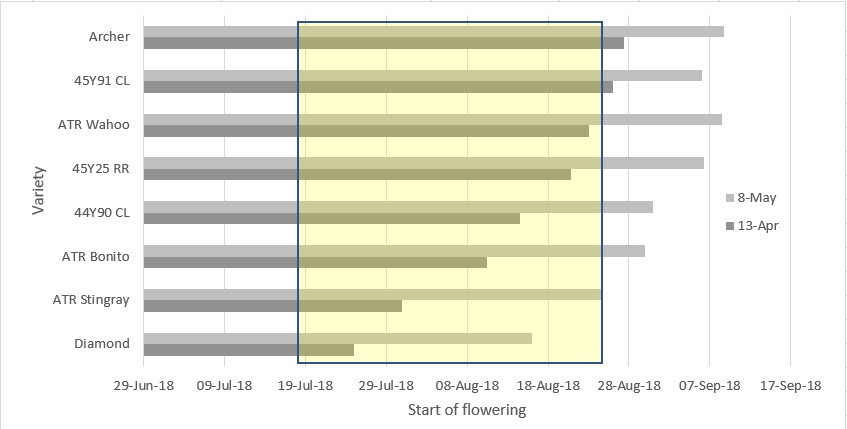

Start of flowering windows

Diamond, an early maturing variety, was the first to begin flowering in both times of sowing with both flowering within the optimal start of the flowering (OSF) window for Horsham (18 July-25 August). There was a trend towards a decrease in yield when flowering was not reached by the end of the OSF on 25 August. Sowing on 8 May (TOS 2) was too late for the majority of treatments to begin flowering within the OSF window, driven by maturity (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Canola phenology trial at Longerenong time of sowing effect on the start of flowering date. Start of flowering optimal window for Horsham highlighted.

Earlier sown varieties flowered earlier and averaged a higher grain yield. When the OSF date had passed, there was a general decrease in yield observed for all herbicide tolerant groups. It is important to note frost data has not been taken into account to quantify the contribution to yield losses.

Conclusion

Overall canola production 2015-2018 in the Wimmera

Growing canola in the Wimmera over the past four seasons has been highly variable with considerable risk. Wimmera canola phenology trials have averaged 2.0t/ha (Table 3). The findings from the trials have indicated that with good variety choice, N management and by taking early sowing opportunities to match the varieties’ optimal phenology windows, the risk of variations in the seasons can be managed, with a maximum upside of 2.77t/ha average over the four years.

Table 4. Summary of rainfall, average biomass and yield production from2015-2018 canola phenology data in the Wimmera.

Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Previous crop type | Wheat | Faba Bean | Lentil | Barley |

Rainfall (Nov-Oct) | 228 | 467 | 424 | 284 |

Rainfall (Apr-Oct) | 125 | 374 | 303 | 187 |

Biomass 50% flower initiation (t/ha) | 1.62 | 4.13 | 4.83 | 3.7 |

Biomass maturity (including grain) (t/ha) | 2.08 | 11.85 | 11.70 | 5.01 |

Yield (t/ha) | 0.12 | 3.46 | 3.83 | 0.75 |

Harvest index | 0.06 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.15 |

Variety selection based on yield

The past two years of trial work at Longerenong, have suggested that fast to mid-fast sown hybrid varieties have proven to be consistent high performers. Hybrid varieties have been out-performing OP varieties consistently through the years when comparing amongst phenology groups (Table 4). When considering a long season canola in the Wimmera, germination early (first week of April) in the season is required to ensure the greatest chance of profitability. Considering the increased cost of holding a long season canola variety and relying on a germinating rain in early April, there may not be an opportunity to access seed and sow in a timely fashion. Selection of a variety such as 44Y90 CL with flexible phenology (slows from early sowing but speeds up with late sowing) will help capitalise on early breaks, while also yielding well in later starts.

Table 5. Yield by time of sowing from 2017-18 Longerenong trials presented as a percentage of the mean.

Breeding Method | Phenology | Variety | 2017 (3.82) | 2018 (0.75) | Average (2.29) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

TOS 1 | TOS 2 | TOS 1 | TOS 2 | TOS 1 | TOS 2 | |||

Hybrid | Fast | Diamond | 108 | 106 | 150 | 141 | 129 | 123 |

Open pollinated | Fast | ATR Stingray | 92 | 95 | 107 | 84 | 99 | 89 |

Hybrid | Mid-fast | 44Y90 CL | 104 | 107 | 161 | 140 | 132 | 123 |

Open pollinated | Mid-fast | ATR Bonito | 90 | 91 | 68 | 88 | 79 | 90 |

Hybrid | Mid-slow | 45Y25 RR | 108 | 106 | 92 | 59 | 100 | 83 |

Open pollinated | Mid-slow | ATR Wahoo | 99 | 91 | 59 | 49 | 79 | 70 |

Hybrid | Slow | Archer | 101 | 97 | 105 | 82 | 103 | 90 |

Nitrogen application

When applying N to canola, the rule of thumb has been to supply 80kg/ha of N (between soil, fertiliser and mineralisation) for one tonne of grain yield potential. The previous two seasons have seen positive responses to biomass when applying high levels of N to fast to mid-fast developing varieties, which translated into higher yields. Key growth stages to assess the canola’s potential yield are at the start of flowering and maturity. At the start of flowering 4t/ha of canola biomass needs to be reached to have maximum yield potential (Figure 5). If the canola dry biomass was less than 4t/ha at the start of flowering, then the maximum yield potential was limited and N applications from this point should be adjusted to reflect a lower potential if the season looks favourable for high yields (Figure 5). At maturity (windrowing time), the biomass (less the grain weight) has needed to be at least 8t/ha to achieve the maximum yield (Figure 5). When choosing a variety with fast development, it is important not to sow too early (start of April) as it will not have enough time to accumulate biomass if trying to achieve a high yield potential. This is the reason why hybrid varieties can set higher yield potential than OP TT varieties in the experiments.

Figure 4. Start of flowering biomass and maturity biomass (t/ha) vs. grain yield (t/ha) for all Wimmera phenology trials 2015 to 2018.

In 2017, it was observed that hybrid varieties were better able to capture a higher yield potential when larger rates of N were applied compared to OP TT varieties. In 2018, higher biomass was achieved in all varieties when N was applied, but the high N treatments had a ’haying off’ effect on yield in the slower hybrids and the later sown OP varieties. The fast and mid-fast phenology varieties increased or maintained their yield with higher rates of N applied as biomass continued to increase from start of flowering to maturity. The slow developing varieties did not increase their biomass through this period. The results suggest that there is less risk in applying higher rates of N to fast and mid-fast varieties sown in the correct window with a large upside in a good season and risks mitigated in a poor season.

Useful resources

http://grdc.com.au/Resources/Factsheets/2015/09/Blackleg-Management-Guide-Fact-Sheet

References

Brill R, Taylor C, et al 2017, Getting The Best Out Of Canola With In-Crop Agronomy, 2018 GRDC Reasearch Updates Paper, https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/grdc-update-papers/tab-content/grdc-update-papers/2018/02/getting-the-best-out-of-canola-with-in-crop-agronomy

O’Brien B & Street M 2017, High Nitrogen Fertiliser Strategies On Canola, 2017 GRDC Research Updates Paper, https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/grdc-update-papers/tab-content/grdc-update-papers/2017/02/high-nitrogen-fertiliser-strategies-on-canola

Acknowledgements

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by the significant contributions of growers through both trial cooperation and the support of the GRDC — the author would like to thank them for their continued support.

The projects supporting this research are co-investments from GRDC, NSW DPI, CSIRO and SARDI. Thanks to the Longerenong College for the collaboration for the 2016 to 2018 trials. Thanks also to the BCG team for assistance throughout.

Contact details

Cameron Taylor

73 Cumming Ave Birchip 3483

0427 11 65 82

Cameron@bcg.org.au

@cjtaylor_bcg

GRDC Project Code: CSP00187,

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK