Working towards resilient adviser-grower client relationships in the grains industry

Author: Kate Burke (Think Agri Pty Ltd) | Date: 26 Feb 2019

Take home messages

- Be clear in your role.

- Be thorough in your advising and avoid giving instant answers when the situation is complex.

- Be mindful of taking on another person’s stress.

- Accept that not all growers will make the decision you want them to.

- Set boundaries to allow recovery time.

Background and context

Advisers are an integral part of the farm team. So much so that they can become quasi management. This works well for some, but the model can be tested in years when management decisions are complex and there is no obvious answer for a scenario.

2018 was one of those years, and in fact, most years have periods of complex decision making. In a lot of regions in Victoria, the 2018 issue which required complex decision making was handling droughted and/or frosted crops and reviewing the hay option to capitalise on the opportunity presented by the east coast fodder shortage, a situation similar to the period between 2006 to 2008.

In other years, it has been nitrogen (N) decision making (2011, 2016 come to mind) or disease management in unfamiliar crops like the recent Botrytis grey mould outbreak in Mallee lentils or further back in 2000 in the Wimmera.

Advisers were leant on heavily by their clients in 2018 to assess the likely cereal and grain yield outcomes and to estimate the potential for making hay. A straightforward process you might say, however, nothing could be further from the truth.

Except in specialist hay districts, such as Elmore in northern Victoria and parts of the Mid North in SA, growers first and foremost tell me that they like to grow grain. For many, the prospect of surrendering a crop to hay feels like failure even if the financial outcome can be as good as, or better than, the budgeted grain outcome.

Many growers do not own hay making machinery or have experience in hay production. Even adept hay makers find it difficult to cut extra hectares of hay if they already have a large program, as they are fully aware of the logistical nightmare posed by a large hay program and the risk of weather damage during curing time.

Add to that is the uncertainty of the market — if large areas are cut, will the price plunge? Will hay buyers honour verbal agreements and pay up? The bitter taste of bad debtors for hay still lingers even a decade after the millennial drought.

Inevitably, in difficult years the stress is transferred from grower to adviser and on the flip-side, in favourable years, advisers feel the joy of delivering good advice that leads to excellent financial outcomes for the grower.

This paper attempts to answer the following question:

How best do advisers help their clients work towards or maintain a high performing business and at the same time foster a resilient client adviser relationship while maintaining their own wellbeing and professional sense of satisfaction?

What does a resilient client adviser relationship look like?

My view of a resilient working relationship is an arrangement that serves both the personal and business wellbeing of both parties to enable an enduring and sustainable relationship.

A useful definition of resilience offered by McEwen (2016) at an individual levelis:

‘An individual’s capacity to manage the everyday stress of work and remain healthy, rebound and learn from unexpected setbacks and prepare for future challenges proactively’.

This applies to both advisers and growers. A key component of striving for resilience is proactively preparing for challenges.

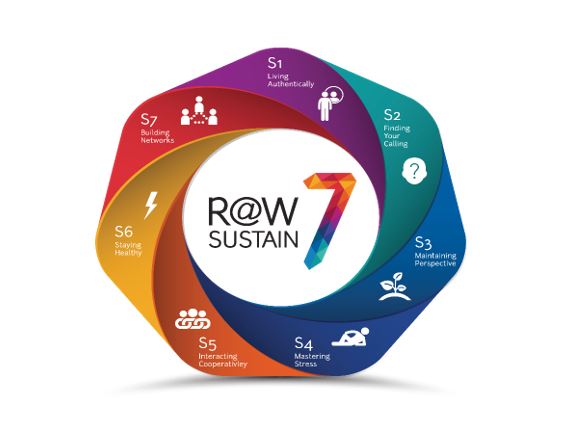

McEwen’s research-based model for building a good overall level of resilience is to invest in seven components described in Figure 1 and Table 1. Developing such capabilities across the whole seven components allows wellbeing and productivity to co-exist over a long period of time.

What does this mean for advisers?

The following practical strategies are offered to proactively manage the client relationship in order to build your own resilience and that of the clients and farm businesses you are working with. These guidelines were developed from several years of experience, both as an adviser for 12 years in Western Victoria and as a client for three years while employed as commercial manager of 10 farms across 80,000ha in four states. Previous roles in research and education have also contributed to the perspective shared in this paper.

1. Be clear in your role

Resilient client-adviser relationships are more likely to occur when both the adviser and client clearly understand the adviser’s role in assisting the farm business. This does not happen by accident and requires clear communication from both parties. In the case of the adviser, it may involve the adviser’s supervisor or employer, depending on the career stage of the adviser. A regular check-in, at least annually, with clients about roles and expectations, is one way of avoiding misunderstandings. Farm businesses have a higher chance of sustained success when the farm management personnel are in control of the decision making and the adviser supports that decision making process by providing informed and evidence based information considering the individual farm situation.This is illustrated in the findings of a recent GRDC project RDP00013 (2016) where high performing farm businesses exhibited the trait of owning the responsibility of decision making within the farm business. As part of the decision-making process, high performing growers had internal ‘rules of thumb’ that they considered in conjunction with professional advice and recommendations. ‘Rules of thumb’ used to guide decision making, either consciously or subconsciously, are generally based on intuition, previous experience and pre-existing knowledge (Long 2013).In the hay versus grain scenario, an adviser will have the highest level of impact and add the most value by:

Ideally the grower can then make and own the final decision.Despite sometimes being pressured to do so, it is not the adviser’s responsibility to make the final decision when it is a line-ball scenario. That responsibility sits with the grower, as the grower must be comfortable in accepting the risks and uncertainty associated with that decision. This is thoroughly described in the GRDC funded publication ‘Farm Decision Making’ authored by Nicholson et al. (2015).

2. Be thorough in your role as an adviser and avoid giving instant answers when the situation is complex

The stakes are large when making major in-field recommendations to support grower decisions, especially complex or complicated ones. The task for the adviser is to support often powerful and season defining decision making worth six figures or more to the bottom line. Suggested approaches include combining:

- Visual observation.

- Objective assessment.

- Data and scenario analysis.

- Working through the issues in partnership with the client.

Document the discussion and calculations used to guide the grower’s decision. This can be a great learning experience for both client and adviser. Should the post-decision outcome not be as expected, the thorough process and documentation can be referred back to.

In uncertain and stressful times, it is human nature to look to blame. Sticking to a process that includes good practice and documentation protects the adviser from unwarranted blame.

Many growers, especially those with many years of experience are intuitive and are more comfortable with gut-feel decision making, especially when the issue is time sensitive, but in some cases, relying on gut-feel alone can be very risky.

Advisers can feel pressured to provide an instant answer, but the risks of providing an uninformed answer can be very high. Process and data driven decision making is the most responsible and professional approach. This process which requires paddock observation, objective measurement, calculations, discussion then recommendation, is sometimes perceived by the grower to take too long.

Despite this conundrum, data driven decision making, if generated in a timely manner, can complement intuition and gut-feel. The combination of the two can be very powerful and reduces the risk of gut-feel being derailed by stress. Nicholson et al. (2015) provide extremely useful practical advice on advising and decision making.

Figure 1. The seven components of resilience (McEwen 2016).

Table 1. Practical strategies for working towards resilience at work (McEwan 2016).

S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | S6 | S7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Living authentically | Finding your calling | Maintain perspective | Managing stress | Interacting co-operatively | Staying healthy | Building networks |

| ·De-stressing and debriefing techniques ·Time management and prioritisation ·Workload negotiation ·Work life blend ·Being mindful and present |

|

3. Be mindful of taking on another person’s stress

A useful skill when providing advice in pressure situations is to be able to listen to other’s angst, without absorbing too much of that angst for too long. This can be hard for empathic and compassionate people and requires substantial self-management.In the heat of the season, it is busy and demanding and sometimes there are no simple answers. It is a very natural response to ruminate over the advice you have provided and worry excessively. While empathy comes hand in hand with a good client adviser relationship, the client is best served when your decision making is based on logic rather than emotion.Practical tips to manage your personal stress include staying healthy by getting adequate sleep, eating well, exercising and scheduling fun and relaxation.Failing to look after yourself will impact on your personal wellbeing and on the quality of service you can provide your clients. The resilience at work scale (McEwen 2016) is one practical model that provides guidance for a holistic approach to staying well and achieving at work. (Table 1).

4. Accept that not all growers will make the decision you want them to

When uncertainty and stress are rife, our brain goes into flight or fight mode and tends toward emotionally driven decision making rather than rational decision making (Bradberry 2015).

The grower’s decision may also be influenced by business or personal factors that you are not privy to. Despite your diligent, well informed and rational advice, there will inevitably be growers whose decisions may be contrary to your judgement and advice.

In that case, document your advice in writing, have the conversation, then leave it there. At the end of the day, it is their farm, not yours and you cannot control their decision making or their actions.

Nicholson et al. (2015) described some key factors that can increase the odds of client buy in:

- Involving the grower in the recommendation process so they understand and take ownership of your recommendations.

- Listen and consider their values, goals and motivations so that the advice is tailored to their business.

- Consider the emotional and financial risks involved.

5. Set boundaries to allow recovery time

‘Stress is not the problem, the problem is lack of recovery’ is a phrase used by Mark McKeon, a high-performance coach and regular speaker at GRDC events (McKeon 2011, McKeon 2018).

Living and working in small communities means you may be socialising with your clients. This is tricky as there is little escape when everyone wants to ‘talk shop’ at the pub or at footy. To serve your clients well, you need to be able to relax and recover by doing enjoyable things on weekends without the pressure of being in work mode 24-7. Most clients are generally respectful when boundaries around private time are set.

Simple strategies like turning your phone off after dinner and on the weekends will give you time and space to reset for another solid week of paddock checking and client problem solving.

Conclusion

Advising and problem solving for growers is a satsifying professional experience and extremely important, but it can be difficult in some seasons. Tips to minimise the impact of difficult advisory times include:

- Be clear in your role.

- Be thorough in your advising and avoid giving instant answers when the situation is complex.

- Be mindful of taking on another person’s stress.

- Accept that not all growers will make the decision you want them to.

- Set boundaries to allow recovery time.

References

Bradberry T 2015. Eleven ways successful people overcome uncertainty. https://www.forbes.com/sites/travisbradberry/2015/12/21/11-ways-successful-people-overcome-uncertainty/#3bac66092475

GRDC RDP00013 2016 Project Report for the integration of technical data and profit drivers for more informed decisions, authored by Rural Directions Pty Ltd, Macquarie Franklin, Meridian Agriculture, Agripath, and Corporate Agriculture Australia. GRDC Canberra ACT.

Long W 2013. Understanding Farmer Decision Making And Adoption Behaviour. https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/grdc-update-papers/tab-content/grdc-update-papers/2013/02/grdc-updatepaper-long2013-decisionmakingandadoption

McEwan K 2016. Building your resilience. How to thrive in a challenging job. Mindset Publications www.workingwithresilience.com.au

McKeon M 2011. Get into the Go Zone. Making the most of me. Inspiring Publishers Canberra ACT.

McKeon, M 2018. Sustainable peak performance for advisers. https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/grdc-update-papers/tab-content/grdc-update-papers/2018/02/sustainable-peak-performance-for-advisers

Nicholson C, Long J, England D, Long B, Creelman Z, Mudge B, Cornish D 2015. Farm Decision Making: the interaction of personality farm business and risk to make more informed decisions. GRDC Project SFS000028 GRDC Canberra ACT.

Acknowledgements

Kate Wilson, Agrivision and GRDC Southern Panel Member who provided valuable suggestions for this paper.

Contact details

Kate Burke

Echuca

0418 188565

kateburke@thinkagri.com.au

@think_agri

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK