Understanding the fit of winter wheats for WA environments

Author: B Shackley, J Curry and D Nicol, DPIRD (Katanning, Esperance and Merredin) | Date: 08 Mar 2022

Key messages

- Illabo was the most competitive winter wheat variety when sown mid-April in the longer cooler environments of WA.

- Current winter wheats were typically still flowering too late, even when sown in early April, suggesting the need for earlier flowering winter type varieties for the medium to lower rainfall areas.

- Agronomic recommendations are listed to maximise the performance of winter wheat in WA.

Aim

To assess commercial and potential winter and spring wheat varieties for their suitability (yield, phenology and dry matter production) to early sowing opportunities in WA.

Introduction

Grower interest and demand for winter wheats has increased in WA due to recent early sowing opportunities and the logistics of sowing larger cropping programs on time coupled with research highlighting the benefits of winter varieties (Hunt et al. 2019).

Wheat varieties can be broadly classified into two types: winter or spring depending on their flowering response to vernalisation (cold requirement) and their adaption to different sowing dates. Winter wheats can be sown early (i.e., from late March to late April) and require an accumulation of cold temperatures (vernalisation), before they will progress from the vegetative to reproductive development stage. This results in a relatively stable flowering time when sowing advances earlier and into warmer autumn conditions. In contrast, spring wheats generally require little to no vernalisation to initiate flowering and development is sped up in response to warmer growing conditions. However, with multiple combinations of vernalisation and photoperiod genes, there is a wide variation in flowering response among both winter and spring types in response to sowing time across environments.

Historically, there has been very little breeding effort into developing winter wheats to suit southern Australia apart from the NSW Agriculture breeding program based in Wagga. Recently breeders have responded by releasing several winter varieties, with more in the pipeline. Most of the winter wheats are from eastern states genetic backgrounds that can fail to perform strongly in WA, particularly in warmer growing environments. It is therefore critical to define the management and environmental conditions under which the performance of the new winter wheat varieties will be maximised in WA.

Method

Early sowing opportunities

A series of time-of-sowing trials were located at Mullewa, Merredin (Merredin Dryland Institute), Dale, Katanning (Great Southern Agriculture Research Institute) and Grass Patch. These trials examined 24 wheat varieties sown at four to five sowing dates. The varieties ranged from winter types to short maturing commercial varieties and unreleased lines. The sowing dates were similar at all five sites and will be collectively referred to as early-April (ranging from 9-14 April across sites), late April (22-28 April), early May (8-13 May), late May (18-24 May) and early-June (3-14 June).

A range of winter, slow and mid-slow spring wheat varieties were also sown 25 March, 21 April and 21 May at Gibson.

In 2021, the Mullewa site received irrigation to ensure germination with 25mm applied before the early April sowing while late April and May sowings received 5-8mm. At Dale, the late April sowing received 12.5mm after sowing. All other sites or sowing times were rainfed.

Trials were sown as six banks of small plots (10 to 12m long x 1.54m wide) with three replicates per time of sowing. The time-of-sowing trials were fully randomised, including the sowing times, while the Gibson trials were sown as “blocks” hence no comparisons can be made between the sowing times. All trials were sown into canola stubble (except Merredin, which followed wheat) with fertiliser (treated with Uniform®) banded below the seed (treated with Emerge®). Plots were seeded to target an establishment of 150 plants/m2. Further nitrogen was applied at 4-8 weeks after sowing as Urea-Ammonium Nitrate or Urea, and fungicides were applied as required to control any disease compendium.

Heading and flowering dates were recorded once (Dale), twice (Katanning and Grass Patch) or three times per week (Merredin), as Zadok scores. Plots from each time of sowing were harvested as soon as grain moisture was below 11% for most varieties, hence sowing times and later maturing winter wheats were often harvested at different times. Small plot harvesters were used at each site, with grain yields recorded and grain samples taken and cleaned for quality testing.

Dry matter accumulation

The late April and late May sowing time “blocks” at Gibson and an early April “block” at Katanning were also sown with paired plots to enable destructive sampling of the plots.

Quadrant samples (0.53m²) were taken 6-7 weeks after sowing and then every 4 weeks until maturity at Gibson. At Katanning samples were taken every 2 and then 4 weeks until 15 weeks after sowing (July 23), thereafter a late weed germination became an issue.

Results

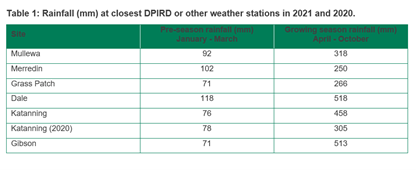

In 2021, pre-season (January to March) rainfall deciles ranged from 5 to 9 at Gibson and Mullewa respectively while growing season rainfall (April to October) ranged from 6 at Grass Patch to 9 at most other sites (Table 1). Frost damaged many areas in the eastern wheatbelt, including the trial at Merredin (data not reported in this paper). Katanning had some minor frost damage which was associated with the mid-April sowing and the quicker maturing varieties (e.g., varieties with similar or quicker maturity than Scepter). A similar level of frost damage occurred at Katanning in 2020. Weeds became an issue at the Katanning site, reducing the yields for all varieties sown mid-April compared to late April, hence the 2020 data is shown in Figure 2.

Early sowing opportunities

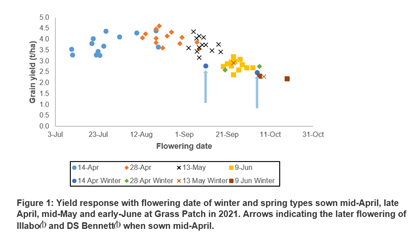

Flowering date is critical for wheat yield, with flowering required to occur within an optimal period to minimise the effects of frost, heat and drought on yield. Figure 1 shows the trend of grain yield with flowering date, highlighting the late flowering date of the winter types, namely DS Bennett and Illabo, and the associated lower grain yields. Winter types fit within the quadratic trend achieved by the spring wheats, where grain yields increased from early April to early May sowings before decreasing at later flowering dates (particularly evident in early-June sown treatments), a response also found at other sites and years (Shackley et al 2019).

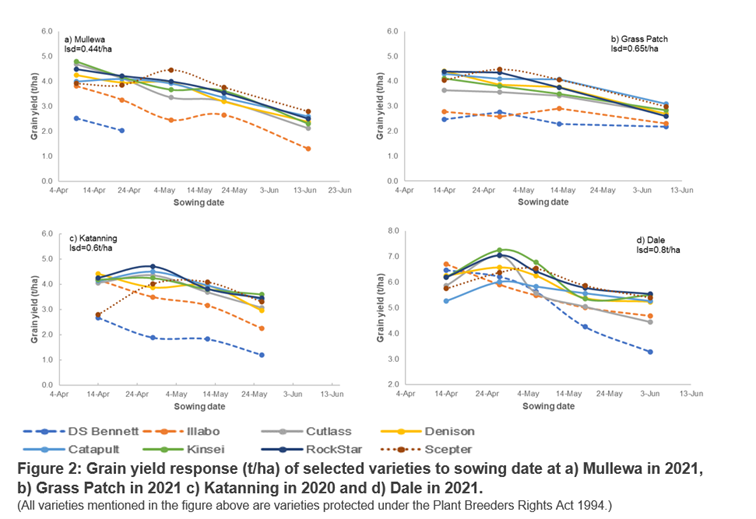

Figure 2 shows the grain yield response of winter (DS Bennett and Illabo), mid-slow (Cutlass, Denison, Catapult, Kinsei and Rockstar) and quick-mid (Scepter) varieties to sowing date at four environments in 2021. Similar yield responses were found in previous years (Shackley et al 2021. 2022 WA Crop Sowing Guide, page 24). Early April sowing is not necessarily associated with increased yields as shown at Katanning and Dale for spring wheats, or the yields can be similar to later sowing dates as seen at Grass Patch. Early April sowing is also not associated with winter types achieving the highest yields in warmer (Mullewa) or lower rainfall (Grass Patch) environments, with mid-slow spring types typically achieving the highest yields when sown in April.

The slower developing winter wheats, such as DS Bennett and Illabo are more suited to the cooler and medium to high rainfall environments in WA which have a longer growing season and/or an increased risk of frost i.e., Katanning and Dale. The vernalisation requirements of the winter types make them less suited to the warmer environments of Mullewa, Merredin (not shown) and Grass Patch.

The trend for the winter wheat yield at Katanning and Dale (Figure 2c and d) suggests they need to be sown earlier than mid-April to achieve higher yields. Unfortunately, this data is limited and often in the context of a single sowing.

A late March sowing opportunity at Gibson found RockStar to yield the highest, followed by Denison, Illabo and Longsword. Significantly lower yields were achieved by DS Bennett and RGT Accroc due to high levels of take-all (results not shown). This indicates that in environments where frost, heat and drought are less relevant, flowering date is not as critical as potential yield (set by yield components) and other factors such as disease resistance. Grain quality issues such as black point and lower falling numbers may also lead to downgrading of early sown spring wheats (Shackley et al 2019).

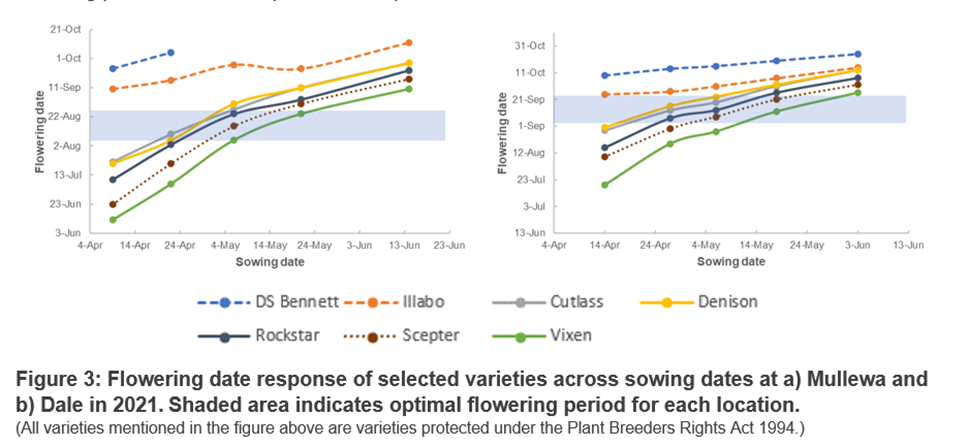

Flowering gap between winter and spring types

Winter types have a relatively stable flowering date across a broad range of sowing dates (Figure 3). In comparison, the spring wheats have a less stable date of flowering, which becomes more evident as the sowing date is pushed earlier. Consequently, winter types tend to flower too late for many environments in WA and there is a large gap of suitable varieties which can flower in the optimum flowering period when sown prior to late April.

Early dry matter comparison (potential grazing value)

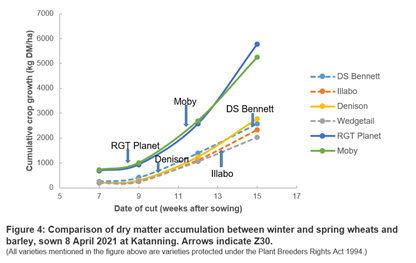

Winter crops can be ‘dual purpose’ as they can be successfully used for grazing and grain. The benefit of using a winter type for grazing is the longer time they remain vegetative, and the trigger is often more predictable with the winter type than the spring type. At Katanning, DS Bennett and Illabo reached stem elongation at similar times when sown mid-April in either 2020 or 2021, compared to spring wheats such as Denison where there was a difference of 11 days between years (data not shown). When sown in early April, there was about two weeks difference in time to stem elongation between DS Bennett and Illabo and over two weeks between Illabo and Denison (Figure 4).

Dry matter accumulation of winter and spring wheats and barley was examined at Katanning (Figure 4) and of wheat only at Gibson (not shown). Barley provided more rapid early growth than the wheat varieties as previously shown by Grain & Graze (Nicholson et al 2016). There was little difference between the varieties within barley or wheat types on dry matter production at Katanning. Grain & Graze also observed a minor influence of varieties within crop type when compared at the same sowing time, sowing rate and climatic conditions. Length of required grazing period and crop recovery/ final grain yield (not measured) will influence the choice of crop type and variety used as a dual-purpose crop.

Conclusion

This research again highlights the need for a wheat variety better suited to early April or earlier sowing opportunities in WA. While winter types have an extended growing period when sown in early April, maximum yields are almost always achieved by mid-slow spring varieties sown in late April to early May. Winter wheats generally flower too late for maximising yield potential even when sown in early/mid-April. The role of winter and slow or mid-slow maturing wheat varieties are currently undervalued in the WA cropping system.

To maximise the performance of winter wheat in WA, the recommendations are:

- Sow early sow slow – Match variety × sowing time to reduce risk of frost or heat/drought stress. Illabo is currently the most widely adapted winter wheat in WA, but note that winter wheat varieties are also susceptible to frost, so pick your site.

- Don’t sow too early – March sowing data is limited for WA; however, establishment can be difficult with high temperatures and drying seed bed. Unless grazed, excessive biomass can lead to haying-off, while insufficient biomass due to stress or bolting and lodging can also occur. There is an increase in disease pressure, viral, root and leaf. Research from South Australia and Victoria show a decline in yields once sowing moves earlier than April 1 (Ten tips for early sown wheats, GRDC 2020).

- Select your paddocks carefully – early sown crops perform best in paddocks with a very low weed burden. If in doubt use a robust pre-emergent herbicide package to ensure a longer control period. Watch for any phenology differences between varieties and the impact of this on spray windows.

- Don’t sow too deep or dry sow – coleoptile length is often very short in winter wheats and dry sowing is a risky option if the break occurs later than expected.

- Don’t reduce seeding rates too much – yields of early sown crops are unaffected by plant density but very low plant densities compete poorly with weeds. If grazing is planned higher seeding rates ensure a better establishment and higher amounts of early dry matter (Zaicou-Kunesch et al 2019). Higher densities were not lower yielding.

- Nitrogen can be delayed – to help reduce excessive early growth and haying-off however, if grazing, deferring nitrogen will reduce the amount of dry matter available. Winter wheat for grain only can be top-dressed at a similar time to main season spring wheats.

- Manage pests and diseases – winter wheats are exposed to potential invertebrate pests and diseases for a longer period, so active or preventative control measures need to be in place.

- Grain & Graze – follow recommendations to cease grazing before stem elongation (or Z30) to reduce the risk of yield loss. Grazing can lead to delay in crop maturity (Grain & Graze, 2016).

References

Hunt, J., Lilley, J., Trevaski, B., Flohr, B., Peake, A., Fletcher, A., Zwart, A., Gobbett, D., and Kirkegaard, J. (2019) Early sowing systems can boost Australian wheat yields despite recent climate change. Nature Climate Change, 9, 244-247.

Grain & Graze. Nicholson, C., Frischke, A., and Barrett-Lennard, P. (2016). Grazing cropped Land: A summary of the latest information on grazing winter crops from the Grain & Graze Program. GRDC.

GRDC (2020) Ten tips for early sown wheats. Available at https://grdc.com.au/ten-tips-for-early-sown-wheat

Shackley, B., Zaicou-Kunesch, C., Curry, J., and Nicol, D. (2019). Which wheats for when? GRDC WA Grains Research Update, Perth, WA, 25-26 Feb 2019.

Zaicou-Kunesch, C., Curry, J., Shackley, B., and Trainor, G. (2019). Agronomy of early sown wheat in WA. GRDC WA Grains Research Update, Perth, WA, 25-26 Feb 2019.

Acknowledgments

The research undertaken as part of this project is made possible by DPIRD funding. Sincere thanks to the Glenn Thomas for the provision of land at Mullewa, to the Geraldton, Merredin, Katanning and Esperance RSUs, Living Farm and Ghazwan Al Yaseri for the management of trials and for the technical support of Melanie Kupsch, Nihal Hewage, Nathan Height, Rod Bowey and Helen Cooper.

Paper reviewed by: Brenton Leske

PBR Symbol Varieties displaying this symbol beside them are protected under the Plant Breeders Rights Act 1994.

® Registered trademark

Contact details

Brenda Shackley

DPIRD

10 Dore St, Katanning

Ph: 9821 3243

Email: brenda.shackley@dpird.wa.gov.au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK