Spray application manual

15 March 2025

Module 2: Product requirements

2.3: Uptake and translocation of herbicides

Published 24 January 2025 | Last updated 20 January 2025

Formation of herbicide deposit on leaf

Once a spray droplet lands on a leaf surface, most surfactant systems within most formulations will tend to cause the droplet to spread. The amount the droplet will spread depends on the surface tension of the spray solution and the characteristics of the leaf surface.

Droplets with a low surface tension will spread more easily than droplets with a higher surface tension. The type and amount of adjuvant, either in the formulation or tank mixed, can significantly impact on the surface tension of the spray droplet.

After spreading, the droplets may begin to dry out, due to the evaporation of water from the droplet. Small water-based droplets and those that spread easily will tend to dry out faster than large droplets, as the surface area of these well-spread droplets is significantly greater than the surface area of a similar volume droplet that has not spread.

In order for herbicides based on water-soluble formulations to enter the leaf they must remain dissolved in the water droplet. Once the water has evaporated from the droplet a crystalline deposit remains and movement of the herbicide into the leaf stops, unless it is capable of being re-wet by high humidity, dew or light rain.

The uptake of oil-based (lipophilic) herbicide formulations (for example, emulsifiable concentrates or esters) is less influenced by the speed of evaporation of water from the spray droplet because they are able to move into the leaf more rapidly via a different pathway.

Note

Leaf surfaces can be covered by many structures and different types of wax that can impact on droplet contact with the leaf surface and the uptake of products by the plant.

Very large droplets (Very Coarse and larger) are good for reducing off-target spray drift and are slower to evaporate, so are often chosen for summer applications. The downside of these large droplets is that it can be hard to get these droplets to stick, especially on difficult surfaces like small grass weeds.

To attempt to achieve better retention, it is common to see users adding additional 'spreading' non-ionic surfactant or a crop-oil-concentrate. These surfactants may assist droplet retention, by reducing the surface tension of the droplet. However, due to the same effect of reduced surface tension, they also will typically reduce the average droplet size (increased drift risk) and the droplets may evaporate faster and reduce leaf entry under high Delta T conditions for water soluble herbicides, especially glyphosate or glufosinate. In some situations, it may be counterproductive to select a coarser nozzle for drift reduction reasons, but then need to add a 'spreading' surfactant in order to assist leaf retention.

For products like glyphosate which has specific surfactant requirements, it is typically best for summer spraying to use a formulation containing a quality in-built surfactant system to avoid the need for in-tank mixtures of ‘spreading’ non-ionic surfactants or crop-oil-concentrates.

Tank-mixing glyphosate with coverage sensitive partner herbicides such as Group 1 and Group 14 herbicides can be particularly challenging. These partners work best when applied at higher water rates and with the addition of a crop-oil-concentrate adjuvant (e.g. Uptake®, Hasten®). Glyphosate works best at lower water rates and with a non-spreading, but penetrating, surfactant system. Tank mixing will be a compromise at best, especially for summer applications.

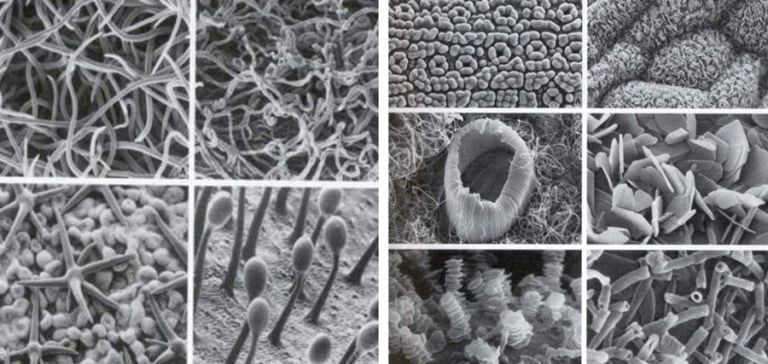

Electron micrographs

Movement of herbicides to plant site of action

Foliar herbicides

Foliar-applied herbicides have to move through the leaf or stem cuticle and epidermis into the target cells within the plant.

For most applications, very little herbicide moves into a plant via the stomata (pores in plant leaves used for gas exchange).

Soil-applied herbicides move from the soil solution into plant roots and shoots. This movement is primarily by diffusion.

Definition of ‘diffusion’

The movement of atoms or molecules from an area of higher concentration (herbicide droplet) to an area of lower concentration (water-filled inside of the leaf).

The leaf cuticle is designed to regulate water loss from the leaf. The cuticle is made up of a range of waxes and fatty acids and/or small hairs (trichomes) depending on the species and the environmental conditions the plant has experienced.

The cuticle is multi-layered. Externally it primarily consists of a layer of epicuticular waxes, while the underlying layer is a mix of waxes and cutin (a water-filled spongy material).

The hydration of the cuticle changes with environmental conditions, so as to regulate water loss through the leaf surface. Under high Delta T conditions (hot temperatures, low humidity) the cuticle dehydrates which in turn reduces plant transpiration through the leaf surface (at the same time the plant will close stomata so as to further reduce transpiration losses).

This is important for uptake of water-based (hydrophilic) herbicides, which need to penetrate the waxy cuticle. As the cuticle dehydrates under hot, low humidity conditions this further slows the speed of leaf uptake of water-soluble herbicides. At the same time, these hot/dry environmental conditions are rapidly drying the spray droplet. This results in less hours available for uptake before the hydrophilic (water loving) herbicide has become crystalline and further uptake ceases.

As a result, the leaf uptake of herbicides such as glyphosate and glufosinate are severely reduced under high Delta T environmental conditions - with the outcome being either poorer performance and/or the need to use higher application rates in summer. As typically only a small percentage of the applied dose will penetrate the leaf before crystallisation occurs on the leaf surface.

Surface tension of the droplet and the characteristics of leaf surface both influence droplet spread (bottom picture). Adjuvants that lower surface tension (right hand side picture) can improve droplet spread to allow for greater uptake of the product by the plant, although this will spread the droplet and therefore accelerate water evaporation from the droplet.

Waxy and hairy leaf surfaces

Some herbicides are formulated as ‘pro-herbicides’ to improve their movement through the cuticle. Once inside the plant they are converted to the active herbicide. A good example of this is Group 1 'fop' herbicides that are formulated as esters to assist leaf uptake. Once inside the leaf they are rapidly converted to the parent acid, which is the active form.

2,4-D is another useful example. 2,4-D acid is the active form inside the plant, but is poorly taken up by the leaf if applied as the acid. 2,4-D products are generally formulated as an ester (lipophilic form) or as an amine (hydrophilic form). Both increase leaf uptake compared to the parent acid, however the lipophilic ester will penetrate the waxy cuticle much faster than the hydrophilic amine form.

These differences in speed of cuticle uptake can generally be seen when looking at rainfast periods on labels. Typically products that are lipophilic (including esters) often have rainfast periods of around 1 hour. While salt/amine formulations typically have rainfast periods commonly in the range of 4-6 hours, indicating the additional time required for adequate leaf entry.

Water-soluble (hydrophilic) formulations move (slowly) through cuticular pores along what is called the ‘aqueous route’. Low humidity and moisture stress break the continuity of this pathway, reducing the ability of these herbicides to enter the plant. Oil-based (lipophilic) formulations move directly through the cuticle waxes and are less affected by moisture and environmental stress.

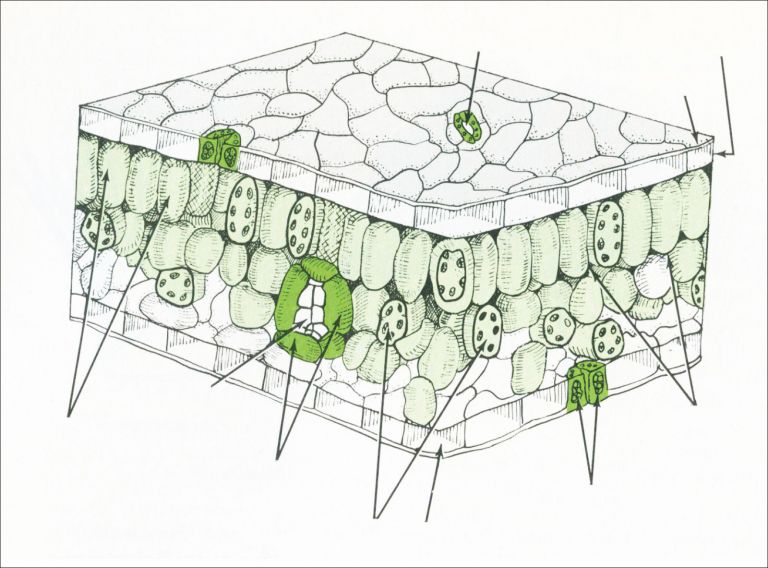

Cross-section of a leaf

Once through the cuticle and epidermis the herbicide enters the water-filled section surrounding the cells (apoplast). Movement through the water-based apoplast is much easier for hydrophilic (water loving) herbicides. Lipophilic (wax/lipid loving) herbicides find movement through the aqueous apoplast difficult, which reduces their ability to translocate.

Therefore, strongly lipophilic herbicides will be quickest to move through the cuticle but then movement slows down (or stops) through the apoplast. While very hydrophilic herbicides may struggle to penetrate the cuticle, but then movement increases once reaching the apoplast.

Often the best properties for both herbicide leaf uptake and movement within the leaf are from herbicides which are somewhat intermediate between either extreme. A good example of this are many Group 2 herbicides.

Soil-applied herbicides

Soil-applied herbicides are either taken up by plants through their roots or the emerging shoots of seedlings. The water solubility of soil-applied herbicides determines how they need to be applied. For example, trifluralin (Group 3) is practically insoluble in water and does not move in the soil so must be placed where it will come into contact with germinating weed seeds.

Other herbicides, such as metolachlor, are quite water soluble so can move down the soil profile to weed seeds with moisture from rain or irrigation. Water-soluble herbicides therefore require less incorporation.

Water solubility is an important consideration, particularly where heavy stubble loads exist. Residual herbicides that bind strongly to organic matter and have low water solubility require droplets to be directly deposited onto the soil surface, which may require the stubble to be removed / incorporated before herbicide application. This can have implications for the sprayer set-up, nozzle choice, spraying speed and incorporation technique and also the position of weed seeds in the soil profile if cultivation is used for stubble removal.

Herbicide activity inside the plant

Plant cells are surrounded by a membrane through which oil-soluble herbicides pass quickly into the cell cytoplasm by simple diffusion, while water-soluble herbicides move more slowly, often requiring additional cell membrane transfer pathways in addition to diffusion (e.g. transporters or ion-trapping of weak acid herbicides).

Distribution of the herbicide within the plant

Once inside the plant, translocated herbicides are distributed via either the xylem or the phloem. These are distribution systems for nutrients within the plant.

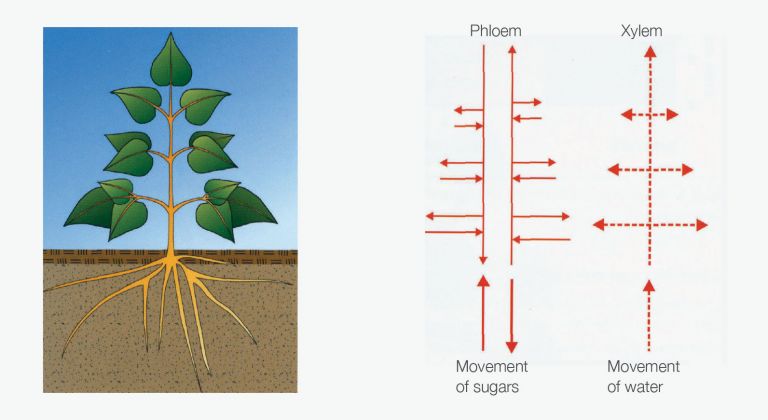

Diagram of plant with xylem and phloem showing direction of movement

The xylem is a plumbing system for the movement of water and minerals from the roots to the shoots and is a one-way system. Flow in the xylem is determined by environmental conditions such as available soil water, humidity, temperature and light intensity.

Herbicides must be water soluble to move in the xylem.

Some soil-applied herbicides move from the roots to the leaves and shoots through the xylem and out to the edges of the leaves.

The phloem is a system of living cells that distributes sugars and amino acids throughout the plant and is a two-directional system. Herbicides that move within the phloem need to have reasonable solubility (intermediate or hydrophilic) and typically be a weak acid so as to be able to cross cell membranes within the phloem pathway.

For a foliar herbicide to be able to translocate downwards from the site of leaf entry it must have these properties to facilitate phloem movement.