Australia’s grains industry in 2030 - a look into the future

Author: Ross Kingwell (Australian Export Grain Innovation Centre (AEGIC)). | Date: 11 Feb 2020

Take home message

- South Australia’s grains industry is well poised to benefit from strategic change in Australia’s grains industry.

Background

Dorothea Mackellar’s famous poem, My Country, sums up Australia as a land ‘of droughts and flooding rains’. Her assessment, written over a century ago, remains apt. Australia’s environmental extremes of drought, flood and bushfire continue to seriously disrupt Australian agriculture; affecting livestock and grain production, and lessening exports of agricultural commodities. Also largely unchanged is the familial basis of farm production in Australia. Yes, farms are larger; yes, there is greater mechanisation; yes, there are fewer farm families but, most of the grain, sheep and wool production still comes from farm families who pass their farm business wealth, knowledge and skill in farming down through their generations.

However, many other things are changing to affect greatly or gradually farm production, especially grain production, in Australia. The list of factors includes:

(i) Technological change. Long gone from Dorothea Mackellar’s era is the vital role of horses in crop production. Now, powerful machinery with in-built precision and intelligence aid the sowing, spraying and harvesting of crops. Bulk-handling underpins most aspects of crop production. Computer and mobile phones facilitate communication, commercial transactions, information receival, record-keeping and various types of analysis.

(ii) New crops and changing crop mixes. The wheat-sheep belt, the mainstay of Australian agriculture, has switched its land use to favour more crops, with greater crop diversification. Canola, chickpeas, lentils and lupins, once virtually unknown crops, have emerged to be important components of cropping systems in different regions. The swing into greater reliance on crop revenues is evidenced by Australia’s sheep population shrinking to current levels as small as it was in 1905, 115 years ago. Yet, by contrast, in 1905 in Australia, 1.5mmt of wheat was produced from 2.5mha compared to 15.9mmt being grown on 10.1mha in 2019.

(iii) Altered soil management. Traditionally paddocks were ploughed repeatedly to form a friable seed bed to combat weeds. However, the advent of conservation agriculture (Kingwell et al. 2019) now sees crops established in single pass operations, with minimal soil disturbance with increased reliance on herbicides and weed seed management at harvest. Soil amelioration is increasingly commonplace (Davies et al., 2017).

(iv) A changing climate. Grain production in Australia is based on rain-fed farming systems. Hence, temporal and spatial changes in rainfall and temperatures crucially affect national crop production. Investigations of long-term weather records reveal a warming trend underpins Australian grain production. Winter crop regions, especially in Western Australia (WA), are also affected by a downward trend in growing season rainfall. Extreme heat during grain filling poses a further problem in some regions where farmers observe occasional ‘heat frosts’ with grain yield and grain quality being adversely affected.

(v) An altered role of government. Traditionally, government played a major role in Australia’s grain industry. Rail systems were owned and operated by State governments. Statutory grain marketing was ubiquitous. Research and advisory services were funded and supplied principally by State governments, with the Commonwealth government playing an important collaborative role in research funding. Provision of new plant varieties was almost solely the province of State government agencies, universities and the CSIRO. Governments were important employers in many rural towns. Yet now, the march of privatisation, the lesser, relative economic contribution of agriculture and the emergence of other claims on the public purse from environment (natural disaster relief, environment, health and social welfare) have altered the role of government in the farm sector. Increasingly grain growers pay fully or a large part for advice, grain marketing, research services and grain transport.

Privatisation has not only affected government services, grain handling and storage that typically was under cooperative ownership and management by grain growers also has passed into private ownership; Cooperative Bulk Handling in WA being a key exception.

(vi) Emergent low-cost overseas competitors. Over the last few decades, a seismic shift in grain export prowess and rankings has occurred. In previous decades North America, Europe and Australia were the main grain exporters. However, first South America (i.e. Brazil and Argentina) and then the Black Sea region (i.e. Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan) greatly have increased their grain production and grain exports. AEGIC have released reports on several of these grain exporters (for example; Kingwell et al. 2016a, 2016b and Kingwell and White 2018). Russia has replaced the USA as the world’s main exporter of wheat. Argentina and Brazil are the main export suppliers of feed grains (soybean and corn).

All these changes, in combination, are affecting the current and future potential of grain production in Australia. Drawing on these changes and other key influences, the next section of this paper outlines a possible future for Australia’s grains industry at 2030. The ramifications for South Australia (SA)’s grains industry are highlighted.

Australia’s grain industry towards 2030

Late last year I released a report (Kingwell 2019) that describes the likely situation and outlook of Australian grain production towards 2030. Similarly, Rabobank examined strategic trends in Australia’s grains industry and came to a similar conclusion that, towards 2030, feed grain demand and supply will increase in prominence in Australia, especially in eastern Australia.

Any interested readers can read the full report, but for now, the report’s following key findings are highlighted.

Key findings

- Australia’s population is projected to increase by between 16 and 19 per cent by 2030. This means between 4.07 and 4.89 million additional people in Australia.

- Little increase in the area sown to winter and summer crops in Australia has occurred since the mid-2000s and further increases are unlikely towards 2030.

- Despite plant breeding, agronomic and technology improvements, the average rate of crop yield improvement has been 0.6 per cent per annum since the late 1980s. There is spatial variation in yield improvement trends and yield volatility has worsened in eastern Australia.

- Climate change and seasonal variation are limiting yield growth in many grain-growing regions.

- The mix of crops grown across Australia is fairly stable with a slight increase in the relative importance of canola over the last decade. In eastern Australia, coarse grains and pulses feature more in the mix of crops.

- The pattern of meat consumption among Australians is changing, with a growing dominance of chicken and pork consumption at the expense of beef and lamb.

- Increasingly, the main meats consumed by Australians are from grain-fed animals.

- By 2030:

(i) Feed grain demand in Australia will increase by between 2.24mmt and 2.48mmt.

(ii) An additional 0.64mmt to 0.77mmt of grain will be required for flour and malt production.

(iii) An additional 5.65mmt of grain will be produced, increasing from current production of 49mmt in 2017/18 to 54.6mmt.

(iv) The surplus of grain available for export is expected to be between 2.4mmt and 2.8mmt.

(v) Almost all the additional grain production in eastern Australia will need to flow to the east coast domestic market to satisfy its growth in feed and food demand based on grains.

(vi) The main sources of additional exportable surpluses of grain will be in WA and SA.

(vii) The grain quality profile of Australia’s main export crop, wheat, is likely to alter, as WA’s and SA’s share of national wheat exports increases.

A key implication of these findings is that towards 2030, Australia’s domestic requirements for grain will become increasingly important, especially in eastern Australia where most of the population increase and greater demand for feed grains, flour, oil for human consumption and malt will occur. By contrast, most of the exportable surpluses of grain will increasingly come from the less populous states of WA and SA.

The task of finding export markets for the additional 2.4mmt to 2.8mmt of export grain available by 2030 may not be overly challenging, given the projected increase in grain imports envisaged for many of Australia’s current grain customers. Nonetheless, it needs to be noted that this task of selling more Australian grain will occur against the backdrop of burgeoning exports from low-cost international competitors previously mentioned.

Assuming crop production in Australia towards 2030 remains seasonally volatile, while the east coast domestic demand for grain increases in relative importance, then farmers and grain users are likely to react by:

(i) Investing in more grain storage; especially while interest rates are low, making the cost of carrying grain affordable.

(ii) Focusing more on domestic market opportunities, especially in eastern Australia.

(iii) Focusing more on feed grain production, especially in eastern Australia and possibly in an adjacent state like SA.

(iv) Opportunistically selling grain from SA and WA to end-users in eastern Australia when low production occurs on the east coast. However, this will adversely affect SA’s and WA’s reputation as reliable exporters to overseas’ consumers.

(v) Looking more closely at grain supply security when investing in export-focussed grain processing/animal protein industries; with access to export parity grain rather than exposure to import parity on the east coast.

Implications for SA grain producers

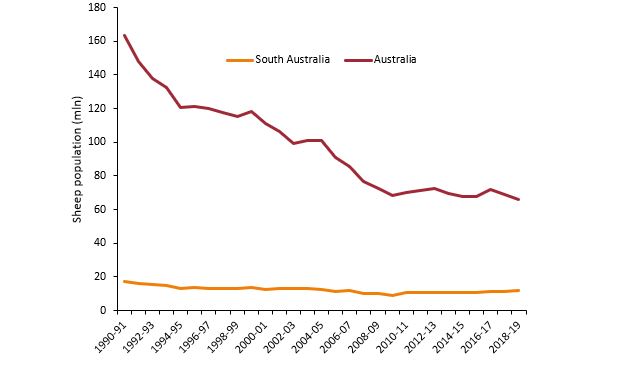

Although the increased demand for feed grains in eastern Australia may encourage more SA grain producers to alter their crop mix towards more feed grain production, it is unlikely that most farmers will additionally allocate more land to cropping rather than sheep production. Despite the sizeable reduction in the national sheep population, SA farmers have maintained their investment in sheep (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sheep population in Australia and SA since 1990.

In order to retain sheep numbers, either pasture areas need to be allocated for sheep production or affordable feed grains need to be always readily available. Given the strong upward movement in sheep meat and wool prices over the last several years, on a gross margin basis, farmers are unlikely to switch land and other resources away from sheep production. Moreover, as the domestic and overseas demand for sheep meat and wool continues to expand, then retention of sheep in farming systems is increasingly likely. In addition, retaining sheep provides a means to add value to feed or downgraded grain produced on a farm. Currently, sheep enterprises form a profitable, risk-diversifying role for many SA farm businesses. As a result, SA crop production growth will be based largely on yield increases rather than crop area increases. Accordingly, crop breeding and crop agronomy will play crucial roles in ensuring gains in crop production in SA.

In coming decades, the traditional flow of grain from SA farms down to ports for overseas export could be a less dominant feature of SA crop production, as east coast demand for grain increases in relative importance; especially in years of low production in eastern Australia. Interstate grain flows from SA are likely to feature more frequently. SA’s small domestic market and SA’s more reliable climate for grain production will facilitate grain flows into NSW and Qld. These grain flows however, will affect the returns from owning infrastructure (trains, port terminals, port storage) required for grain export.

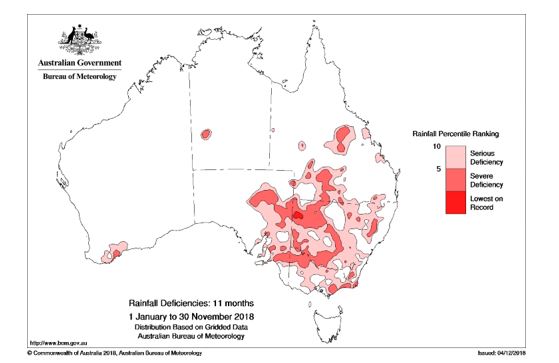

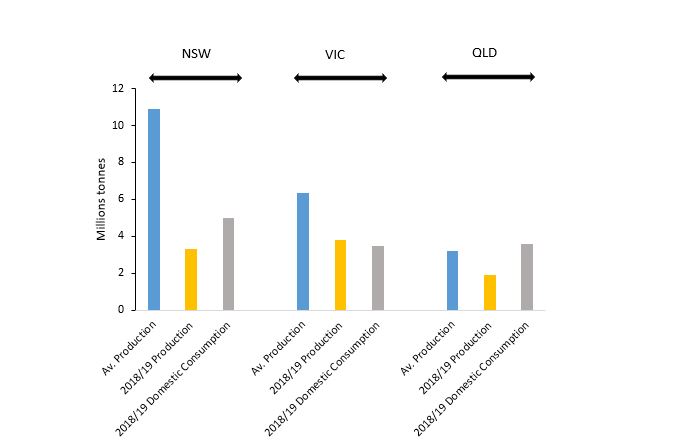

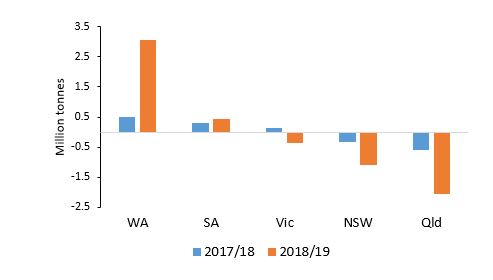

As an illustration of how reduced east coast grain production can affect national grain flows, consider the impact of the 2018 drought in eastern Australia (Figure 2) on grain production, domestic consumption (Figure 3) and grain flows (Figure 4).

Figure 2. Rainfall deficiencies across Australia in 2018 (up until Nov 30) (Source: Bureau of Meteorology).

Figure 3. The impact of the 2018/19 drought: New South Wales (NSW), Queensland (Qld) and Victoria (Vic) became grain importers (Source: Based on data in an appendix in ACCC (2019) Bulk grain ports monitoring report 2018–19, Canberra).

Figure 4. Coastal shipping flows from or into each State in 2017/18 and 2018/19 (Source: Based on data in an appendix in ACCC (2019)).

In 2018/19 some regions in SA were also affected by drought. The SA grain harvest was approximately 5.6mmt, of which the main grain handler and exporter, Glencore, only exported around 2.6mmt, indicating that around 3mmt was either stored, used locally or exported to eastern Australia. Hence, due to SA’s small domestic market, even in low production years, SA can capitalise on favourable market opportunities in eastern Australia.

In years when SA escapes drought, yet NSW and Qld are drought-affected, then sizeable interstate grain flows from SA are likely. Freight differentials in coming decades could be further affected by construction of the inland rail in eastern Australia, due for completion in 2025. If the inland rail is sufficiently cost-effective, then interstate grain flows from SA could be much enhanced in some years. In addition, construction of additional grain port infrastructure in SA will facilitate coastal trade. In eastern Australia, south to north flows of grain by rail, road and ship are likely to become increasingly important towards 2030 as a product of climate volatility and continuing growth in the east coast increase the demand for grain.

The constant challenge of a warming, drying climate is likely to limit crop yield growth in SA and will increase the dependence of extensive livestock production (sheep, cattle, dairy) on supplementary grain feeding. Simultaneously, further population growth in SA and more especially greater population growth in the eastern states of Australia will increase the national market demand for grains, especially feed grains. The corollary is that growth in grain production in SA is likely to be modest and the tendency will be for a growing proportion of SA grain to flow to domestic markets. Exports of SA grain are likely to be constrained by the growth in the Australian domestic market and the constraints of climate trends on crop yields.

Nonetheless, on balance, the SA grains industry mostly will remain focused on grain export, as usually over 85 percent of SA grain production flows to export markets. However, depending on seasonal conditions in eastern Australia, interstate flows of grain strategically will become more important and will add to the volatility of SA grain exports.

In coming decades, SA’s grain supply chains will be affected by the combination of limited growth in crop production and an increased frequency of interstate grain flows. Farmers and grain users are likely to react by increasing their investment in grain storage; especially while interest rates are low which makes affordable the cost of carrying grain across seasons. Easily stored feed grains like lupins and barley, if high-yielding varieties become available, could feature more in farmers’ crop portfolios. Farmers are likely to enlarge their focus on feed grain production and will target, more frequently, domestic market opportunities in eastern Australia and local feed grain value-adding opportunities.

Farmers are likely to have increasing choices over where and when they sell grain, due to the low cost of storing grain (i.e. a low interest rate environment), and the emergence of a range of domestic market opportunities. One other implication is that the case for maintaining the high degree of port access regulation that especially characterises SA’s grains industry will weaken through time.

Conclusion

Relatively modest population growth in SA is expected towards 2030. By contrast, Australia’s population is projected to increase by between 16 and 19 per cent by 2030. This means between 4.07 and 4.89 million additional people, mostly residing in eastern States. Despite this projected increase in population and the associated demand for feed and human consumption grains, little increase in the area sown to crops in Australia is envisaged.

The corollary is that, especially during periods of drought in the eastern States, SA’s grains industry is well poised to benefit from domestic market opportunities in eastern Australia. SA’s proximity to these markets, facilitated by further investment in grain supply chains, will fuel the profitability of SA grain production towards 2030.

References

Kingwell, R., Elliott, P., White, P. and Carter, C. (2016a) Ukraine: An emerging challenge for Australian wheat exports, Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre, April 2016. Available at: Ukraine Supply Chain Full Report - Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre

Kingwell, R., Carter, C., Elliott, P. and White, P. (2016b) Russia’s wheat industry: Implications for Australia, Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre, September 2016. Available at: Russia wheat industry implications for Australia - Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre

Kingwell, R. and White, P. (2018) Argentina’s grains industry: Implications for Australia. Available at: Argentina’s grains industry: Implications for Australia - Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre

Kingwell, R. (2019) Australia’s grain outlook 2030. AEGIC Industry Report. Available at: Australia's Grain Outlook 2030 - Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre

Kingwell, R., Rice, A., Pratley, J., Mayfield, A. and van Rees, H. (2019) Farms and farmers – conservation agriculture amid a changing farm sector. In (Eds. J Pratley and J Kirkegaard) “Australian Agriculture in 2020: From Conservation To Automation” pp33-46 (Agronomy Australia and Charles Sturt University: Wagga Wagga).

Davies, S., Parker, W., Blackwell, P., Isbister, B., Better, G., Gazey, C. and Scanlan, C. (2017) Soil amelioration in Western Australia .Available at: Soil amelioration in Western Australia - GRDC

Contact details

Professor Ross Kingwell

AEGIC

3 Baron-Hay Court, South Perth, WA 6151

08 6168 9920

ross.kingwell@aegic.org,au

Was this page helpful?

YOUR FEEDBACK