Spray application manual

7 June 2025

Module 10: Weather monitoring for spraying operations

10.4 Surface temperature inversions

Published 24 January 2025 | Last updated 20 January 2025

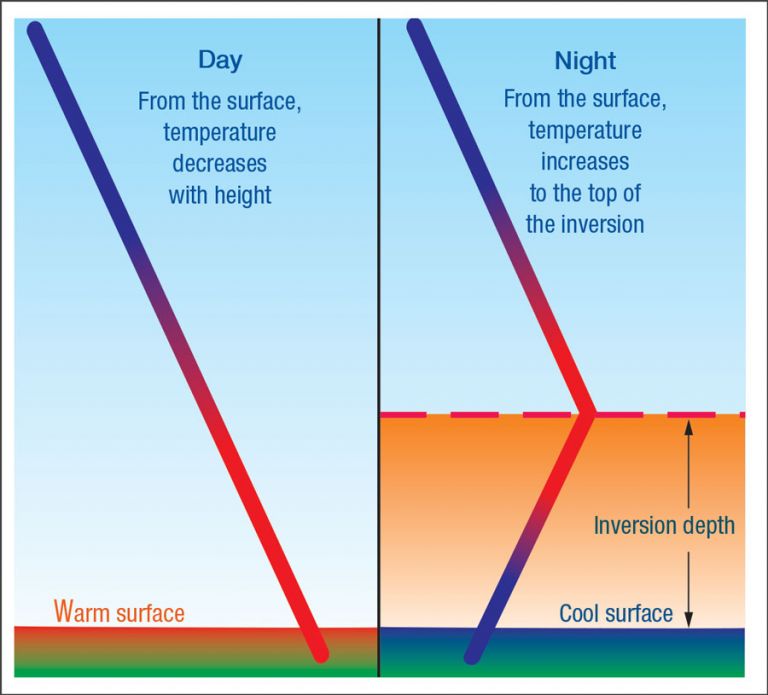

During the day the sun heats the Earth’s surface, which in turn warms the air in contact with the ground. As the distance from the surface increases the air temperature normally reduces.

When an inversion is present the opposite situation exists: A layer of cool air can develop near the ground surface that is cooler than the air immediately above this layer. There are a number of ways an inversion can form, but most often they form from 1-2 hours before sunset as the surface temperature cools, which in turn cools the air in contact with it, so that air temperature appears to increase with height.

Surface temperature inversions may remain in place until 1-2 after sunrise.

Typical vertical temperature profiles for a point in time during the night and day. The day profile typically cools with height and the night profile typically warms with height to a depth that constitutes the surface temperature inversion layer. The point where the temperature stops increasing is the top of the surface temperature inversion layer.

Vertical surface temperatures

When an inversion is present it can block a location from the normal weather pattern (synoptic winds). Once this situation exists, air movement in a particular area is driven by local effects, such as the shape of the landscape and cold air drainage patterns.

The air movement under inversion conditions can be quite different to the normal ‘daytime’ situation, as the air may not mix and move in the same way, which prevents airborne droplets from diluting, or being bought to the surface by turbulence.

Find out more

For more information on surface temperature inversions and monitoring see: Grow Notes Spray Drift

When an inversion occurs close to the ground, it is referred to as a surface temperature inversion. For the purpose of spray decision making, a surface temperature inversion is determined as the vertical temperature difference (VTD) and is measured by subtracting the temperature at 2m above the ground from the temperature at 10m above ground level. If the outcome is positive, a surface temperature inversion is in place.

However, for pesticide application, inversions can be further defined as hazardous or non-hazardous. A non-hazardous inversion occurs where the temperature difference between 2m and 10m indicates an inversion but adequate turbulence remains to ensure atmospheric mixing is still occurring. Identification of non-hazardous inversion conditions requires access to a monitoring station that can measure both temperature at 2 and 10m and turbulence. Product labels typically prohibit spraying when a hazardous surface temperature inversion is present.

From the spray applicator’s perspective, there is no way to determine how far droplets trapped in a hazardous inversion may travel, or where they may land.

DO NOT apply if there are hazardous surface temperature inversion conditions present at the application site during the time of application unless there is a recognised inversion monitoring weather station which aligns with and reflects weather conditions at the site of application, that indicates that the inversion is non-hazardous.

“A surface temperature inversion is likely to be present if:

mist, fog, dew or frost have occurred

smoke or dust hangs in the air and moves sideways, just above the ground surface

cumulus clouds that have built up during the day collapse towards evening

wind speed is constantly less than 11 km/hr in the evening and overnight

cool off-slope breezes develop during the evening and overnight

distant sounds become clearer and easier to hear

aromas become more distinct during the evening than during the day.

When application occurs in an area not covered by recognised inversion monitoring weather stations, all surface temperature inversion conditions are regarded as hazardous.” (Australian Pesticide and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA))

What we do know

What we do know from Australian research is that spraying during hazardous inversion conditions at night, even with reasonable wind speeds, can increase the amount of spray that remains in the air by up to 5 times more than spraying with the same set-up during daylight hours (after the sun has risen above the horizon enough to start heating the ground to cause the air to mix due to turbulence).

Find out more

For more information about identifying inversion conditions, and their impact on spraying, see the factsheet on hazardous inversion.

For more information on weather essentials for pesticide application, refer to the factsheet.

For more information on the meteorological principles influencing pesticide application, refer to the factsheet.

It is possible to determine if a surface temperature inversion exists by measuring the difference in temperature at two different heights, usually at 2 metres and 10 metres. However, this requires very sensitive weather instruments to detect a difference over a relatively short distance, and even if you can measure such a difference, it will not tell you whether it is really safe to spray i.e. is the inversion hazardous or not. To understand if the inversion is ‘hazardous’ will also require measurement of air turbulence.

If we consider the typical change in temperature that can occur with height above the ground, known as the adiabatic lapse rate, there are two common lapse rates quoted in scientific literature, known as the dry lapse rate and the saturated lapse rate.

Adiabatic lapse rate (dry and saturated)

In dry air: the air temperature normally drops by about 1°C per 100 metres (0.1°C over 10 metres, or 0.08°C over 8 metres).

In saturated air: the air temperature normally drops by about 0.6°C over 100 metres (0.06°C over 10 metres and 0.048°C over 8 metres).

For the purpose of this exercise, assume an average value for the lapse rate of about 0.5°C over 100 metres (0.05°C over 10 metres and 0.04°C over 8 metres).

The kinds of temperature sensors required to detect a difference would need to have an accuracy of well below 0.1°C, and ideally about 0.02°C or less.

Such instruments need to be matched for accuracy, and will generally be too expensive for growers or spray applicators to consider. They may also be difficult to maintain, including regular calibration to ensure accuracy.

Warning

Even if you can detect a temperature difference over a relatively small difference in height above the surface, this will not tell you whether it is safe to spray.

In fact, using temperature difference at two heights alone to provide an indication of inversion presence may actually stop an operator spraying when it may be safe to spray (when the amount of turbulence is suitable), and will perhaps encourage spraying when it is not safe (when a lack of turbulence favours droplets remaining airborne).

Determining ‘safe’ spraying conditions must take into account how the air is moving and mixing. This requires accurate measurements of several parameters (not just temperature differences with height) and sophisticated modelling of how the air is moving at a location and over a district.

Until such methods and models have been fully developed and validated, extreme caution needs to be exercised in trying to relate temperature differences over height with safe conditions for spraying.

Recently, technology suitable to determine the presence or absence of a hazardous inversion inversions has become available.

COtL maintain an extensive mesonet of base stations covering large areas of agricultural land across the mid-North, Mallee and Riverland regions of South Australia. https://cotl.com.au/

Across key geographic regions from southern NSW to central Queensland, the WAND network of base stations is operated by GoannaAg via a joint GRDC/CRDC investment. https://www.goannaag.com.au/wand-app

These networks provide users with current weather measurements critical for spray decisions, along with both a current, and two hour future predication of the presence/absence of a hazardous surface inversion.

For applicators to have confidence in the base station data and the applicability to their location they should select the closest location, while also ensuring that there are no substantial topography barriers within direct line of site to the base station.

While base station technology required to provide this level of information is typically expensive to install, calibrate and maintain it is possible for a grower, or group of growers, to invest in their own base station should a suitable network location not be available.

Find out more

For more information Goanna Ag WAND network: https:// www.goannaag. com.au/wand- network

COtL Mesonet: https://cotl.com. au/existing- mesonets.html