Spray application manual

7 June 2025

Module 7: Mixing and decontamination

7.5 Checks for physical compatibility - the jar test

Published 24 January 2025 | Last updated 20 January 2025

A jar test is an easy way to check for physical compatibility of products. It is recommended when unusual product mixes are used, when mixing products for the first time or when substituting brands.

‘Jar test’ results are quick and will provide a good indication of what is likely to happen in the tank.

The ratios of product and water used should mimic the field rates. While it is called a jar test, the best container is an elongated clear glass cylinder (or bottle) with an

appropriate lid or seal capable of holding a minimum volume of 1 litre. Only glass jars or bottles (not food containers) that can be fully decontaminated and cleaned at the end of the process should be used. Appropriate PPE should be used when handling undiluted products.

Mixing conducting a jar test

15 January 2025Mixing - conducting a jar test. Another video from GRDC's Spray Application GROWNOTES™ series.

| Jörg Kitt: Today I'm going to show you how to conduct the jar test. We need only some very simple material like a PT bottle marked up and the syringe which you can easily get in a pharmacy, that's basically what we need. The only thing that needs to be precise is actually the measurements because we really want to mimic what happens when we mix our chemicals in the tank, and I would suggest the easiest is to work on a per hectare basis and divide everything by a hundred. So for example if you use 70 liters per hectare in our jar test we will be using 700 millilitres - 70 litres divided by a hundred. If you use a litre of glyphosate per hectare we will be using 10 millilitre. Ok so let's go through one and I have three chemicals here. I have liquid ammonium sulfate, I have 2,4-D and I have glyphosate, so a very common and standard scenario. So we start off with probably 400 millilitres of water in our bottle, because when you start mixing you probably have only sixty percent of your water right in the tank, and from 700 millilitres just a bit more than the half is 400, so that's what mimics our tank. Ammonium sulfate is measured in per hundred litres rather than per hectare, but it's two litres per one hundred litres so per leader would be a 20 millilitres, but because we're only working on 700 millilitres here I have 40 millilitres of ammonium sulphate in here, which I put in because it's already pre-mixed we don't have to worry about anything, ready to go. The next one is our 2,4-D and we're working on 1 litre so they're 10 millilitres in here. Agitation by hand is very easy to mimic and last not least we're putting our glyphosate in again at 1 litre per hectare, so we're looking at 10 millilitres. So a little bit of a shake and in real life you would be filling up our tank to 100 hundred percent - that's what we're doing here as well, so basically the 700 millilitres i was talking about earlier. That's what we want to achieve now, and here is our full tank and we have mimiced exactly what we would do in our mixing procedure. Now in this case everything worked perfectly and early on I did this one here, this is exactly the same mixture, but I tried to cut corners and took less time, I used less water and as a result we have precipitate on the bottom and the mixture failed. So if you have clogged up filters and the precipitate on the bottom there that's actually what it will do. So simple isn't it? |

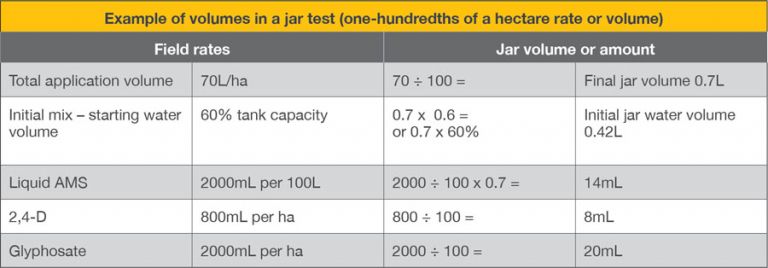

Jar test - water volume

The easiest way to simulate actual tank-mix ratios is to divide everything by 100. For example, 70 litres per hectare (L/ha) becomes a 0.7L volume in the jar. It is a good idea to use the same water source that is going to be used to spray with. If the initial mixing takes place with 60 per cent tank capacity of water, this should be reflected in the jar test as well. For example, 60 per cent of 0.7L would amount to 0.42L (0.7 x 0.6 = 0.42) for the initial volume of water in the jar.

Jar test - product rates

Product rates for the jar test should also use the field rate divided by 100.

For example: a rate of 2L/ha, or 2000 millilitres per hectare (mL/ha) becomes 20mL per test, a rate of 800mL/ha becomes 8mL per test, and so on.

Adjuvants can be a little trickier because they are mixed at a rate per 100L. For example, 2000mL per 100L of water with a liquid AMS becomes 20mL per litre. For a tank mix to be applied at 70L/ha, the total jar test volume would be 0.7L, not a whole litre. The amount of liquid AMS to add to the total jar volume of 0.7L would be 14mL (20mL per litre x 0.7L = 14mL).

It is useful to have some syringes to measure small volumes. They are easily obtained from pharmacies or medical supply shops and come in various sizes; 3mL and 20mL should provide sufficient volume variation. Dry products require scales: a portable scale (electronic balance) should provide reasonable accuracy in the 10 – 20 gram range.

Conducting the jar test

The mixing order should be the same as that used in the field. Shaking the jar after mixing will simulate agitation. When dry products are used they should be fully dissolved before the next product is introduced (this may require a separate container to dissolve dry products, if that is what you do in the field). Waiting for products to fully dissolve may take some time, for example, when using crystalline ammonium sulfate, but this is also what will be required for the actual tank mix.

After the mixing is finished the jar should be left to stand for 5 minutes.

An example of field rates and the rates to be used for a jar test.

Possible results of the jar test

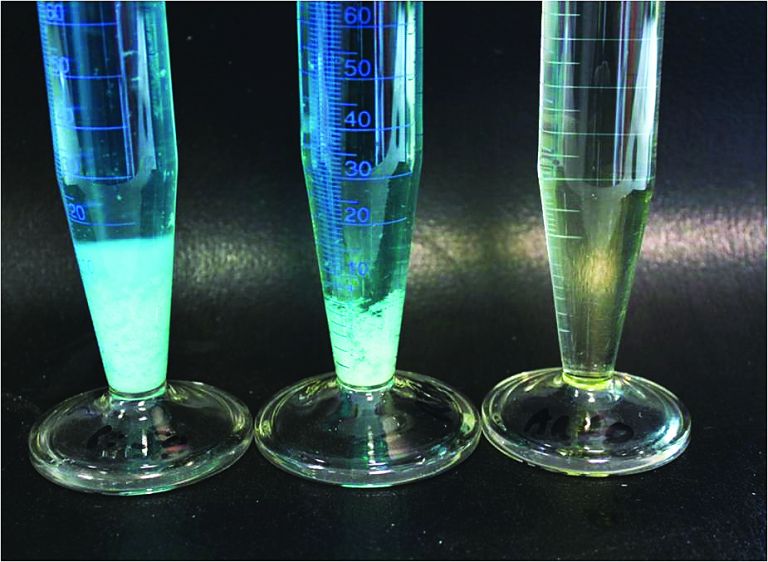

The jar contains a homogenous solution. This is where the whole mixture appears consistent in appearance. This is the best result a jar test can produce. The mixed solution seems to be stable and suggests that the planned tank mix is physically compatible and products will be able to be mixed in the tank (right hand side image below).

The jar contains thick layers or banding in the profile. This indicates that the solution is not stable without agitation. If some shakes of the jar can make the solution homogenous again, and it stays this way for two minutes before layers start to form slowly again, it can be assumed that agitation should overcome the problem (left hand side image below).

However, if the banding returns within about 30 seconds, it is a strong indication that there will be a problem with the tank mix that even good agitation may not be able to overcome.

There is sediment or precipitate on the bottom of the jar. This indicates strongly that the mix is not physically compatible or the mixing procedure was not right, e.g. adding 2,4-D before allowing sufficient time for crystalline ammonium sulfate to dissolve (middle image below).

Three possible outcomes of the jar test: Left – layers forming, middle – sediment produced, right – well mixed.

If there seems to be a problem after several attempts at the jar test, there may be solutions. The mixing process can be made more robust by:

using more water, e.g. the use of almost 100 per cent of the tank volume rather than only 60 per cent as the initial volume of water added to the jar. In the previous example, that would mean to attempt the mix starting with 0.7L in the jar instead of 0.42L;

the use of a more suitable water source could help, e.g. tap or rainwater instead of bore water;

allowing more time for products to disperse before the addition of further products;

using a different brand of the same active ingredient (if available), as a different surfactant system may be used.

A jar test will provide information on physical compatibility only. It will not provide any information on biological compatibility (possible losses or gains in efficacy).